Aproject to preserve natural cover on the steep slopes of the Manitoba Escarpment is being renewed and reconfigured with new funding.

Funds will concentrate on outreach, education, and providing research management planning for landowners willing to preserve tree cover on slopes.

Clearing the slopes of the Pembina Valley and Manitoba Escarpment reduces the land’s ability to sequester carbon and produce oxygen, reduces natural habitats for wildlife, and often causes soil erosion.

People may not understand the value of their forested land, said Cliff Greenfield, manager of Pembina Valley Conservation District. The land may contain firewood, valuable lumber, medicinal herbs, or Indigenous sacred plants.

Read Also

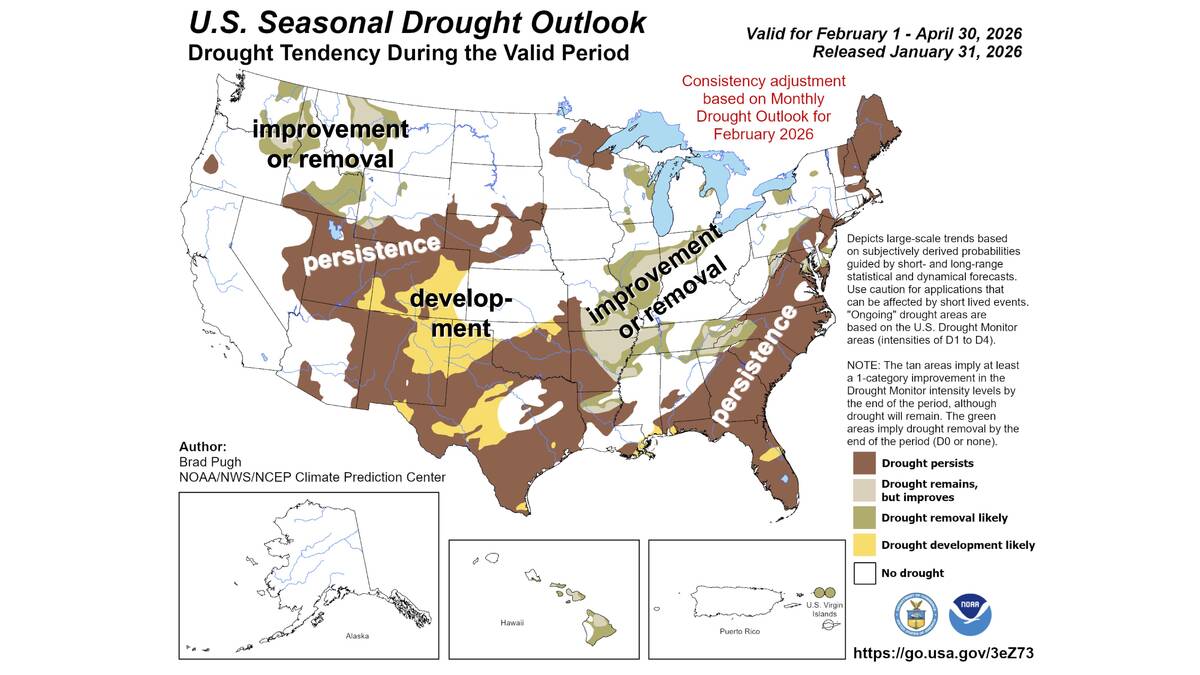

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

Much of the project’s funding will go toward showing landowners how to manage their wooded land, find value in it, and steward it to improve its value.

The two-year project builds on the foundation laid by the Sustainable Slopes Initiative, which ran from 2013 to 2018. The conservation districts of Pembina Valley, La Salle Redboine and Whitemud Watershed will team up with the Manitoba Forestry Association, funded by the Conservation Trust, a Manitoba Climate and Green Plan initiative from the Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation.

“Anywhere you have steep slopes there is a risk of too much water moving too fast down the slope and often bad things can happen,” said Pembina Valley Conservation District (PVCD) vice-chairman Walter McTavish in a news release.

“Having natural vegetation like grasses and trees on and above the slope generally increase infiltration and the water that runs off comes more gently,” McTavish said.

Ten years ago, the districts noticed a trend of clearing slopes for farmland in the escarpment area, said PVCD manager Cliff Greenfield.

This was due to high commodity prices, increased land values, and other economic pressures.

“You gain some farmland, but in some cases the erosion is detrimental to that farmland too,” said Chris Reynolds, manager of Whitemud Conservation District. “There’s all sorts of problems.”

Reynolds said when slopes are deforested, the land loses value as a natural habitat, ability to sequester carbon and generate oxygen, and its ability to stop erosion.

This can also lead to road and bridge washouts, said Reynolds. “Every municipality has their spots.”

Greenfield said the earlier program saw quite a bit of uptake, with several landowners committing to leaving portions of their land in its natural state.

“With farmers there has always been that mindset of stewardship,” said Greenfield.

However, Greenfield said in the scope of things, what land they’ve preserved is ‘kind of a pittance,’ and more work is required.

The previous iteration of the program offered financial incentives to landowners to keep slope cover. In 2015, the Manitoba Co-operator reported that landowners were offered direct payments of tax receipts in return for a conservation agreement — a formal easement on their land title to leave it in its natural state.

Greenfield said they don’t have the funding to enter conservation agreements this time, which may deter some participants.

Landowners interested in participating in the program are invited to contact the Manitoba Forestry Association, or one of the involved conservation districts.