Mario Tenuta, a soil science professor at the University of Manitoba and research chair in 4R nutrient management, wants to see more nitrogen-fixing legumes in Prairie field crops.

After all, one way to avoid nitrous oxide emissions is planting crops that need little or no commercial nitrogen.

“When any form of nitrogen is added to soil, it will emit nitrous oxide,” he said. “Even if we didn’t apply any fertilizer, [the field] would emit some. But when we apply fertilizer, a lot is emitted.”

Read Also

Air, land and sea join forces as Manitoba launches Arctic trade corridor plans

Manitoba wants to take its Arctic trade routes to the big leagues. The Port of Churchill, CentrePort Canada and Winnipeg airport have all raised their hands to help it happen.

Why it matters: Producers are being pushed to be more efficient when applying nitrogen, given a federal target to cut nitrogen fertilizer emissions by 30 per cent over the current decade.

With their ability to fix nitrogen directly from the air, most properly inoculated pulse crops offer a way to sidestep the use of nitrogen fertilizer.

That’s not just a win in terms of nitrous oxide emissions, but could also take a bite out of carbon dioxide emissions. That gas is a product of nitrogen fertilizer manufacture, Tenuta said during Ag Days 2023 in Brandon, pointing to the fertilizer plant that sits on the outskirts of the city.

Navigating a minefield

The future of nitrogen has become a fraught conversation topic, given calls to decrease fertilizer-linked production of greenhouse gas. Critics of the government’s fertilizer emissions reduction goal worry about its impact on farm production and have criticized what they see as a gateway for over-regulation.

In Tenuta’s view, the issue has become over-simplified, political and controversial.

He argues that nitrogen fertilizer use can be reduced without lowering productivity and could help rather than hurt farmers. He pointed to the huge jump in nitrogen prices.

A recent survey of fertilizer prices done by Manitoba Agriculture found that a farmer who bought spring nitrogen last fall paid twice as much as at the same time the previous year.

“Do you really want this kind of volatility, where the price of your input can rise by 300 per cent?” Tenuta asked.

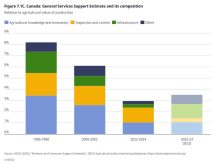

“There is as much N fixed by legumes in Canada as the total use of nitrogen fertilizer in Saskatchewan, which is our largest provincial user of nitrogen by far. This is really important.”

Through his research, Tenuta has observed nitrous oxide emissions compared with nitrogen fertilizer use for a range of crops. When annual crops are grown using nitrogen fertilizer, he said, there’s always a “burst” in emissions.

Tenuta did not see similar burst when the crop in question was a nitrogen-fixing legume that didn’t need that extra shot of N.

“My purpose is not to make your life harder or blame you. It’s to find alternatives. I’m not one of these the-world-is-ending or sky-is-falling people. I am more optimistic than that.”

Past changes

Pulses have already been a major driver of change in annual crop production on the Prairies.

Their introduction to crop rotations helped farmers shift from summerfallow to continuous cropping in the 1970s. The crops were used to control weeds and mine soil carbon in the new system, Tenuta noted.

“There’s lots of research that shows bringing in annual grain legumes contributed to the reduction of summerfallow. Of course, the other big things were glyphosate and direct seeding.”

As pulse acres grew, they had an enormous impact on nitrogen use in the region, Tenuta said.

Talking business

The goal of more nitrogen-fixing crop acres is supported by the pulse sector.

Denis Tremorin, director of sustainability with Pulse Canada, has also tagged his association’s family of crops as a means to limit greenhouse gas in Canadian agriculture.

When it comes to annual crops, fertilizer will drive most greenhouse gas emissions, Ag Days attendees herd. Diesel is also a factor, but it’s a distant second, and greenhouse gases from pesticides or seed production are minor contributors.

Tremorin noted the drive in the corporate world toward ‘net zero’ commitments. Governments are also feeling the pressure of their environmental commitments.

The result is things like rising corporate adoption of regenerative agriculture principles.

“It gets people’s backs up a bit. It’s seen as coming from the food industry,” Tremorin said. “But when these firms come to talk about regenerative agriculture in our systems, we can come back and say ‘yes, we’ve been doing this for a long time.’”

Pulse Canada is working with the food industry to find new and creative ways to incorporate pulse ingredients for the sake of nutritional and environmental targets. Pea flour, for example, is being researched for use in processed foods.

Tenuta noted the Canadian targets to reduce emissions are just that right now — targets, and voluntary ones at that. That’s a different picture than in other jurisdictions like the Netherlands, where hard caps are being set by government.

He is hopeful that, between 4R adoption and other changes to our production system, Canada will never get to that point.

“We need more grain legumes,” he said. “It’s an important part of our emissions reduction picture. We shouldn’t just rely on 4R, but also include grain legumes.”