Value-added processing can allow Canada to increase its agricultural productivity, but commercialization is still a challenge for innovators, says a group of industry experts.

“Value-added agriculture is probably one of the biggest opportunities Canada’s ever had,” said Frank Hart, interim CEO of Protein Industries Canada.

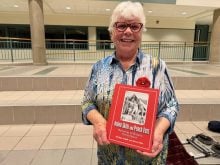

Productivity in Canadian agriculture was a big theme at the Agriculture Enlightened Conference in Winnipeg in November 2024.

Read Also

New Crown-Indigenous partnership to spearhead Churchill expansion

Province announces new Manitoba Crown-Indigenous Corporation to co-ordinate Port of Churchill Plus revamp, bolster northern development and trade

Farm Credit Canada (FCC) economist Craig Klemmer said overall productivity growth in Canada is “largely stalled.”

Agriculture is doing better than other industries on that metric, he added. Still, there has been significant slowing in year-over-year growth in the last two decades, according to the major farm lender.

A 2023 FCC study found that average total factor productivity growth in Canadian agriculture hovered around two per cent year-over-year throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The following decade saw average yearly growth shrink to 1.4 per cent. That number was projected to be about one per cent year-over-year across the 2020s.

Returning productivity to previous peaks could add as much as $30 billion in net cash income over 10 years, the FCC report said.

Klemmer defined total factor productivity as the “combined effects of new technologies, efficiency improvements in economies of scale coming together to define how we’re doing more with less.”

Canadian agricultural productivity has grown through improved farm management practices and economies of scale, he said. Adoption of new technology is big opportunity for growth.

Hart suggested that value-added processing sets the stage for greater productivity, and noted that processing capacity is already increasing in Western Canada. However, Canada needs to move quickly. Other countries are also moving into the processing space.

The Canadian pulse sector has historically relied on moving bulk commodities to developing countries, said Julianne Curran, Pulse Canada’s vice-president of market innovation. Those markets are particularly sensitive to price and political tensions.

“We’re, you know, increasingly at risk for losing markets or losing access to those markets that we still rely heavily on,” Curran said.

Growth in value-added processing is important for the pulse industry’s long-term prosperity and sustainability, she added.

Challenges

Hart warned that innovation isn’t enough to realize success. It’s one of the reasons Protein Industries Canada has started putting more focus on supporting commercialization.

Hart estimated that 60 per cent of companies in Protein Industries Canada’s portfolio are in the process of commercializing their products. Access to capital, market access and the cost of building in Canada are barriers, he said, and Canada needs tax credits to draw investors and funds that can provide large amounts of capital to these companies.

The Canadian regulatory system is also too slow, Hart said. It’s faster to get approval in the U.S. and, if countries plan to market their product there anyway, they may decide to build across the border.

The pulse sector also struggles to find high-volume demand for ingredients amid variability in the supply chain, Curran said.

Pulse Canada is focused on building demand, distinguishing pulse ingredients from other competing ingredients and working through challenges of flavour, performance and standardization, she noted.