There weren’t a lot of surprises in the June 27 seeded acreage report from Statistics Canada. However, the decisions behind what producers plant as well as the long-term acreage trends are intriguing.

StatCan seeded acreages for most crops were not too far from grain trade expectations.

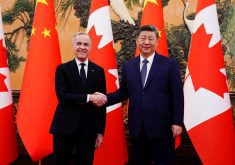

One exception may have been barley, down nearly 13 per cent compared to last year. The drop was greatest in Saskatchewan — down 17.5 per cent. The loss of China as a barley customer and U.S. corn moving north into Canada has really hurt barley price prospects, and producers have responded by reducing acreage.

Read Also

Canadian government got it wrong on public plant breeding

Cuts to Agriculture and AgriFood Canada will undermine Canadian agricultural productivity, says National Farmers’ Union member Dean Harder.

Meanwhile, the national acreage for oats was up by nearly 15 per cent. In Saskatchewan, the largest oat-producing province, planting rose by more than 22 per cent. This, however, is deceiving. Oats still haven’t recovered from the 35 per cent acreage drop that occurred in 2023.

It’s interesting how producers in different provinces make different cropping choices. According to Statistics Canada, Saskatchewan’s canola acreage is down by 2.5 per cent. Meanwhile, Alberta’s canola acreage is up marginally and Manitoba’s canola acreage is up 6.6 per cent from last year.

I suspect some Manitoba farmers are growing more canola to replace soybeans in their rotation. Manitoba’s soybean acreage is down 10.6 per cent. Nationally, soybean acreage is up two per cent because Ontario and Quebec are growing more. Ontario farmers apparently opted for more soybeans while growing less corn.

Another province-to-province anomaly is with mustard. Saskatchewan’s mustard acreage is down 11.6 per cent, with Alberta’s much smaller mustard acreage up by 17.4 per cent. While Saskatchewan grows brown, yellow and oriental mustard, the vast majority of Alberta’s mustard is the yellow type.

Here’s another anomaly: Field pea acreage increased 8.7 per cent in Saskatchewan this year while Alberta’s area fell 1.4 per cent.

Chickpeas, although a relatively minor crop, continue to see more acres in recent years, with most of those in Saskatchewan. In 2023, the chickpea acreage increase was 35 per cent and this year it has increased by another 44 per cent to a total of 454,000 acres. Some producers are turning to chickpeas to get away from root rot problems in lentils and field peas.

Chickpeas hit a million acres more than 20 years ago. Then ascochyta blight and poor prices caused acreage to plummet. Perhaps the increase this time is sustainable. Wet weather can cause severe disease pressure in chickpeas, but fungicides are much better now and producers are less hesitant to use them.

There’s very little good news for flax. The crop’s acreage continues to crash. The crop was down nearly 22 per cent last year and is down another 15 per cent this year. As recently as 2021, Canada had more than a million acres of flax. Now at only 518,000 acres, flax has become a minor acreage crop. Little wonder the Saskatchewan Flax Development Commission had to merge with SaskCanola.

Lentil acreage is up nearly 15 per cent this year. When you delve deeper into the numbers, much of the increase is coming from large green and small green lentils rather than reds, even though reds still dominate. That’s purely economics, with green lentils having much more attractive pricing.

Price prospects can change, and that’s certainly the case with durum, which has seen a significant slip in value. If producers could have anticipated the market softening, perhaps there wouldn’t have been a 5.5 per cent increase in this year’s durum acreage.