The number of Manitoba farms peaked in 1941 and ever since they’ve been getting bigger in size and fewer in number — a trend that shows no signs of stopping.

Some call that progress, others preposterous. Darrin Qualman is among the latter.

The National Farmers Union’s (NFU) director of Climate Crisis Policy and Action says without government intervention half of Canada’s farmers will leave the land over the next generation or two.

That means not just fewer farmers, but even fewer young farmers, a less climate change-resilient farm sector, a decline in the rural economy and farmers’ political clout and further concentration of wealth, according to a paper Qualman and four others wrote entitled ‘Concentration Matters, Farmland Inequality on the Prairies.’ It was released recently by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Read Also

AAFC organic research program cut

Canada’s organic sector says the loss of a federal organic research program at Swift Current, Sask., will set the industry back.

To make farmland ownership more equitable the paper suggests “imposing limits on the area any one entity can own as is done through the Lands Protection Act in Prince Edward Island.”

It says governments should modify farm-support programs and tax laws to counter market forces pushing farms to get bigger to serve export markets.

It also proposes developing land access programs for young and new farmers, including Indigenous peoples and “redirecting research away from industrial models toward organic production, small scale, diversified, agroecological, local production, and similar approaches and generally restructuring Canadian agricultural policy toward a focus on maintaining the maximum number of farmers…”

Without government action Manitoba is headed to as few as 200, 50,000-acre farms, according to Qualman.

“That’s not an outrageous idea that if something isn’t done you might get down to 200 farmers farming all the cropland in Manitoba in a generation or two,” he said. “Nobody wants to go there.”

Perhaps, but University of Manitoba agricultural economist Derek Brewin doubts government regulations can stop farms from expanding as market forces push them to be more productive.

Moreover, such regulations are likely to make farmers less competitive.

“If you want to make supply chains more expensive you could force a bunch of size restrictions,” he said in an interview Nov. 25. “That’s what it would do to the beef sector, that’s what it would do to the crop sector too. You would actually make things more expensive if you took away all the incentives for capturing the economies of scale.”

Why it matters: Large farms are very efficient farms, but should public policy aim to level the playing field? And will that make the sector less competitive?

Farm robots and artificial intelligence have the potential to make farms bigger yet, he added.

Meanwhile, the paper co-written with Annette Aurélie Desmarais of the University of Manitoba, André Magnan of the University of Saskatchewan, and Mengistu Wendimu, an economic analyst at Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development and an adjunct professor at the University of Manitoba, says bigger, but fewer farms is not in the interest of farmers or the Canadian public.

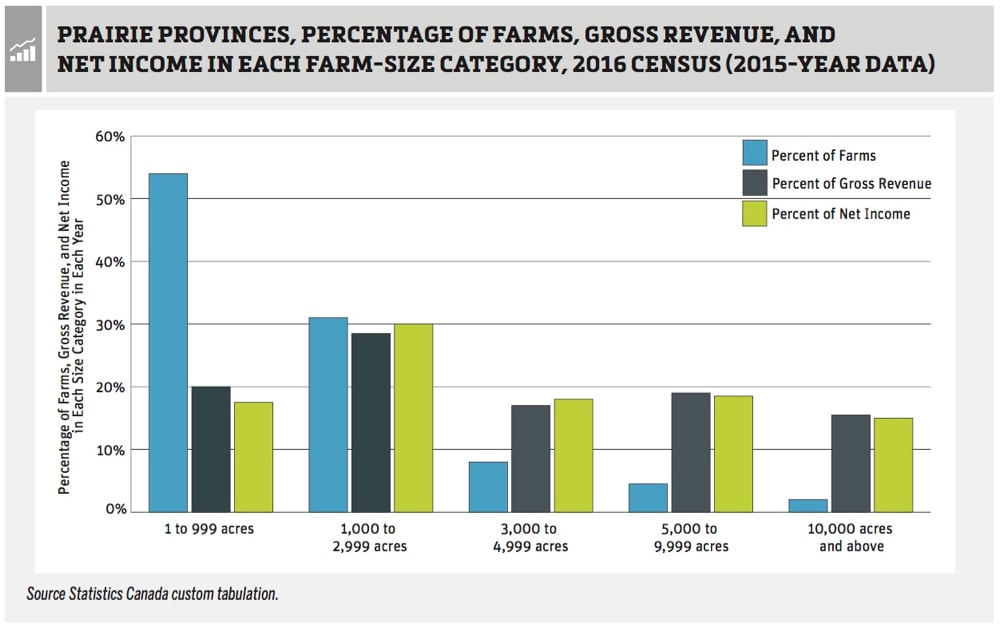

“(O)ne cannot help but conclude that unless government policies or economic shocks alter these trends, 20 years from now, the area of land operated by small farms will be negligible, and farms larger than 5,000 acres may operate 50 to 60 per cent of Prairie farmland up from about 37 per cent today,” the paper says.

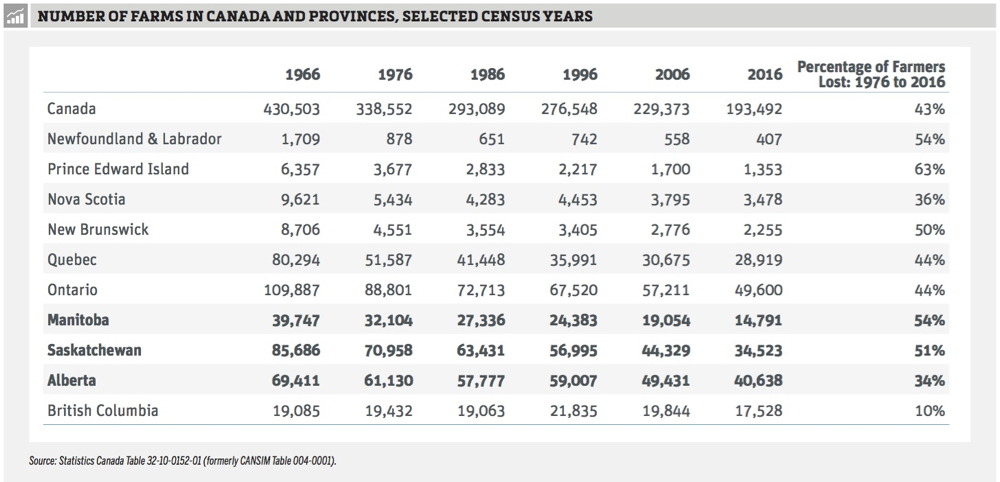

Farmland concentration isn’t new. In 1966 there were 39,747 farmers in Manitoba, the report says, citing figures from Statistics Canada. By 2016 there were 14,791 — a drop of 54 per cent.

Manitoba farms peaked at 58,024 in 1941, averaging 291 acres, wrote Morris Deveson in a history about Manitoba agriculture (read ‘Worries about fewer, bigger farms not new‘ at bottom).

By 2016 the number of Manitoba farms had fallen 75 per cent with a 310 per cent jump in average size.

“A small and declining number of farms are operating the lion’s share of Prairie farmland,” the paper says. “Not surprisingly, a small and declining number of farmers are capturing the lion’s share of farm revenue and net income.”

While the number of total farms has been declining, the number of operations run by young farmers has been declining twice as fast, Qualman said.

Fewer small farms means fewer young farmers because young farmers typically start small, he said.

The Keystone Agricultural Producers (KAP) has also raised concerns about young farmers getting into the business, especially when it comes to acquiring land.

“It’s extremely frustrating for me and many young farmers in this area (near Elie, Man.),” Rauri Qually said during KAP’s advisory council meeting July 30. “We want to farm, we want to buy new equipment, we want to help our communities and economy grow, but if we aren’t even allowed to take a bat up to the plate how can we have a chance at any of this?”

KAP has been investigating the role conservation groups and foreign buyers have on Manitoba farmland prices.

Qually has also proposed KAP explore tax incentives to encourage retiring farmers to sell or rent to young farmers.

According to the paper, allocation of farmland on the Prairies is inequitable and going to get worse.

“Most farmland is bought and sold in open markets, allocated according to ability to pay,” the paper says. “Who has the greatest ability to pay… ? Often it is those who already have the most acres paid for, often those who operate the largest farms.”

But some agricultural economists say that’s exactly how it’s supposed to work in a market-driven economy. During an interview before his death in 2003 University of Manitoba agricultural economist Daryl Kraft said farmers have been forced by markets to increase productivity because “real” (adjusted for inflation) prices for crops have been declining since 1918.

The push to boost productivity also drives farm size as farmers replace expensive farm labour with equipment and technology, Brewin said.

“One of the big reasons we are seeing (farmland) concentration is economies of scale in that equipment line, (spreading the cost over more acres),” he said.

Qualman says it’s because farm input suppliers and commodity buyers have the market power to cut into farmers’ margins.

“We can all remember people supporting a family really well on 1,000 acres and now because the margins per acre have fallen so far it might take 5,000 or 10,000 acres to do that,” he said.

“And it just doesn’t stop.”

Brewin doesn’t believe government intervention will end farm consolidations.

“In the supply management sector where all the margins are protected (for farmers)… they get bigger too,” he said. “You can’t say there has been an increasing number of any of those (supply-managed) farms and that’s a pretty drastic market intervention. I don’t disagree that there could be too much concentration in some of those sectors (inputs), but there are reasons for a bunch of that as well. There are a lot of economies of scale in inputs manufacturing.”

Land banks were tried in Saskatchewan and Manitoba and they didn’t stop farms from getting bigger, Brewin added.

The local food movement is working without government intervention, he said.

“One per cent of Manitoba’s farmland could feed Manitoba,” Brewin said. “I don’t think we should structure our ag policy to solve that problem.

“We have more arable land per person in Canada than anywhere in the world except Australia and Kazakhstan. We have excess productive capacity and we will export. I don’t think whatever we did we could not have exports. If you try to supply manage grain it would be just cutting off huge amounts of economic productivity…”

Worries about fewer, bigger farms not new

The disquiet over the continuous trend to fewer, bigger farms in Manitoba has existed since farm numbers peaked here in 1941.

This reporter wrote about it in a 1971 high school speech entitled ‘The Death of Mr. Small Farmer.’

“And it will come to pass, as it did to me in a great vision, those, black evil letters O-B-I-T-U-A-R-Y. On Nov. 5, 1987, in the hospital for old institutions Mr. Small Farmer passed on,” went the opening refrain.

The piece, allegorical and rhetorical, long on emotion and short on facts, reflected the times. Prairie farmers’ bins were bursting with three years of wheat. The federal government, through Operation LIFT (Lower Inventories for Tomorrow), was paying $6 an acre to summerfallow wheat land.

The years leading up to 1971 had been tough. In 1967 wheat and dairy farmers, angry about surplus production and low prices, threatened a strike leading to a farmer protest on Parliament Hill that same year.

That prompted the federal government to create the Federal Task Force on Agriculture. The Canadian Encyclopedia says it delivered its report entitled Canadian Agriculture in the Seventies in 1969.

“It (task force) found widespread dissatisfaction with low farm incomes, uncertain markets and prices, overproduction, small nonviable farms and diminishing export markets. It recommended that the government should reduce its direct involvement in agriculture and phase out subsidies and price supports, that the farm population should be reduced, and that younger low-income farmers should leave farming while older nonviable farmers should be assisted to achieve a better standard of living. Convinced that the surpluses of wheat and dairy products would continue in the 1970s, the commissioners recommended that farmers shift to producing other commodities.”

Coincidently the National Farmers Union (NFU) was founded in 1969. It strongly condemned the task force report. Some veteran NFU members still sometimes attack the report more than 50 years later.

But according to the Canadian Encyclopedia the government didn’t follow through on the controversial report: “The major agriculture and food policies of the 1970s that grew out of this report were ironically characterized by greater interdependence between government and agriculture rather than by the looser ties the task force recommended.”

For example, federal government introduced supply management for dairy, eggs, and poultry production — a policy the NFU strongly advocated and defends to this day.