Yes, 2012 was a bad year for aster yellows in canola, but we have to keep this disease in perspective. Sclerotinia and blackleg are potential threats each year, and remain the top two most important canola diseases.

Aster yellows has had only four bad years on the Prairies to date: 1957, 2000, 2007 and 2012. That said, three of those years are fairly recent, and after the heavy infection rates in 2012, aster yellows is a hot topic among growers and agronomists.

Here are 10 questions the Canola Council of Canada agronomy team posed to Chrystel Olivier, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, and her answers.

Read Also

Manitoba sclerotinia picture mixed for 2025

Variations in weather and crop development in this year’s Manitoba canola fields make blanket sclerotinia outlooks hard to pin down

Question 1: Are there differences between varieties when it comes to aster yellows (AY) severity? Does this represent some genetic resistance?

So far, no canola varieties are known to be resistant to AY, but based on field observations during the past 15-20 years, B. rapa seemed to be more susceptible to AY compared to B. napus, B. juncea or S. alba. However, no laboratory work was done to investigate the cause of the difference in susceptibility.

This summer of 2012, differences in the percentage of plants expressing symptoms were observed between cultivars for B. napus and S. alba, in the AAFC experimental nursery (small plots). No laboratory work was conducted to explain the difference between the percentages of symptomatic plants.

Note: Trials in small field plots at the AAFC farm showed differences in the percentage of AY-infected plants between lines of Camelina sativa. Insect sampling revealed that there were fewer leafhoppers in the lines showing few (or no) AY symptoms.

These results suggest that feeding preference from the leafhopper might influence the percentage of AY infection among the plants. These results, although promising, need to be taken carefully as feeding preferences might not have a major impact on AY infection in large field acreage.

Question 2: Can infected seed carry aster yellows on to the next generation?

It has always been admitted that phytoplasmas could not spread via seeds. However, phytoplasma DNA was found in seeds and/or embryos of several plant species in Canada (B. rapa, B. napus), Europe (B. rapa, tomato and corn), Oman (alfalfa), Africa (Coconut palm), Peru (corn) and Asia (mulberry).

In most cases, phytoplasma DNA was found in the embryos and the early-seedling stage. The exception is alfalfa where one seedling out of the 84 tested grew with phytoplasma symptoms. Recently, several articles in Europe started to mention that “a low percentage of seed transmission should be considered for phytoplasma.”

Question 3: Can perennial weeds provide an overwintering bridge for aster yellows? If yes, which weed species are more likely to have the disease? And what is the likelihood that the disease will transfer from weed to crop next year?

Perennial weeds and plants — including dandelion, shepherd’s purse, most pasture grasses and common shrubs and trees such as raspberry, willow and chokecherry are potentially a strong disease reservoir for phytoplasma and the likelihood of AY being transmitted from the reservoir to the crop is high.

However, no study has been conducted to know the extent of the infection among the perennial weeds and plants. Studies in carrot crops in the U.S. showed that weed management is important to reduce leafhopper population.

Note: Based on PCR tests done on leafhoppers sampled in Saskatchewan, a steady decrease of AY infection was observed from 2000 (outbreak year) until 2003 (eight per cent in 2001, five per cent in 2002 and three per cent in 2003). Knowing that in 2001-03, the amount of migratory leafhopper that were infected was very low, the percentage of infected leafhopper observed in 2001-03 could be explained by the presence of a high number of AY-infected weeds and grasses following the outbreak year.

Question 4: Some growers claim that insecticide applied for other insects also seems to have reduced aster yellows. Is this possible?

It is possible that some growers might have caught the bulk of the AY-infected leafhopper a few hours or day after the migratory leafhoppers arrived in their crops. However, I have heard both sides of the story: some growers sprayed at the same time as the neighbours with no positive results, while the neighbour seems to have a less infected crop.

In order to have successful spraying, insecticides should be applied very quickly after the migratory leafhoppers arrive, as leafhopper can transmit AY in less than eight hours. Leafhoppers could arrive very early in the season.

Question 5: Why were leafhopper phytoplasma carrier rates so high this year? What is happening down south in their overwintering areas to cause this? How does insect ecology correspond to disease epidemiology?

Based on observations/surveys made during the last outbreaks, several hypotheses have been advanced, but never really proven.

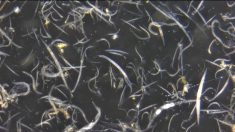

Mild winters caused by climate change are increasing the survival of overwintered leafhoppers, plants and phytoplasma. This year, in the Prairies, all leafhopper species were very abundant. The number of the main AY vector M. quadrilineatus was overwhelming, with thousands found in crops.

Other potential AY vectors were also very abundant. As an example, Athysanus argentarius, an AY vector feeding in the pasture surroundings canola crops, was found on average at a rate of three to four per sweep during the past 10 years. This year, the average was above 200.

Drought also seems to increase the percentage of phytoplasma infection in hosts.

Question 6: The disease survey counts only plants with bladder pods as having aster yellows. Is it true that for every one plant that tests positive for bladder pods, 2.5 are positive by PCR?

PCR tests show that actual levels of aster yellows infection are much higher than what a visual assessment of bladder pods would suggest.

This is true as AY-infected plants do not always show symptoms.

Question 7. Is this statement correct? Thirty to 60 per cent of seeds are usually lost in aster yellows-infected plants, but this year seed loss was significantly higher.

Aster yellows can cause misshapen and malformed seeds, which often shrivel up and blow out of the combine. These can occur in pods that otherwise look normal.

This statement was based on harvesting AY-infected plants in 2001-05 (with infection confirmed with PCR test) and separating normal-looking seeds from small, shrivelled, misshapen seeds.

Small, shrivelled seeds constitute 30-60 per cent of the seeds in AY-infected plants (note that the “empty spots” in the pods were not counted). Due to their light weight, those seeds are usually lost during harvest or spiral cleaning. This statement was still true in 2007, but I don’t think it is true for 2012. In the previous year, 98 per cent of the AY-infected plants had normal-looking seeds and less than one per cent of the AY-infected canola had no seed production. In 2012, based on observations made at the AAFC farm and in several fields, roughly 10 per cent of the canola plants had no seeds and 20-25 per cent of the symptomatic plants contained mostly shrivelled seeds. The rest of the AY-infected plants had a mixture of normal-looking seeds and shrivelled seeds.

Question 8: Are the offspring of leafhopper carriers also carriers? Can phytoplasma transfer generation to generation in the insect?

The main AY vector, Macrosteles quadrilineatus, does not transmit AY via the eggs, therefore offspring do not carry phytoplasma. According to the literature, the other common leafhopper species that transmit AY in the Prairies have never been reported as being able to transmit via eggs. However, Scaphoideus titanus, a leafhopper present in the Prairies in very low number can transmit AY via eggs. Two other leafhopper species can transmit phytoplasma via eggs, but they are exotic leafhopper species transmitting exotic phytoplasma strains.

Question 9: What do you think are the key reasons for the higher outbreak in 2012?

Several reasons might explain the 2012 outbreak.

- Milder winters during the previous years that allow local leafhopper population to survive winter and to build up, hence the high abundance of local leafhopper species observed this year and better overwintering of AY-infected plants.

- The drought and mild winter that occurred in the U.S. this year might have increased the abundance of the leafhopper and their level of infection.

- South winds seem to have arrived in the Prairies earlier in 2012. Below are the arrival dates of the first south wind each year, based on meteorological data. In conclusion, this 2012 outbreak might be due to high inoculum coming early this year.

2001 April 29

2002 May 22

2003 June 20

2004 May 9

2005 May 7

2006 April 1

2007 April 1

2008 April 10

2009 April 11

2010 April 13

2011 April 10

2012 April 1

Question 10: What are the key management techniques growers can follow to reduce severity of the next outbreak?

This is difficult to answer, as we don’t know all the parameters and players involved in the AY epidemiology. An easy way to reduce the incidence would be to reduce the level of weeds in the fields, as it gives leafhoppers food choice.

So far, there is no economic threshold for canola, and no resistant cultivars. If spraying is the grower’s choice, it will need to be very timely (i.e., just after the leafhopper arrival), otherwise, it is not effective.