It’s tough being a farmer today and it is easy to be fixed on sky watching, that proverbial hope of rain or snow and even perhaps a wee bit of wind.

Even as the farmer watches, there are political and social expectations that we, the keepers of the land, do something to change the course of nature. It is an absurd conversation. How can anyone change the sun and stars, moon and waves, rain and snow, heat and harvests?

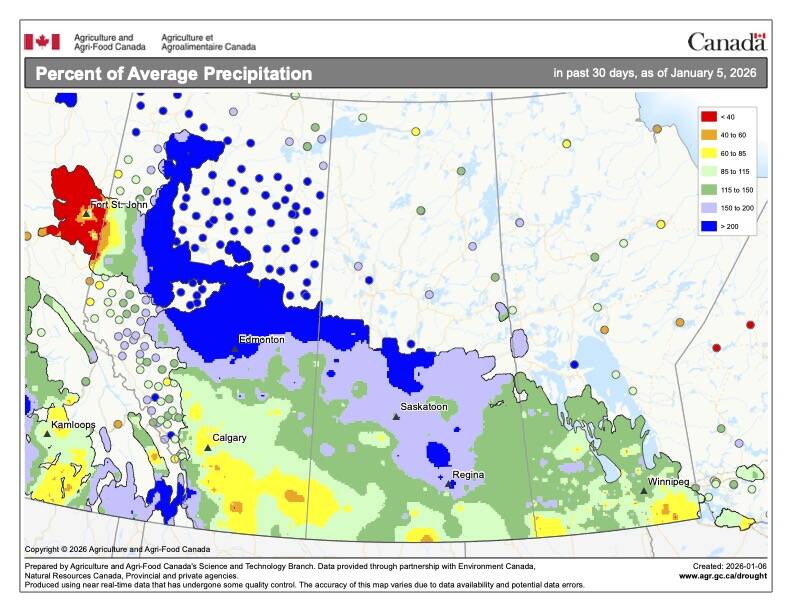

To prepare for this column, I went through 124 years of drought maps to see if what we experience today is reflective of what farmers experienced in the past. In the past 124 years, there have been 36 severe drought years in the United States. Perhaps the most astounding in terms of reach – for drought is often isolated to an area within a nation — was 1954 and 2021.

Read Also

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

Canadians have endured 12 major droughts in the past 124 years that correlate closely with the American periods, especially in the years 1910-11, 1914–15, 1917–20, 1928–30, 1931–32, 1936–38, 1948–51, 1960–62, 1988–89, 2001–03, as well as 2014–15 and 2021-22.

There is a definite pattern but the severity of the weather changed in 2002 when the dry areas lost their historic boundaries and covered larger territory. Looking at weather patterns begs the question: Are we in climate change or patterns of climate normal, and if in change, who is to be held responsible?

It took 80 years for the global livestock population to double (1900–1980) and it has now been declining steadily since 2015 and continues to do so in Canada. The cows aren’t responsible.

Arable area in Canada has been in decline since its peak in 1986 and new land is not found; rather the number of arable acres is supported by a reduction in summerfallow. Weather woe is not caused by farmers creating new fields. Canada has lost more than 15,000,000 acres to urban development and in Ontario alone, over 320 acres are lost to housing and industry every single day.

Urban encroachment paves valuable farming land and disrupts natural waterways, watersheds, and Earth’s diverse storage capabilities. The soil heats. Lack of natural shade and the loss of plants that filter, store and cleanse our earth and air becomes apparent. They have been replaced by stripped mountainsides, hot black roofs, concrete slabs and resource-guzzling industry that radiate and pollute.

In this vast nation, everyone is on the move. It is not the 27,000 seasonal tractors that contribute to climate concerns. It is the 26 million motor vehicles.

Tornados strike fear in the hearts of many and there is a belief that this is new, but they are as common as a garden weed and have been recorded in Canada since 1836, primarily in southern Quebec and Ontario, parts of B.C. and the Prairies.

These catastrophic events happen, but rarely. They were more common in the 1980s, and then settled into an unpredictable but less eventful pattern. Like earthquakes, which were first reported in 1663 and are a regularly occurring event, especially in the Charlevoix region of southern Quebec, Baffin Bay and the west coast, we do not cause these events. They simply are and always have been.

From record freezing at -63 C in 1947 to massive fires, Canada has a long history of both, and has forest fire data dating to 1921. On a time map it is clear that major events covered the nation throughout the last 100 years, although 2023 was the record breaker in terms of total area affected in a single fire season.

Again, looking at historical maps, one can see the shift in consumed territory in 2002 – the same time drought manifested itself more broadly on the continent. 2002 was also the year of contrasts and extremes for weather in Canada.

From the global lens, it is evident on an active timeline map that those countries burning to create open land, such as south Asia, central Africa and South America, are constantly in flame, season after season, year after year. It is important to differentiate this in our conversation.

Weather reporting is currently filled with a touch of sensationalism that drives fear. It is difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff – to know what is true within the context of history.

Our children and our society are as exhausted with the responsibility of “saving the planet” as farmers are with living with disrupting policy and being told they are to blame.

The media conversation has been carefully crafted to steer away from the effects mining, shipping, manufacturing, urbanization and all resource exploration. Instead, we see “solutions” such as carbon credits binding food production land. That soil is our future and it needs to be both enhanced by and protected for farming.

Let’s change the dialogue. There is a time and a season for everything, and now is the time to appreciate and share that man alone does not cause weather events. However, we must collectively strive to understand our earth and respect its natural ecology using its ways of knowing and healing to better our own practices. The answers surround us.