“The coffee shop never hears about the problems. They hear about the 80-bushel canola, but they very seldom hear about the quarter section that was wiped out with blackleg.”

– WELDON NEWTON

Push your crop rotations and you’re pushing your luck.

Nevertheless, a lot of farmers have been tightening their canola rotations and getting away with it thanks to blackleg-resistant and herbicide-tolerant varieties. Before those innovations, weeds and disease forced farmers to limit canola to a one in four-year rotation.

Read Also

Canadian canola prices hinge on rain forecast

Canola markets took a good hit during the week ending July 11, 2025, on the thought that the Canadian crop will yield well despite dry weather.

Saskatchewan-based Agriculture and Agri-Food researchers Stu Brandt and Randy Kutcher have concluded, based on their research, farmers can grow canola one in three years or even one in two, if they plant blackleg-resistant varieties.

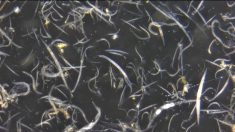

BLACKLEG

But that study also found some fields of resistant canola with 30 per cent blackleg infection. That’s troublesome, says Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives’ oilseed specialist Anastasia Kubinec. The more often canola is grown on the same ground, the more blackleg will build up and the lower the potential yields. Kubinec said she’s already seeing the results.

“There are guys who have been doing it (planting canola every other year) calling and saying they have a really bad blackleg problem,” she said. “Or they’re saying my canola isn’t yielding the same, even though I’m growing the top varieties, what’s going on?”

The earlier blackleg hits a field the more potential loss because the disease can spread with splashing rain.

“A guy can have a nice, big fluffy swath but the seeds can be shrivelled because of blackleg and they fly out the back,” Kubinec said. “Then the farmer wonders why field ‘B’ is only going 30 (bushels an acre) and all his other fields are going 50, even though they all looked the same.”

PROBLEMS

Farmers in the Peace River are well known for their tight canola rotations, but Kubinec said that’s brought on problems with girdling brown root rot. [The problem was worse in rapa (polish) canola.]

Crop rotation was discussed at the Manitoba Agronomists’ Conference at the University of Manitoba Dec. 15. Neepawa-area farmer Weldon Newton said pushing canola rotations is a ticking time bomb.

“The coffee shop never hears about the problems,” he said. “They hear about the 80-bushel canola but

they very seldom hear about the quarter section that was wiped out with blackleg.”

Newton added that farmers who are surrounded by those who push their canola rotations will also suffer because the diseases spread.

Peter Entz, director of seed and traits, for James Richardson International said that’s the case with sclerotinia, but farmers with better rotations will see fewer soil-borne infections in their crops.

“If you do the same old thing over and over again, weeds, herbicides and things like that tend to anticipate that and make your life a little more miserable,” he said.

MULTIPLE FACTORS

There are 35 or more factors to consider when deciding what crops to grow, Entz said later in an interview. Profitability is one, but growers need to consider the short-and long-term impact.

Ken Harms of Ken’s Crop Care in Killarney told the conference often growing canola is a “no-brainer” when it comes to gross revenue. But he said he gets farmers to think about the average total revenue per acre they need, which then allows them to think about growing other crops that might not pay as well, but have an agronomic benefit.

Weeds and weed control also play a big role in what crops get planted, he said.

“If you’re wanting to grow Nexera canola and you’re in the Clearfield system peas are not an option,” he said. “Or if you’re going to grow peas you’d better stay away from Clearfield canola because you’re going to have some volunteer stuff. The same thing with Roundup Ready canola in Roundup Ready soybeans.

“Weed control takes a lot of planning up to four years down the road.”