Crop-guzzling equines once posed serious risk to human health in major cities before an unlikely saviour appeared

Next time someone tells you what the future holds, think manure.

Literally.

That’s the advice of writer Stephen Dubner, who used the tale of a century-old manure crisis to illustrate the folly of predicting what lies ahead.

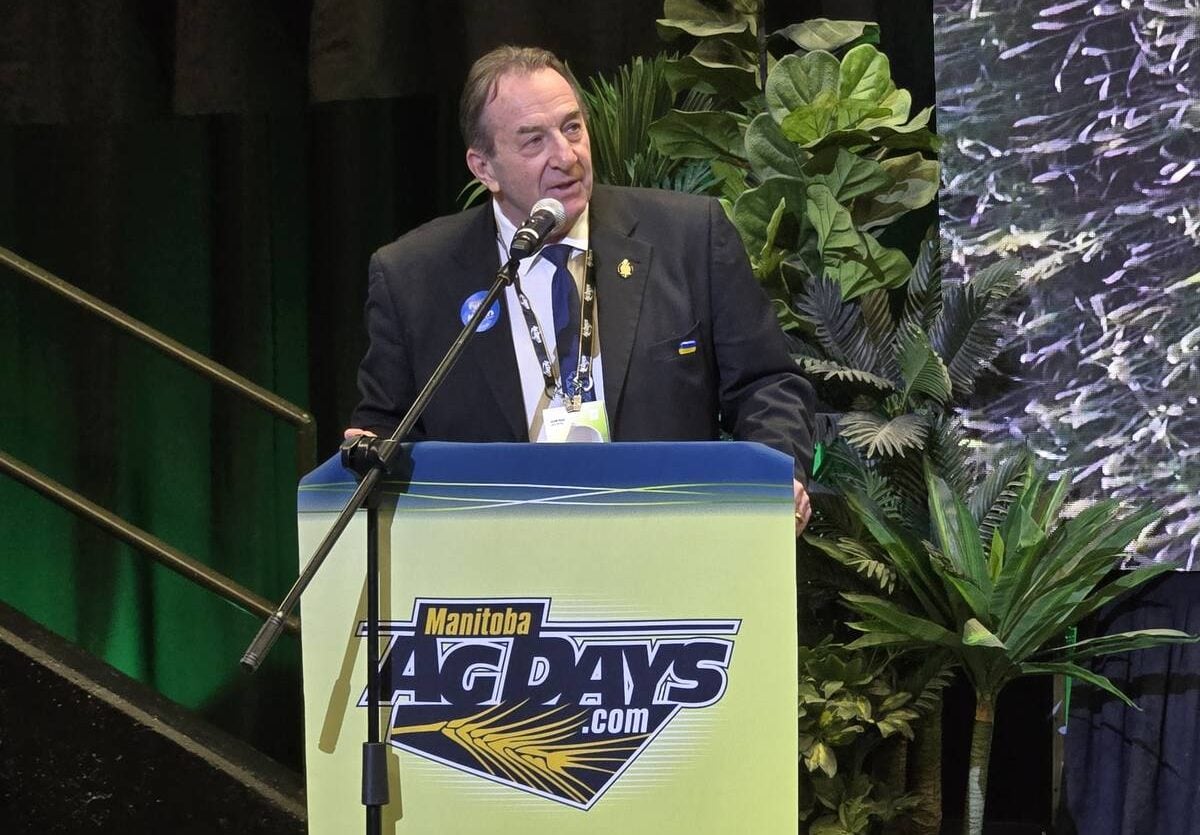

“Human beings are terrible at predicting the future,” the journalist and co-author of Freakonomics told attendees at the Canola Council of Canada conference in the U.S. capital.

At the turn of the last century — as today — there was a food-for-fuel problem. Only then it was grain being used to fuel horses.

Read Also

Manitoba crop insurance expands wildlife coverage, offers pilot programs

New crop insurance coverage is available to Manitoba farmers.

“Crops that would have landed on a family’s dinner table (were) sometimes converted to fuel, driving up prices and causing shortages,” said Dubner, whose bestselling book with economist Steven Levitt was subtitled A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything.

“And then there are the air pollution and toxic emissions endangering the environment as well as individuals’ health.”

At that time, horses were the primary means of transportation in cities, and each produced nearly 25 pounds of manure a day. Initially, this was a good thing as it provided farmers on the city’s outskirts with valuable fertilizer. But as cities grew, a tipping point was reached.

“As more and more horses flooded into the city centres, there was a glut in the market and the market collapsed,” said Dubner.

This was a major issue and a crisis for cities such as New York, which had 200,000 horses in 1900 that collectively produced five million pounds of manure each day.

“The city was really in danger — this was considered a problem of the highest order,” he said.

A host of options was considered, including breeding horses that produced less waste, manure taxes and horse diapers. None were feasible. The issue was so serious that a major conference was called in New York with five days set aside to identify potential solutions. But after just two days, frustrated attendees gave up and went home.

Then unexpectedly, the problem of horse manure disappeared — almost overnight.

“It was solved of course by the invention of the internal combustion engine and the automobile,” he said, noting the New York Times referred to the car as an “environmental saviour.”

There’s a lesson here for today, said Dubner: Solutions to problems come from unexpected sources, and rarely from the industry that is the source of the problem.

The same lesson may apply to current crises of global warming and food production, he said.

“One big mark of our arrogance is our belief in our ability to predict the future,” he said.

“When you look at these problems that seem unsolvable, too complicated, you often just fail to see in history that around the corner — which we can’t see very well — there lies a solution.”