If you missed my last article, we looked at how precipitation forms in warm clouds, after all it is the middle of summer. With the warm summer temperatures one might assume that most of our precipitation would come from warm clouds at this time of year, but in reality, most of our summertime precipitation comes from thunderstorms, which primarily consist of cold clouds. We’ll now take a look at what cold clouds and how precipitation forms in them.

Read Also

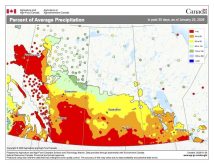

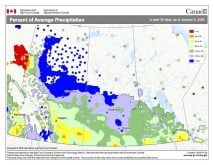

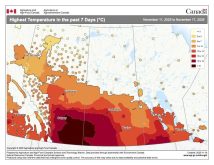

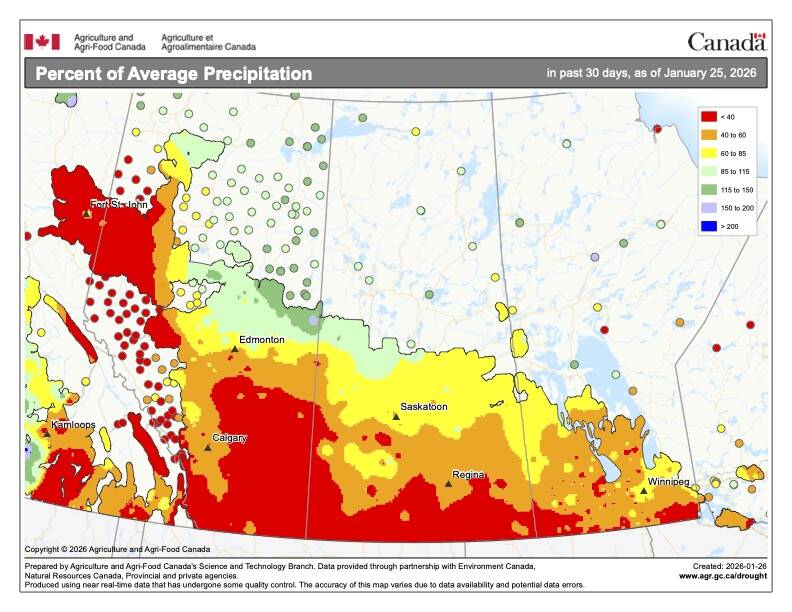

What’s the weather for last half of winter 2025-2026?

A last look at 2025 temperature and precipitation on the Prairies, plus what weather forecasters expect through to spring 2026.

Just what is a cold cloud? A general definition is any cloud that has at least some part of it that is below the freezing point. Here in agricultural Manitoba this cloud dominates our weather for most of the year. Even in the summer, a fair number of precipitation forming clouds fall into this category.

Before we look at the precipitation process in cold clouds we need to explore the idea of super-cooled water. All of us at some point have experienced freezing rain. Under most occurrences of freezing rain we find temperatures just slightly below zero. This means that the surfaces the raindrops are falling on and freezing to are just a little below zero.

Now, if you have ever dropped some cold water onto a freezing surface you would notice that the water does not freeze instantaneously (unless the surface is very cold). So, why then, does the raindrop falling from the sky freeze as soon as it hits a solid surface? Because that falling raindrop was super cooled — the liquid water in the raindrop is actually below the freezing point.

How is this possible? Well, we all learned that water behaves differently than most other substances on earth. While other substances are most dense when they become solid, water is most dense at 4 C. If water didn’t behave in this way we wouldn’t be here. Just think what would happen to rivers, lakes, and oceans if ice were heavier than water. Well, the uniqueness of water doesn’t end there. Strangely enough, when we are looking at water in the atmosphere it doesn’t normally freeze at 0 C.

Just like water droplets need something to condense onto, for water to freeze, the ice crystals need something to freeze onto. The problem that arises is that in the atmosphere there are large numbers of particles for water to condense onto (condensation nuclei) but very few particles for water to freeze onto (ice nuclei).

For ice to form (at temperatures just below zero) you need a six-sided structure, and there are not many of these around. Ice crystals themselves are six-sided, but where do you get the ice crystal in the first place? Because of this, if the cloud temperature is warmer than -4 C, the cloud will be made up of super-cooled water. If we cool the cloud down to around -10 C, ice crystals will begin to form even if there are no ice nuclei, so at these temperatures the cloud will consist of a mixture of ice crystals and super-cooled water. Once temperatures fall to -30 C the cloud will consist almost entirely of ice crystals, and if we are colder than -40 C the entire cloud will be made up of ice crystals.

So now we know that within cold clouds we will usually have a combination of ice crystals and super-cooled water, this is the first step in our process of creating precipitation in cold clouds. Onto the second step — the Bergeron process. The Bergeron process relies on another unique property of water, and that is, if there is just enough water vapour in the air to keep a super-cooled water droplet from evaporating, then there is more than enough water vapour in the air for an ice crystal to grow larger. Because the saturation vapour pressure over ice is lower than that over water, ice crystals will attract water vapour more readily than water droplets will.

Our cold cloud now has ice crystals in it and these ice crystals are growing. As the crystals grow they pull water vapour from the atmosphere. As the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere drops, our super-cooled droplets will begin to evaporate to help make up the difference. These droplets evaporate and the ice crystals continue to grow at the expense of the super-cooled water droplets. After a while, the cloud consists mostly of ice crystals. This process by itself would only result in light amounts of precipitation though, for heavier precipitation we need a third process to kick in. In a cold cloud we call this third process riming and aggregation.

If you recall, in warm clouds rain develops through a process known as collision and coalescence, where water droplets collide and grow together until they are big enough to fall to the ground. In a cold cloud we call a similar process riming and aggregation and it produces a similar result — ice crystals large enough to fall to the ground.

Within cold clouds ice crystals fall and collide into either super-cooled water and grow larger (riming), or they collide into other ice crystals and grow larger (aggregation). Aggregation occurs best when cloud temperatures are only slightly below zero, as the warmer temperatures allow the ice crystals to have a wet surface which helps other ice crystals stick to them. This is one of the reasons we see large snowflakes when it is relatively warm.

Of course, in the summer, when our lower atmosphere and surface temperatures are warm/hot, the ice crystals melt on the way down and fall as rain. As you can see, most of our precipitation, even in summer, comes from cold clouds courtesy of the Bergeron process and the processes of riming and aggregation.

Next time we’ll continue our look at clouds by examining the different types of clouds and how they are named and classified.