It has been nearly a century since Foxwarren’s stone soldier began his vigil in this tiny western Manitoba village. The war memorial where he stands bears the names of 15 local young men who died in the Great War of 1914 to 1918.

These stone soldier statues are a familiar sight in Manitoba, and notably southwestern Manitoba, says author of Remembered in Bronze and Stone: Canada’s Great War Memorial Statuary. Alan Livingstone MacLeod has counted 33 of them. He has documented 18 of the 25 he visited while in this province.

Read Also

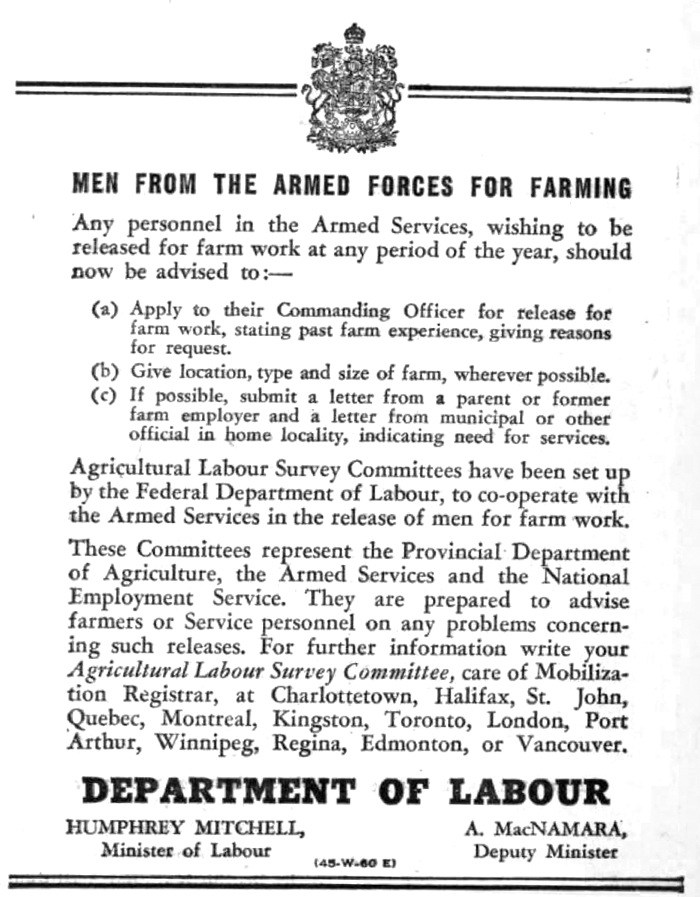

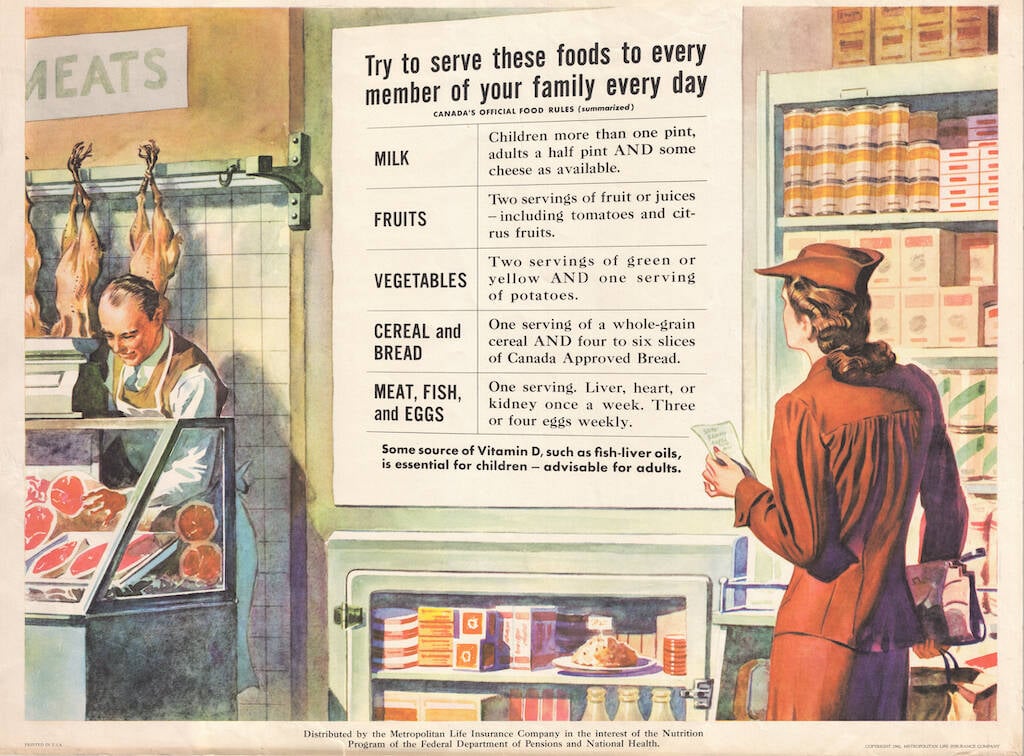

Canada’s ‘Harvest for Victory’ in the Second World War

Propaganda posters celebrating farming show the legacy of Canadian agriculture during the Second World War.

Manitoba, in fact, has one of the highest concentrations of this particular type of war memorial — a single stone soldier — than almost anywhere else in Canada, said Livingstone MacLeod.

“Nova Scotia, by my calculations, has more war memorials featuring the statue of a soldier than any other province per capita-wise,” he said in an interview from his home in Victoria, B.C. “Manitoba must be very close behind.”

And southwestern Manitoba has some most impressive sites, he said.

Foxwarren’s monument is described in detail in his book that features 130 of some 200 of these statues found across Canada.

It meets what he defines as the gold standard of these sites, in that it bears so much information, he said, some- thing that many of the other Manitoba communities also do.

“I’m not sure I can explain it,” Livingstone MacLeod said. “I think there is a higher pro- portion of monuments in small communities, especially in southwestern Manitoba, that meet what I define as the gold standard. You can see all the names of those who fell. We often see how old they were at the time they died. We know what battles they died in and so on.”

Not a single village or town anywhere in the country was left untouched by the catastrophe of the war and communities chose many forms of memorial to honour their fallen after 1918.

Today some 7,500 memorials are found across the country, bearing local names of some of the 60,000 men and women who never returned from the war.

A native Nova Scotian, Livingstone MacLeod was moved to write about these soldier statues after visiting Westville, N.S. in 2010. He went there to see the medals of a beloved great uncle, who fought in and survived the Great War, and whose stories inspired MacLeod’s lifelong interest in Canada’s part in it.

While in Westville, Livingstone MacLeod chanced upon that community’s own remarkable soldier memorial. It was made of bronze. He was tremendously moved by the sight of it, he said.

“It literally stopped me in my tracks,” he said. “It was and still is the community war memorial I consider the finest in Canada.”

It also bore the signature of the artist who created it, which piqued his curiosity so much he decided to learn more about him, and other creators of Canada’s standing soldier war memorials. He began his research and in 2011 he and his wife, Janice, set out on what would be two coast-to-coast trips to visit and document these sites.

What he produced was a first- ever account explaining how communities came to choose these life-size likenesses of a soldier to honour their fallen. It also includes the biographies of the artists who created them and family histories of some of those whom these sites immortalize.

Close to half of these memo- rials are of Carrara marble, carved by anonymous Italian craftsmen. His book explores why so communities made that choice and how it led to similarities among these monuments right across the country; towns such as Canso, N.S., and Oakbank, Man., and Reston, Man., and Tatamagouche, N.S., have very similar war memorials.

But soldier memorials certainly aren’t identical, and certainly neither is their condition, MacLeod notes.

Livingstone MacLeod’s careful inspection of these sites also shows how the passing of time and extreme weather, even neglect and occasional vandalism, is taking its toll. Bronze will endure but not Carrara marble, especially when exposed to the extremes of a Canadian climate, said Livingstone MacLeod, who describes in his book some sites that are a “much-eroded remnant” of what was placed so many years ago.

“White-stone soldiers need to be looked after,” he writes. “Some communities attend vigilantly to the duty; others do not.”

Livingstone MacLeod said several responses to his book have come from readers moved by it to begin attending to this duty once more. “At the very least I’m hoping that in some cases my book will inspire an effort to restore and refurbish the community war memorial in the place where they live,” he said.

Many have also continued to care for these sites very well, he said.

“In fact there are communities in every province that are showing, by the current state of their monument, that they’re doing really great work in pre- serving them,” he said. The tiny village of Margaret, Manitoba is one example, he said.

“Whoever is looking after it is doing a wonderful job,” he said.

“Some communities still care,” he said. “And some appear not to care, not as much as we might wish they did.”

Remembered in Bronze and Stone is published by Heritage House Publishing and sold at bookstores across Canada. It is also available for purchase online at Amazon, Chapters Indigo, and from the publisher.