Canada’s shipping container crunch is hurting not just farmers but the entire economy. So says a cross-commodity coalition urging the Canadian government to take the lead in fixing it.

“It’s not a normal functioning market,” Greg Northey, Pulse Canada’s vice-president of corporate affairs, said in an interview Dec. 15.

Pulse Canada and several farm groups are part of the coalition with the Freight Management Association of Canada and Responsible Distribution Canada.

“The whole ecosystem in (the Port of) Vancouver is just broken, it’s just completely broken as far as the proper movement of these things,” Northey added.

While Canadian farmers, especially pulse growers, count on containers to export products to more than 100 countries, Canadian consumers rely on them for imports of everything from fresh produce to big-screen TVs.

But to maximize profits shipping lines are sending empty containers back to Asia as fast as they empty, making them unavailable to back haul Canadian crops — a long-standing traditional.

Meanwhile, the cost of shipping containers from Asia to Canada has risen eightfold from around $3,000 to $25,000, making imports more expensive, contributing to inflation and hurting the economy, Northey said.

The cost of shipping a filled container back to Asia, if one can be found, has more than tripled to $5,000 from $1,500, he said.

The disruption was triggered by COVID-19. The pandemic closed many Asian manufacturers for a while reducing the supply of consumer goods.

Later North American demand for those goods took off, but in the meantime container shipments were out of sync.

The result? Chaos.

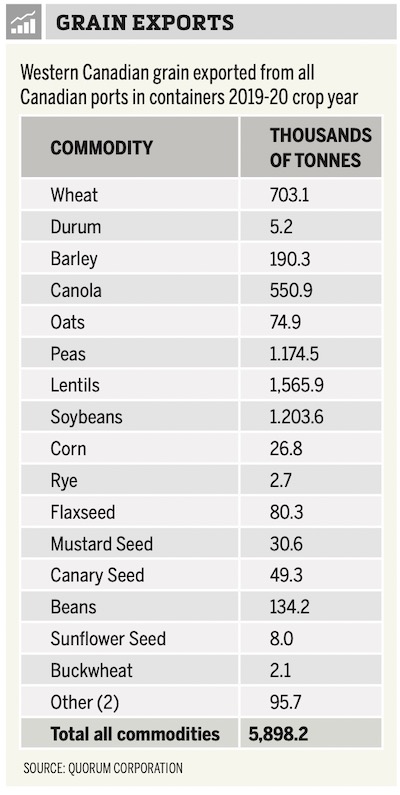

Why it matters: A substantial volume of Canadian farm products are exported in containers, totalling almost six million tonnes in 2019-20.

In 2019-20 Canada exported 1.3 million tonnes of lentils in containers (see table). About 50 to 80 per cent of lentils exported from Vancouver normally leave in containers, Northey said.

“There are shippers in Canada who 100 per cent relied on that (container) supply chain and it’s not there for them anymore,” he said.

“It’s bringing huge disruptions to the industry. It’s not that nothing wants to move, but quite literally (almost) nothing can move in containers.”

Indeed, transloading company Ray-Mont Logistics, which shipped 4,500 containers of Canadian farm products a month in 2019 from Vancouver, now does about 1,000 ag containers, Stephen Paul, the company’s vice-president and chief operations officer told the University of Manitoba’s online Fields on Wheels conference Dec. 14.

That’s a 78 per cent drop.

Ray-Mont cut its Vancouver staff by about the same percentage.

“Where we used to be 24 hours a day and we had upwards of 90 to 100 staff, we’re now doing five days a week operations with 20 staff,” he said.

“Vancouver has become essentially a storage yard for containers… ”

For Canada, a trading nation, that’s not good, Northey said.

Instead of loading and shipping containers, Ray-Mont’s Vancouver operation has pivoted to storing them before they get shipped back to Asia.

“This is now the primary source of our business at this stage in time,” Paul said. “Our focus is still on export transloading for agricultural commodities. That is the root of our company and when the volumes come back we’ll be prepared to offer, but it really has changed the dynamic there.”

Ray-Mont’s facility at the Port of Montreal is shipping a few more ag containers — around 2,000 a month compared to 1,000 to 1,500 a month in 2019, Paul said.

Normally, farm products are exported through Vancouver because of cheaper freight rates, he said.

Shipping lines’ drive to return empty containers to Asia faster is having a knock-on effect and may in fact slow their return, Paul said. Instead of shipping full containers inland to Toronto and places between, they are being unloaded in Vancouver.

“It’s created a shortage for container storage, it’s created a shortage of warehousing space and it has created a shortage for transportation (to move cargo into warehouses),” Paul said. “All three of those sectors, and the pricing associated with it, have been driven up dramatically.”

Meanwhile, even if Ray-Mont can get a container, and if it’s not too expensive, shipping lines no longer ship to India, South America or the Middle East.

“How can I ship through Vancouver effectively if I can’t reach the markets my customers want to ship to?” Paul asked.

In June Ray-Mount had 2,200 loaded containers with a carrier which discontinued service to the port the containers were destined for. The line then said it would deliver a certain number over time. It took six months.

“What I fear for Vancouver is that a perfect storm is brewing,” Paul said.

If there’s a big Canadian crop in 2022 and the container market doesn’t improve “we’re going to be stuck with an unprecedented scenario,” he said. “We’re going to have tremendous demand to move cargo. The volume will be there… but the supply chain, how is it going to react?”

Paul said part of the problem is decisions are being made in isolation, by people in Asia and Europe who don’t understand the Canadian market.

“Trying to increase the turn times of their (container) assets you could probably argue they (shipping lines) reduced it, because instead of containers getting loaded on rail and going to established infrastructure in the East, they are now getting bottlenecked sitting on the Port at Vancouver waiting for warehousing, waiting in container yards like ours… at a different cost,” Paul said. “You have to look at the whole supply chain and look at what ripple effects a decision will have.”

The container crunch coalition went public with its call for government action in October. Since then Ottawa has acknowledged there are supply chain issues and announced some funding to assist with container storage in Vancouver. But the coalition says the federal government needs to do more in the short and long term, Northey said.

First Ottawa should use Section 49 of the Canada Transportation Act to trigger an investigation into the issue by the Canadian Transportation Agency.

“That can happen now and if anything it can draw attention to the issue,” he said. “People will start to think about it a bit more and make different decisions in the short term. It would basically bring us in line with the U.S. and other jurisdictions to look at the problem… ” he said.

The U.S. has taken action with the House of Representatives, recently passing the Shipping Reform Act.

The coalition also wants the government to strike a task force to meet and find ways to fix the container problem.

Normally in a functioning market, shortages and high prices are controlled by competition, but what’s occurring now is “a market failure,” Northey said.

Historically shipping lines have been exempt from competition regulations and are now taking advantage of it, he said. Three shipping alliances control more than 80 per cent of the global market, Northey added.

“Shipping lines collectively made more money in the first three quarters of 2021 than they have made in the last 10 years,” he said.

“It’s completely absurd how much money the shipping lines have made.

“They have taken money out of the pockets of many, many countries as a result.”

More information on the coalition is available online.