The new Canada’s Food Guide and its new emphasis on plant proteins drew swift but measured response from agricultural groups and organizations across the country last week.

In a news release after the guide’s rollout January 22, Ron Bonnett, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA) said it was “unfortunate that the revised food guide does not specifically promote Canadian agri-food as part of its core recommendations.”

“However, the diversity of foods outlined in the food guide are all agri-food products that Canadian farmers grow and produce daily,” he also said.

Read Also

Potato growers beware new PVY strains

Newer strains of potato virus Y (PVY) are creating headaches for potato farms in Eastern Canada, and Manitoba farmers should pay attention

Gone are the famous four food groups, replaced with dietary guidelines, a focus on eating whole foods instead of nutrients, and a key message to eat a diet of mainly plant-based foods.

However, the new guide, which represents its most dramatic overhaul since the late 1970s, also isn’t telling Canadians to stop drinking milk or eating meat.

As widely expected, milk and meat now share a protein category that also includes legumes, nuts, seeds, tofu, fortified soy beverage, fish, shellfish, and eggs.

Why it matters: The Canada’s Food Guide is a highly influential document that informs individual food choices and food policy.

“While the food guide has changed, milk products continue to play a valuable role in helping Canadians make healthy eating decisions on a daily basis,” said Isabelle Neiderer, director of nutrition and research at Dairy Farmers of Canada in a release.

Likewise the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association noted that red meat, such as beef, is “rightfully acknowledged as a nutrient-rich and healthy protein in the new food guide.”

Egg Farmers of Canada points out the new guide continues to recommend eating eggs and reconfirms eggs as an affordable and versatile protein source.

The meat industry ceased the day to remind Canadians that there are nutrients in every bite of meat such as iron, zinc and the vitamin B12 — nutrients not as easily accessed from plant-based proteins.

“It is important to note that plant and animal proteins are not equivalent. Each has a unique nutrient package,” said Mary Ann Binnie, manager of nutrition and industry relations with the Canadian Pork Council.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for a commodity sure to gain from a shift in Canadians’ eating patterns toward more plant-based proteins wasn’t talking in terms of winners or losers.

His take on the new guide is that it offers a more flexible, less prescriptive message than the previous with its recommended servings of specific foods.

“Everyone recognizes that a proper diet has diversity in it,” said Gordon Bacon, CEO of Pulse Canada.

“Certain foods bring certain things to the table. That’s what the guide is recommending.”

Canada’s Food Guide is also now more akin to guides found around the world, but what it hasn’t done, unlike some elsewhere, is link diet and health together with environmental sustainability. We need to start to consider human health and the health of the environment together, no matter what industry we represent, he said.

“I think if we’re going to be asking ourselves about how we’ll meet environmental targets such as the Paris Climate Change Accord, the question has to be, how will we approach it from the food sector?” he said.

“And we’re nowhere close to giving consumers information about how to make choices that are right for them, in terms of environmental sustainability.”

Canada’s new food guide also came out just days after an international report published in the medical journal Lancet that sets the first scientific targets for a healthy diet in the context of the planet’s limitations for food production.

Bacon said he doesn’t expect it will be the Canada’s Food Guide that changes the food industry over the next decade.

“It’s going to be the focus on environmental sustainability and brands, and consumers who want certain brands that will deliver more than tasty food, more than nutritious food, but food that makes a difference from a sustainability perspective,” he said.

A red flag raised by the beef industry last week was that in urging consumption of more plant-based proteins over animal sources of protein, Health Canada missed an opportunity to inform Canadians of the benefits of eating lean beef as a protein source.

“It would be unfortunate if Canadians interpret this bias toward plant-based proteins as a signal to remove red meat from their diets,” the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association said in a news release.

Reynold Bergen, scientific director for the Beef Cattle Research Association, said the environmental benefits of raising beef need to be better understood because beef is the “ultimate plant-based protein.”

It’s highly nutritious protein and it also comes out of production systems maintaining grassland ecosystems that benefit pollinators and have root systems that sequester carbon.

“If we as a society want to continue to grow food and at the same time support these natural environments, consuming beef is a really good way to do that,” he said.

“If we can support a healthy beef industry it’ll support the maintenance of those healthy grassland ecosystems rather than seeing the rest of them converted into unsustainable crop production, frankly,” he said.

Meanwhile, advocacy organizations wanting to see healthy food made accessible to all Canadians say while the new food guide “lays the basis for a healthier next generation,” Canada must start getting serious about offering school food programs across the country.

“With its emphasis on food skills and creating healthier food environments, this is a key moment to establish a national cost-shared school food program,” said Debbie Field, national co-ordinator of the Coalition for Healthy School Food.

“Without an investment from the federal government in healthy school food, it will not have its intended impact,” she said.

Food Guide controversies

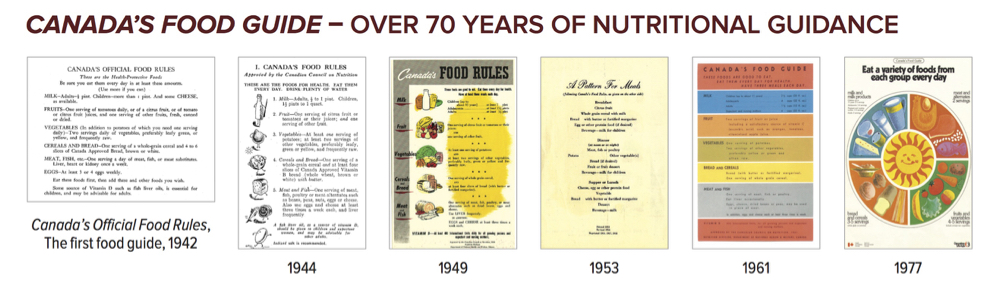

CBC recently reported on the ongoing political nature of the Canada’s Food Guide, noting that during its more than 70-year history the document, in its various incarnations, has always been “about more than nutrition and health.”

- Canada’s Official Food Rules debuted in 1942 and reflected wartime realities. It was in response to widespread malnutrition that saw more than 43 per cent of the first 50,000 recruits rejected for health reasons. It aimed to preserve certain foods for the war effort and encourage consumption of other products.

- The 1944 edition became simply Canada’s Food Rules and paid more heed to nutritional science but critics also noted that it was beginning to mirror the economic interests of Canadian agricultural producers.

- The 1949 food rules were similar to the previous version, but for the first time included warnings about the risks of overconsumption.

- The 1961 edition saw the debut of the Canada’s Food Guide title but the basic guidance remained unchanged from the 1949 edition.

- The 1977 and 1982 editions saw some minor adjustments and a new emphasis on graphic presentation of the information, but also remained familiar.

- The 1992 food guide represented a substantial departure from the past with a new “total diet approach” that aimed to meet both energy and nutrient requirements. The changes proved controversial with the food industry that decried its “good food/bad food” approach.

- The most recent version came in 2007, and controversy surrounding the makeup of a food guide advisory committee, with four of 12 members from the food industry, helped spur the current model with less industry input and more emphasis on nutritional science and healthy lifestyles.