Technology has advanced with regards to monitoring the health of our cattle, both at calving time and on pasture.

I’ve heard a few presentations, witnessed demonstrations, and have seen use of advanced cameras in the last year at two operations I deal with during calving season. Here are my impressions of them as well.

Video monitoring cameras have been used for years and started with cattle being mere grey blobs. Today’s images are very clear, and the technology now includes high-resolution cameras with telephoto lenses that can pivot 360 degrees and go to infrared technology at night. Even one camera strategically placed in the calving area can cover a big area.

Read Also

Pig transport stress costs pork sector

Popular livestock trailer designs also increase pig stress during transportation, hitting at meat quality, animal welfare and farm profit, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researcher says

The question is how do they help us?

I run a calving rotation for the faculty of veterinary medicine at the University of Calgary, and the learning and teaching experience can be huge with cameras. Showing new employees, students, or urban visitors, a calving cow has many teachable moments. One can focus in on what is protruding from the vulva and determine a malpresentation that needs to be brought in and corrected. Calving behaviour can be taught because it allows one to let more cows calve in the winter naturally outdoors and newborn calves can be brought in right away to minimize the problem of frozen ears. I find that many cows, if disturbed during calving and brought into a barn, cease calving for a while.

Some cameras can even be accessed through your phone, so you can effortlessly check on a cow in labour every 10 minutes if you so desire. Intervention can occur if things are not progressing normally.

This past spring, producers and students were able to avert cows stealing calves or do a few hand pulls right in the pen. An all-too-common complaint is producers losing calves from the water bag being stuck over the nose and a calf suffocating. You can watch on the camera to ensure the water bag has broken or the cow has licked it off. If not, a quick run to the calving area often will save it. When one calf was not reached in time (calved middle of night with the water bag not broken), we rewound the program and found that it had survived about 20 minutes since birth before succumbing — which surprised me. It had been born very quickly (was a twin) so the bag did not break.

Other uses for cameras at calving include being able to see if newborns are sucking, and any change in behaviour and nesting of cows that indicate impending calving. Cows off feed, excessively enlarged, or not chewing their cud can easily be detected. At other times, cameras could be set up in a breeding pen to detect heats for an AI or synchronization programs, or set up around watering bowls or mineral feeders to determine abnormal behaviours, sickness, or lameness.

For all uses, I recommend writing down the ID/description of the animal.

For feedlots, cameras in processing areas can be used for teaching proper techniques and monitoring humane handling. I’ve seen them used to monitor unloading techniques and whether cattle are arriving lame.

Auction markets use them to verify numbers of head whether unloading, through the ring, or loading up. Cameras in the arrival feedlot pen can ensure all cattle are finding feed and water. There are multiple uses for video cameras to improve our management, save more animals, and save labour.

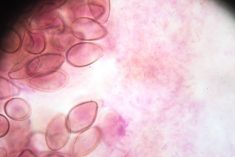

Drones are quite new to the agricultural sector, but Dr. John Church, a professor at Thompson River University in Kamloops, B.C., has done extensive experimentation with drones and sees their huge potential in animal production. Most have cameras that produce crystal clear images. You can monitor the whole herd or drop down and carefully monitor one separated from the herd to look at clinical signs and get identification. They can zip from one side of the herd to another, so it is easy to follow an individual. The telephoto lenses can be phenomenal. Ear tags or other identification can easily be read from 90 feet away, so the cattle are not disturbed. Monitoring bunks and cattle inventory are two additional uses in the feedlot for drones.

Again, the drones can save tremendous time when checking pastures, watering bowls, or mineral feeders. They have been used to locate lost cattle in rugged terrain. Dr. Church has even attached thermography cameras to check body temperatures of cattle with success in controlled settings. They could be used to do checks on calving cows (but since they would be flying low, you would need to accustom the cattle to them first).

On pasture checks, lame animals or bulls with breeding injuries can be identified and location noted for treatment or removal from the pasture. You can also monitor pasture conditions, watering sites, and mineral feeders as well as weeds (noxious and poisonous) and whether gates are closed.

There are many uses for drones or stationary cameras in food animal production. We have probably just scratched the surface as to what monitoring devices, RFID readers, and related technology can do. (However, they are limited by the weight they can carry and most have about a 20-minute flying time.)

Remember, having a recorded image means they are sent on for further evaluation by experts such as your veterinarian, horticulturist, or nutritionist. For example, I look at many recorded videos on sick, injured, or lame bulls for insurance exams. That video can essentially form a medical record and can be compared to a later one to check on improvement.

They say a picture says a thousand words but I would guess a video says 10,000 words. So utilize this in helping with a diagnosis if possible.

This technology is affordable and the payback does not take long. If it helps save a calf at calving, identifies a lame bull more quickly, or finds some lost livestock, the payback is quick.

At a recent bison producers’ meeting in Manitoba, one producer showed how a drone helped him detect a relatively young bison calf was stuck in a badger hole with predatory coyotes close by. Also, if conditioned over time, you can fly very close for visual observation. A bison bull’s tail was actually blowing in the air current from the drone props. (We don’t want to use them for hazing of cattle or other species under observation — we want the drone to be the friend of livestock.)

Consider one for your operation and see what other uses your farm can come up with. Happy grazing this summer.