“Structure determines process, process determines results.”

– ROY ATKINSON

If there’s a constant with the National Farmers Union, it’s consistency. Canada’s only national, voluntary, direct-membership general farm organization, which holds its 40th annual meeting in Ottawa this week, sticks to its principles.

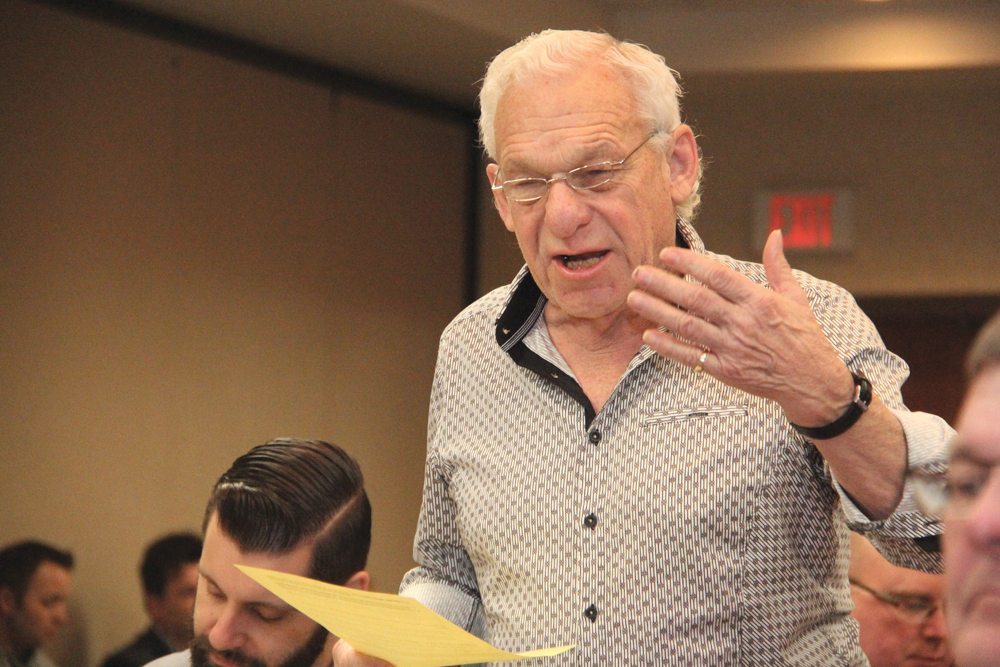

“The first person who compromises, loses,” Roy Atkinson, the NFU’s first president, said in a recent interview from his home in Saskatoon.

Isn’t there a risk of losing everything without compromise?

Read Also

EU’s pesticide reciprocity could disrupt trade

The Canada Grains Council says the EU’s pesticide reciprocity rules could seriously damage trade to one of Canada’s top diversification markets.

“No, once you compromise you’re off track,” said Atkinson, a member of the Order of Canada. “Structure determines process, process determines results.”

The NFU was founded in July 1969 when more than 2,000 farmers from across the country met at the Highlander Curling Club in Winnipeg.

Stuart Thiesson, a staff member with the Saskatchewan Farmers Union, was there but doesn’t recall much about the debate. As an administrator he was beavering away in a back room. Thiesson, who went on to become the NFU’s executive director until he retired in 1992, said many of the issues then were similar to those of today: markets and prices.

Provincial farmers’ unions from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Ontario and British Columbia, with support from farmers from the Maritimes, endorsed the formation of a national union. The Alberta farmers’ union opposed the idea and joined with Alberta’s co-operatives to form Unifarm, which no longer exists. But some Alberta farmers organized locals and joined the NFU.

The provincial farmers’ unions had a national council, but Thiesson said they learned that most issues were national and international and believed farmers would be better served by a pan-Canadian organization.

Bringing farmers of different commodities, from different regions together gives the NFU a “big picture,” Thiesson said.

“Grain farmers in Saskatchewan would support potato farmers in the Maritimes and vice versa,” he said. “That was part of the strength of the union. It was able to see the problems other farmers had in other provinces and try to reach a common policy.”

CATALYST

The NFU is the only farm organization incorporated through an Act of Parliament (June 11, 1970). Then as now the NFU’s goal is to, in a non-partisan way, development economic and social policies that will maintain the family farm as the primary unit of food production in Canada.

The NFU sees orderly marketing – supply management and the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) – as essential tools to that end. Atkinson said the NFU was a catalyst in getting governments to implement supply management.

Whether the times, or the leader, or a bit of both, in the early days the NFU was militant, often organizing demonstrations and rallies. At an NFU highway blockade in Prince Edward Island Aug. 21, 1971 Atkinson was arrested.

“One RCMP constable on each side of Roy, cradled his arms leading to the RCMP cruiser,” wrote NFU member Urban Laughlin, who was part of the demonstration. “Roy shook himself with one officer going in each direction, ‘I can walk,’ he said, which he did on his own.”

During the previous eight days the NFU used tractors to block P. E. I. highways, disrupting traffic.

P. E. I.’s premier soon met with NFU leaders and agreed to some of its demands. The charges against Atkinson were dismissed in court.

The NFU still organizes demonstrations, but not like the old days. There are fewer farmers, many have off-farm jobs and everyone seems busier.

Some argue the trade union tactics hurt the NFU’s image. Many farmers see themselves as businesspeople, not members of the proletariat.

LOST

The NFU fought hard but couldn’t save the Crow rate that gave Prairie grain farmers a break on rail freight rates. But the NFU claims delaying it saved grain farmers millions of dollars.

The NFU opposed Plant Breeders’ Rights and the patenting of genes used in genetically modified organisms (GMO), but lost those battles too.

But the NFU won some too. It was part of a class-action lawsuit that succeeded in getting compensation for P. E. I. potato farmers hurt by Ottawa’s handling of PYVn, a potato disease.

The NFU opposed the introduction of recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH) to bolster milk production, and the Canadian government didn’t approve it.

The NFU also helped organize a major coalition of farm and environmental groups against the introduction of GM wheat, which remains on the shelf.

These days the NFU is drawing attention to Canada’s livestock sector. Based on its research, the NFU concludes cattle prices are depressed because there’s insufficient competition among processors.

The NFU is also warning changes to Canada’s registration system for crops will give seed companies even more control and further constrain farmers’ right to save and grow their own seed.

The NFU also has a knack for being prescient. It predicted reforming the statutory Crow rate would end in its demise. It warned without market acceptance GM crops would disrupt trade. It has been decrying the abandonment of producer car sidings – a hot topic in recent weeks – since 2001.

“You don’t get too much satisfaction out of that, particularly when things happen that you don’t want to happen,” Thiesson said.

BACKBONE

A “key” disappointment for outgoing president Stewart Wells, who was acclaimed to the post in 2001, is that NFU membership isn’t higher. He said he knows thousands of Canadian farmers agree with NFU policies, yet don’t take out a $150 annual membership.

But Wells, who farms at Swift Current, Sask., takes comfort in that the NFU’s membership has grown seven years in a row to more than 6,600, even though the total number of farmers declined.

Much of the increase in membership comes from mandatory farm membership checkoffs in Ontario, P. E. I. and New Brunswick.

Wells says farmers need a farm organization that will stand up to government and not be intimidated.

Wayne Easter, a federal MP and NFU president from 1982 to 1993, gives the NFU credit for having backbone.

“They haven’t been trapped into the bureaucratic culture and they have stood by their principles for standing up for farmers regardless of the political costs,” he said.

As for the future, Thiesson said, the NFU will be around as long as farmers want it to be. The NFU, he said, has outlived most previous farm organizations by at least 20 years. [email protected]