“A lot of poultry houses haven’t kept up.”

– MICHAEL CZARICK, UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

In the last 20 years, average live turkey weights have greatly increased. Today, thanks to improved genetics and management, a 42-day-old tom is 25 per cent heavier than it used to be.

That means birds generate 25 per cent more heat than before. And ventilation systems in many turkey barns haven’t changed to handle that.

They should, says Michael Czarick, a U. S. agricultural engineer specializing in environmental management for poultry barns.

Read Also

Tie vote derails canola tariff compensation resolution at MCGA

Manitoba Canola Growers Association members were split on whether to push Ottawa for compensation for losses due to Chinese tariffs.

Even new barns are often built to outdated standards, he said.

“The fact of the matter is, the birds have changed and become more fragile. It’s a higher demand for having an optimal environment. And a lot of (poultry) houses haven’t kept up with it,” Czarick said after speaking to a recent Manitoba Turkey Producers seminar in Winnipeg.

“I go to so many houses, they’ve built a brand new house and it’s technically a 30-year-old house.”

That’s not to say turkeys die in inadequately ventilated barns. Like most modern poultry, turkeys are high-performance birds which will grow in almost any house, Czarick said.

But to reach their full genetic potential, they need an optimal environment which higher ventilation standards can provide. Birds stressed by heat or cold have poorer feed conversion and lower weight gain, he said.

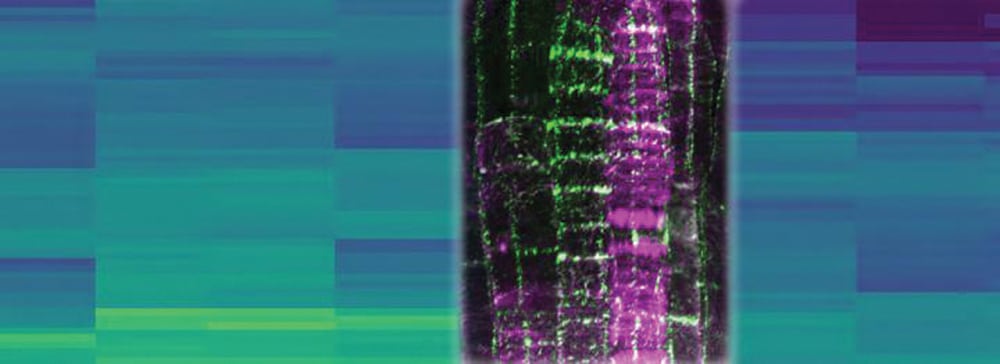

Czarick gave a PowerPoint presentation with infrared photos of turkeys in barns. The pictures showed red and blue blotches, representing heat and cold, frequently in the wrong places because of improper ventilation design.

Hot air would accumulate in the centre of the house while cold air entering from wall inlets got dumped on birds’ heads. Birds near the walls would huddle together while those in the middle were overheated.

A common response is to increase the number of fans in barns to boost exhaust and air circulation.

But doubling the number of air inlets is better, not to say cheaper, than doubling the number of fans, said Czarick, an extension engineer at the University of Georgia at Athens.

Eighty per cent of an effective ventilation system consists of good inlet design – having an adequate number of air inlets properly spaced, he said.

But fans are still necessary to provide air flow over birds in hot weather. Moving air removes heat from birds and reduces their need to cool off by panting, which increases evaporation from the body.

“We don’t want the bird to cool itself. We want to cool that bird,” Czarick told producers.

He recommended designing ventilation systems in turkey barns for cold, moderate and hot weather conditions. Cold weather systems maximize heat by reducing air flow and avoiding air leakage from the outside. Moderate weather systems require some temperature control, while hot weather systems emphasize air movement to prevent heat buildup.

Although Czarick is from Georgia, where weather can be very hot and humid, his principles for ventilation design also apply in Manitoba, said Bill Uruski, Manitoba Turkey Producers chairman.

“The comfort of the bird is of utmost importance in terms of raising a good product for the consumer,” Uruski said.

Some of Manitoba’s 59 registered turkey producers (51 commercial and eight breeders) either range turkeys out of doors or have free-run operations. But most larger growers today raise turkeys indoors. [email protected]