Think climate change is a load of bull? Or do you view it as mankind’s greatest threat?

It’s a heated debate but for plant ecologist Mike Schellenberg, the big question is how ranchers – or, more specifically, the grasses in their pastures – will fare if climate change does occur.

“If the climate warms, the rain pattern changes, and we harvest at this or that date, what is the impact?” said Schellenberg , range and forage plant ecologist at the AAFC station in Swift Current.

Read Also

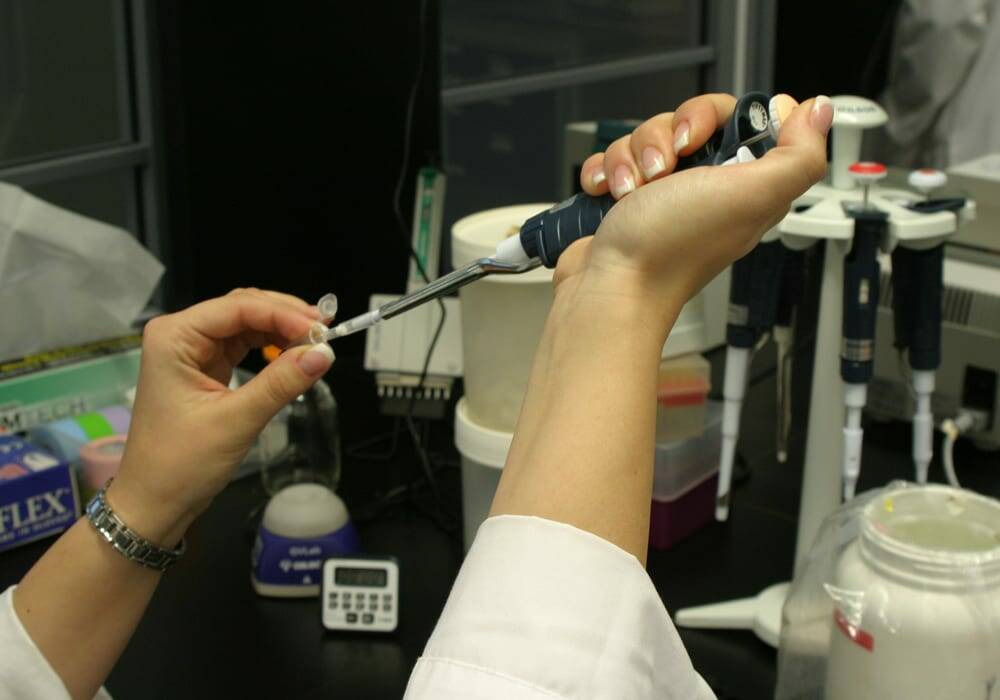

Ship’s turning for gene-edited crops

More and more countries have decided that gene-edited crops will be treated the same as conventional plant breeding.

He’s part of the Sustainable Agriculture Environmental Systems (SAGES) project, in which the effect of higher average temperatures on native grass species is being studied at seven sites across the Prairies and British Columbia.

“This will go into developing best management practices for those types of communities, and (examining) what the differences are going to be across the Prairies.”

The study, launched earlier this year, involves creating a climate- altered world on a small scale.

Open-topped wooden frames covered in clear plastic are used to artificially elevate the temperature by 1 or 2 within a one-metre-square area, and to exclude precipitation at certain times of the year. The grass under the frame is also being clipped periodically to simulate grazing. The idea is to mimic the commonly accepted climate- change scenario in which rainfall patterns are more variable, and possibly shift into a narrower, more intense, window such as early spring.

At the Manitoba and Saskatchewan sites, the potential impact on invasive species such as Kentucky bluegrass and introduced species such as crested wheat grass is also being monitored for clues as to how future trends might play out.

Not surprisingly, given the cool summer with near-record rainfall, more growth was found in the chambers at the Swift Current site than on the unaltered areas nearby.

It’s still too early to discuss results after just one year in the three-year study, but researchers are paying close attention to the potential effect on both warm-and cool-season grasses.

Warm-season grasses are typically C4 plants, like corn, and their cool-season counterparts, like wheat and rice, use a C3 photosynthetic process. It’s theorized that more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere might provide a boost for cool-season grasses, but the Swift Current study has already suggested that climate change might give the C3s an added advantage.

“With spring seasons that are warming up earlier, you get (earlier) activation of growth for your cool-season grasses,” said Schellenberg.

“By the time you get to temperatures and conditions when your warm-season grasses can grow, which tends to be in late June to July, your cool-season grasses have already captured most of the resources available.”

Studies in Colorado have also shown warm-season grasses being overtaken by their cool-season rivals. In another Swift Current study unrelated to the SAGES project, warm-season C4s such as little bluestem and switchgrass seeded in small plots faded quickly, said Schellenberg.

“They did not last,” he said. “They were gone in two years.”

This year’s cool, wet weather may seem to be a rebuttal to climate-change arguments, but there are many explanations for a short-term change in the weather. One is the Icelandic volcano earlier this year, which shot ash and particulates high into the atmosphere effectively “seeding” the clouds and deflecting sunlight back into space.

But it’s the longer term that counts, said Schellenberg, noting temperatures in Swift Current have risen by roughly 1 degree in the past 50 years.

“At Swift Current, over a 50-year period, there has been a significant increase in temperature recorded,” said Schellenberg.

“The main impact seems to be earlier springs, and the nighttime temperature is increasing as well.”

Less snow is falling on the area, he added, but more rain is falling, and most of the increase is coming in June.

While areas of Saskatchewan and B. C. are predicted to become hotter and drier, Manitoba is likely to get wetter under the latest climate change models, he added. [email protected]

———

“If the climate warms, the rain pattern changes, and

we harvest at this or that date, what

is the impact?”

– MI KE SCHELLENBERG, AAFC PLANT ECOLOGIST