Peas, lentils and beans got a big boost to their public profile thanks to the UN’s International Year of Pulses in 2016. Soils got a similar treatment a year earlier. In 2026, it will be all about grazed land.

WHY IT MATTERS: Grassland habitat has been quickly disappearing on the Canadian Prairies and conservation groups note that livestock have a critical role in maintaining what’s left.

Last March, the UN General Assembly officially declared 2026 the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists.

Read Also

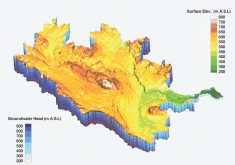

Where’s the water? RISMA knows

National soil moisture sensor network gives real-time data for Manitoba farmers fighting more frequent drought or flood.

While it’s tough to get people excited about an event that’s still three years away, the increased attention is important due to the ongoing threat to this critical habitat, said the co-chair of the North American support group for the event.

“We’re losing native grasslands,” said Barry Irving, who was a long-time manager of the University of Alberta’s research stations. “We have all these wonderful programs and information, but there’s still a ton of native grassland that is converted [to cropland] every year.”

According to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, more than 70 per cent of the country’s prairie grasslands have been lost, and another 148,000 acres are plowed or developed every year.

“The International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists aims to raise awareness and advocate for the value of healthy rangelands and sustainable pastoralism, as well as advocating for the need to further build the capacity of and increase responsible investment in the pastoral livestock sector,” the United Nations said when it announced the event last year.

A lot could be accomplished by raising awareness of rangelands with people who rarely step foot on them — the urban population, according to Irving.

“That’s the group that could have some effect on future arrangements,” he said.

Duncan Morrison, executive director with the Manitoba Forage and Grassland Association, welcomes such a large-scale celebration of rangelands.

“It’s quite significant,” he said. “It’s just well-timed in terms of some of the challenges and successes of grasslands.”

Morrison also pointed to disappearing grassland acres. Economic decisions on the farm have contributed to the vanishing act, he noted.

Gearing up

Irving’s group is one of 11 worldwide that are working on preparations for the international year.

“North America will take more of a focus on rangelands, but other places in the globe will take more of a focus on pastoralists,” he said.

Originally, the focus was going to be on rangeland alone. Then planners realized pastoralists, who collectively care for an estimated one billion animals globally (from sheep, goats and cattle to camels, yaks and reindeer) also required recognition.

When it comes to protecting rangelands, there are short- and long-term forces at play, said Irving.

“A balance needs to be had. When resources become limited, they become more valuable.”

Eventually, the value of rangeland will become high enough — through conservation program payments or long-term leases — to keep it native, he hopes.

There is some movement in that direction.

In addition to the efforts of conservation groups, Ottawa created the On-Farm Climate Action Fund, which could help keep ranchers on the land, Irving said. There is also more messaging focused on the role of rangelands.

However, Irving added, the losses continue. He estimates that parts of his home province of Alberta now have about 20 per cent of their original native rangeland.

Not all of that loss is on private land, he noted, pointing to occasional public land dispersal auctions by government entities.

Irving said it is vital to make more people aware of what’s happening and its impact.

“That awareness goes beyond the sustainability of land; it’s sustainability of culture, lifestyle, communities.”

His group was active among the long list of individuals and organizations working to get the international year declared. There were about 50 people on the committee, which was loosely affiliated with the Society for Range Management, headquartered in Kansas.

“We accomplish[ed] the unknown, which was getting the U.S. and Canada to sign on formally as endorsing the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists,” he said.

“Typically, Canada, United States, European Union and Australia do not sign on to formally support international years.”

Domestic reluctance was based on fear that signing on would equate with help to foot the bill, he said.

Globally, more than 300 groups, including UN agencies and the International Livestock Research Institute, collaborated to get the international year declared.

Proponents first needed approval from the UN’s committee of agriculture. Then the proposal had to work its way up to the General Assembly.

In Irving’s view, it’s not what happens in the higher echelons of government and the UN that is key. It’s the actions in ranching and farming communities.

“It’s a grassroots movement, I think. It moves from the ranch or farm individual on up.”

As far as Morrison is concerned, the three-year lead-up is a perfect window to promote rangelands’ role in sustainable development.

“It is a chance to showcase these lands. It is a chance to showcase that, as well as being working landscapes and being a critical part of farms in Manitoba and on the Prairies, that these particular ecosystems are incredibly valuable and we need to continue to build attention around them,” he said.

— With files from Alexis Stockford