How many times has this drama played out in farm country?

Son grows up, goes to college, then comes back with newfangled ideas about how to farm.

Son goes to bank, borrows an enormous sum, and buys farm lock, stock and barrel from parents, who in turn, pay a hefty tax bill on the payout.

The banker and the taxman clink their tumblers together, as a new generation of farmers is locked into decades of debt slavery.

Why should farm families pay interest to the banks for the privilege of owning the same piece of land, generation after generation?

Read Also

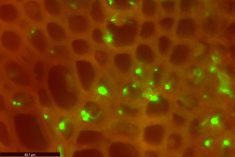

Potato growers beware new PVY strains

Newer strains of potato virus Y (PVY) are creating headaches for potato farms in Eastern Canada, and Manitoba farmers should pay attention

A possible solution to that age-old dilemma was one of the highlights of a panel discussion featuring three young ranchers at the recent Manitoba Grazing School.

Tod Wallace, who works part time as a MAFRI beef extension specialist, returned with an animal and range sciences degree from North Dakota State University in the 1990s, and later bought the farm that has been in his family for over 125 years near Oak Lake.

The deal went down just months before BSE hit in May of 2003.

“I’ve been there and done that,” said Wallace, in response to a question on farm succession regarding the burden of buying land, equipment, and cattle from the older generation.

DIFFERENT APPROACH

His debt is scheduled to be retired in 2019.

“Wow, if we make it, what a load is going to come off,” he said.

“It would have been far easier to pay them a lump sum per year for them to live on for the rest of their life,” said Wallace, who runs 500 head of cattle on 5,000 acres.

“The interest would have been going directly to them, instead of that fine institution that was gracious enough to lend me the money. And that was a pile of dough. Not only that, but for the folks, income tax was definitely a problem for them as well.”

At the time, he added, their consultations with lawyers, accountants and neighbours led them to believe that the full buy-out was the way to go, but now, in hindsight, he said that they would have “definitely” done it differently.

He decided to get an off-farm job last year after figuring out that he was losing $50 on every calf he sold.

“For young farmers, to go out and get that six-figure loan, wow, you have to have the right mindset to sleep at night,” said Wallace. “November 1 and May 1 are two terrible dates in our household.”

A simpler solution would have been to reach a written agreement on an annual payment, say $30,000 per year in perpetuity, that would have served both his family and his parents much better, he added.

Ben Hamm, who also works with MAFRI as a business development specialist, described in a short presentation how in 2002, fresh out of high school, he bought 25 heifers from his dad.

RENT INSTEAD OF OWN

To make ends meet, he worked in a nearby hog barn until 2003, then went to the University of Manitoba to get an animal science degree.

After graduation in 2007, he started working for MAFRI, and currently farms with his dad near Tolstoi, running a 150-head cow-calf operation on 1,440 acres.

He bought three adjacent quarters of land next to the original farm after he realized that their existing land base was not enough to support two families. In retrospect, he said that he should have looked at renting as a cheaper option, or even long-term rent-to-own deals.

He bought land for $300 per acre, but his current land debt amounts to $1,700 per cow, and he’s trying to cut costs by reducing days on feed through extended grazing.

“There is a quarter that we do rent, and we’re barely paying his taxes. You can really get some cheap rents, so you should take a look at what’s available in your area.”

Panellist Gwen Donohoe, who still owns a few dozen cattle on her parents’ 300-head cow-calf and grain farm near The Pas, is working on a PhD in soil science at the University of Manitoba.

She got an agriculture degree, then came home, bought cows and started trying out organic, grass-fed methods and niche marketing.

“I got home with lots of big ideas,” she said. “I took rangeland management, so I told my parents that they were doing everything wrong.”

STILL A STRUGGLE

She started building fences and off-site watering systems, but eventually was forced to give up and head back to school.

“This generation has grown up seeing our parents really struggle the last 10 to 20 years in particular with being able to pay off loans and debt, working 12 hours a day with off-farm jobs just to try to make ends meet,” said Donohoe.

“I totally understand that parents wouldn’t want their kids to take on that kind of stress and responsibility like they did, especially when there are other opportunities for us.”

It is “sad” she said, that in an industry that is the backbone of society, that farm kids, when they say that they want to be a farmer when they grow up, are told by their parents that they should be doctor, lawyer or a policeman instead.

daniel. [email protected]

———

“Itwouldhavebeenfareasiertopaythemalumpsumperyearforthemtoliveonfortherestoftheirlife.”

– TOD WALLACE