Britons are flocking to their local butchers after horsemeat was discovered in a wide variety of frozen foods and restaurant items

In one of Britain’s oldest butcher shops, staff in straw hats are rushing to cope with a surge in demand for pricey pies and sausages from customers worried about a scandal over mislabelled horsemeat.

Founded in 1850, Lidgates in London’s smart Notting Hill district retains a Dickensian atmosphere, but very different prices. A whole beef fillet sells for more than $160 and half a dozen sausages are $9.

But business is booming these days.

“Sales on items such as minced beef, pies, sausages went up ranging 10 and 20 per cent directly on Day 1,” said Danny Lidgate, 33, the fifth generation of his family to run the shop.

Read Also

Canadian cattle industry has wins to shout about

Canada’s cattle management has become more efficient, more humane and more knowledgeable, but industry terms may not resonate with the general public.

The trend towards upmarket meat appears to be gathering pace elsewhere in horse-loving Britain, where many people are so sentimental about horses that they find the idea of eating their meat repulsive.

According to the Q Guild, which represents high-end independent butchers, its members say sales of beef burgers and meatballs have risen by 30 per cent since the horsemeat furor started.

Generally, horsemeat is not a danger to health, but the damage to public confidence has already been done.

Rib-eye steak

Scrutinizing a cut of rib-eye steak, Jacqueline O’Leary, a housewife from the upscale Kensington district, said she’s changed her shopping habits.

“I haven’t bought lately (from supermarkets). I’ve just been buying more here so they’ve probably seen me three times a week and I buy sausages and mince from here now, it’s just easier.”

Upstairs in Lidgates’ busy kitchen, a butcher completes a cottage pie, the traditional British dish of minced meat covered in a layer of potato. At $8 a portion, the fresh grass-fed or organic minced beef dish is five times more expensive than the alternative from frozen food giant Findus, at the supermarket.

After finding beef lasagne contained horsemeat, the British unit of Findus began recalling the product from supermarket shelves last week on advice from its French supplier Comigel, raising questions over the complicated nature of the European food chain.

Elsewhere in London, Mark McCartney, another shopper, said he would rather go to his local butcher than buy meat at the supermarket.

“I trust this meat more than I trust anything out of the supermarkets and you can pick and choose and give this man the money,” he said. “It’s cheaper, it’s better quality and it’s better people getting the money.”

Many expect shoppers will return to their old buying habits once the controversy fades, but even a temporary reprieve is welcome for the nation’s butcher shops, whose numbers have fallen from 9,000 at the start of the century to 6,800 in 2011.

At a bustling London street market, butcher Raymond Roe said he had been in the trade for 37 years but at least eight of his local competitors had closed their doors since 1976.

Even though shoppers are angry with supermarkets now, he was pessimistic about the future.

“They’ve lost their trust,” he said. “I get a lot of people saying they’re not going to buy from them. But the thing is, supermarkets are convenient for everyone and most people haven’t got much time. A lot of it is, people don’t cook anymore.”

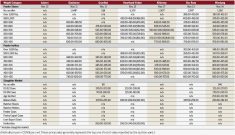

Pointing behind him on the wall to diagrams of animals with lines drawn to indicate cuts of meat, Roe described his role as butcher, teacher and chef for his customers.

“I show them the charts where the cuts come from to try and educate them because years ago, the older people — a lot of them are dead now — they knew the cuts but no one knows anything now,” he said sadly. “They don’t even know how to cook.”