As Manitoba farmers wrap up seeding they face more uncertainty than usual, including the potential unravelling of the international, rules-based trading system that has become almost as essential as rain.

Meanwhile, crop prices are down after a decade of relatively good returns spurring global production to exceed demand, exacerbated now by African swine fever decimating China’s hog herd.

Making it worse, after 25 years of increasing trade liberalism, protectionism is on the rise — exemplified by the expanding United States-China trade war and linked to China’s de facto boycott of Canadian canola seed, and all but dried up soybean purchases.

Read Also

The sneak peek of Manitoba Ag Days 2026

Canada’s largest indoor farm show, Manitoba Ag Days, returns to Brandon’s Keystone Centre Jan. 20-22, 2026. Here’s what to expect this year.

As a result, MarketsFarms is forecasting a 100 per cent increase in Canadian canola ending stocks when the current crop year ends July 31.

Because of the trade war the U.S. is subsidizing its crop producers, further distorting world markets and undercutting Canadian farmers’ competitiveness.

It raises the spectre of the mid-1980s when surplus world grain stocks and the U.S.-European Union grain subsidy war depressed world grain prices for a decade. That, and other factors, including high interest rates, forced many western Canadian crop producers to quit. Land values started to fall, cutting farmers’ net worth, triggering a downward spiral pushing thousands off the land.

“I am not looking at things optimistically today — maybe it’s just the day — but I do see those who are raising the ’80s and early ’90s as examples and there are a lot of indicators that we’re sort of on the edge of going in that direction,” Cereals Canada president Cam Dahl said in an interview May 16.

“Again if you look back to the ’80s it wasn’t a good time for farmers. Someone asked me the other day if farmers should be concerned, and yes, farmers should be concerned.”

Ironically, last year the value of Canada’s agri-food exports hit a new record at $59.3 billion.

There could be a silver lining though — short-term pain for long-term gain, — says Mike Gifford, former chief agricultural trade negotiator for Canada.

“The Americans have deliberately created a (trade) crisis (as they did with the EU in the mid-1980s grain subsidy war) in order to force change in China and to also force change in the WTO (World Trade Organization),” Gifford said in an interview May 7.

“If there’s a failure in the Chinese-U.S. negotiation then you could be in for a real rocky ride with retaliation and counter-retaliation. If the China-U.S. deal was primarily preferential… then you could be concerned that this would have the effect of unravelling the multilateral trading system… ”

There’s a sense of deja vu, says University of Saskatchewan agricultural economist Richard Gray. The U.S.-China trade dispute isn’t helping, but the real problem is supply exceeding demand, he said in an interview May 15.

“If one set of countries puts a set of tariffs on the other it’s not a big deal, but if there’s too much grain in the world the whole price regime comes down and that’s where we’re at,” Gray said. “That’s where we were in the ’80s and early ’90s as well.”

A whole new generation of farmers hasn’t experienced tough times, especially those farming since 2006 when world grain prices began to take off, mainly because billions of bushels of primarily American corn was being made into ethanol, University of Manitoba agricultural economist Derek Brewin said in an interview May 16.

“The only thing they saw was the positive,” he said.

Normally the cure for low prices, is low prices. Farmers produce less, or sell more and as supply and demand become more balanced prices rise. But the U.S.-China trade dispute and other non-tariff trade barriers, muddy the waters, distorting market signals adding uncertainty and risk.

“It’s the trade dispute that’s causing new risk (to farmers),” Brewin said.

“It makes things significantly worse.”

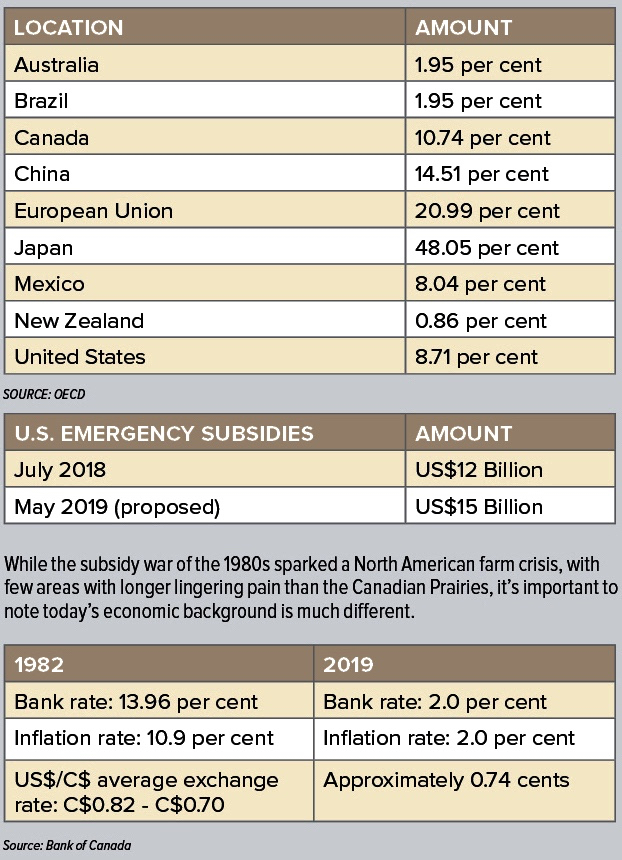

Last year U.S. President Donald Trump created a $12-billion commodity-specific subsidy program to compensate American farmers for lower prices due to import tariffs China placed on American crops in retaliation for tariffs Trump put on imports of Chinese goods. Of the estimated $9.6 billion (all figures U.S. dollars) paid out, an estimated $7.7 billion, or $1.65 a bushel, went to American soybean farmers.

That makes it harder for Canadian soybean growers to compete.

Trump says the program will run again this year.

“If it’s $1.65 for every bushel they produce then they are not going to reduce their production,” Gray said. “I think it really matters for their production levels. Once this stuff is produced and sitting on the market it’s going to continue to have an impact on price regardless whether it’s the export market or domestic market.”

Even more concerning is Trump’s musing that the U.S. government will buy surplus American grain production and donate it as food aid — something that’s illegal under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

Such action is not only tantamount to an export subsidy — also illegal because of how it distorts world prices — but it can destroy local markets making countries even more food insecure by driving subsistence farmers out of business.

Despite the dire outlook, Dahl says Canadian farmers have some advantages.

“If you look right now at the financial stability of grain farmers here and in the U.S. we’re actually in a lot better shape,” he said. “Part of that, of course, is the exchange rate (lower Canadian dollar). But another part of it is our diversity of cropping options. Canadian farmers have been getting market signals and we have a much more diversified crop base and that’a very good thing.”

Arguably it’s a holdover from the 1980s when western Canadian farmers were desperate to find alternative crops, less affected by the subsidy war.

Making matters worse, the United States Department of Agriculture expects global wheat production in 2019 to hit a record of 777 million tonnes.

Most of that wheat will be “middle protein,” Dahl said.

“That distinction is important because we have something a little bit different in CWRS (Canada Western Red Spring wheat) and we’re going on to the world market with a major class that is differentiated from a lot of that,” he said. “Again, that’s a big advantage.”

The fog of (trade) wars

Not all agriculture subsidies are created equal — some can be downright deadly

As a new subsidy war looms, keep in mind agriculture subsidies have always been part of the economic picture for the sector.

They become problematic when governments stop using them for policy goals, like smoothing out the highs and lows of the market, and instead use them as political tools.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. and European Union were locked in a bitter fight to clear a global grain backlog that saw both subsidize exports, placing Canadian farmers squarely in the middle.

In the end the battle contributed to the transformation of GATT (the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs) into the World Trade Organization, and the curtailment, if not elimination, of export subsidies.

However, subsidies that didn’t encourage overproduction for the export market still remained.