Many beef producers might remember a time, say 25 years ago, that a 900-pound steer would be considered finished.

Today, there’s a good chance that same steer would be 50 pounds away from starting the finishing process.

Craig Lehr remembers. And on the 25th anniversary of the largest not-for-profit, industry-led funding agency in Canadian beef and forage, he credits research specifically made possible by the Beef Cattle Research Council.

“Because change happens gradually, we as producers sometimes forget the role that research has played in the significant advances of our industry,” said Lehr in his role as BCRC chair in the organization’s 2022-23 year in review report.

Read Also

Winter grazing strategies offer cost relief for Manitoba cattle producer

How cover crops, straw and silage pile grazing fit in a western Manitoba rancher’s winter feeding plan — and how to make sure they meet cattle’s nutritional needs.

Why it matters: The Beef Cattle Research Council has been a key source of production knowledge and data that has helped develop the sector.

The BCRC has evolved with the needs of beef producers who help fund it.

It started as a marketing-focused organization that engaged in one or two research projects per year. Today, the council anchors a research hub with 100 projects at any given time, said BCRC executive director Andrea Brocklebank.

“Governments were moving away from research to some extent and, without industry support, research wasn’t getting funded. That was the real initiation of BCRC,” she said.

Since that time, it has helped supercharge beef and forage research and leveraged Canadian beef cattle check-off dollars into big research funding, said Brocklebank. The BCRC receives 67 cents of every $2.50 collected from producers by the provincial beef associations.

Today, for every dollar it receives through the check-off, BCRC commands $2 to $3 in direct funding from other institutions.

Checking up on check-off dollars

Value for producers’ money is never far from Brocklebank’s mind.

“I’m very cognizant about producers’ hard-earned money. We always want to encourage producers to sign up for our newsletters so they can see what we’re doing,” she said.

“Obviously, it might have direct applicability to their operations, but it’s also just a matter of understanding the extraordinarily important value of this producer investment.”

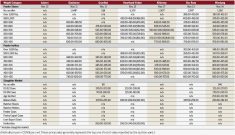

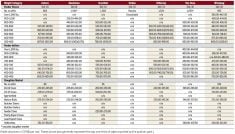

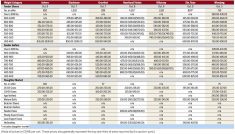

The council has funded nearly $33 million in research and technology transfer over the past five years. Nearly a third, or about $10 million, was in the 2022-23 year alone. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada pitched in nearly $2 million, the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off added $4 million, and another $4.7 million came from other industry and government funding.

BCRC had a couple of wins that stuck out this year, said Brocklebank. A big one was on the animal health and welfare side of its mandate.

A priority research project conducted by Trevor Alexander and his team from AAFC Lethbridge focused on the possible link between calves and bovine respiratory disease when at rest stops during long-haul travel.

The researchers found that calves given an eight-hour rest had higher numbers of BRD-causing bacteria in their respiratory tracts than calves not rested during transport.

“We want to ensure that we maintain healthy animals and, if stress and commingling actually increases risk, that’s a question industry is really focused on right now,” said Brocklebank.

Another study examined the impacts of removing implants and feed additives from feedlot cattle diets.

Kim Ominski of the University of Manitoba and Tim McAllister of AAFC Lethbridge compared results from three feedlot diets: a conventional diet; implanted and non-implanted steers and heifers fed no feed additives; and other diets containing alternatives such as spices and essential oils.

It turns out the conventional diet had the lowest environmental impact. The study also showed that removing growth promotants increased land and water use as well as greenhouse and ammonia emissions.

“There are some within the public that think we should consider removing growth promotants and so we compared the data. And what was really interesting is you’d require a lot more land in production of feed, so your environmental footprint would grow and, likewise, your economic impact,” said Brocklebank.

Arm’s reach

Neither of those projects was done by BCRC itself. Rather, the council works with research institutions across the country (40 so far), including major universities and AAFC research centres. This gives BCRC a wider range of data to work with and pass on to stakeholders.

“What we really focus on is working across provinces,” said Brocklebank. “With some of our forage work, we have researchers spanning across four or five provinces working together. This really excites us because we know they’re working in their own eco-regions and sharing results, but also finding how things might work in other areas as well.”

The peer-review process among academic researchers prevents any industry meddling. Almost all BCRC projects are peer-reviewed, said Brocklebank.

“We go through that scientific process to ensure impartiality so that it’s not perceived as being influenced by industry, although we provide funding,” she said.

“That’s really important for us, and it’s in part why we fund research externally. All of the research is done outside of our organization. We want to ensure we’re funding the right people but it also has to be impartial.”

Areas of interest

The fight against antimicrobial resistance is one of the council’s ongoing research activities.

“We’ve been very aggressive as an industry to develop a strategy around antimicrobial resistance in calves,” said Brocklebank. “A lot of that also has been looking at alternatives to antimicrobials. Are there alternative treatment strategies or opportunities to use things like probiotics or other products to basically reduce the reliance on antimicrobials?”

At a macro level, the beef industry’s goals – such as better feed efficiency – align more often than not with those of the federal government’s, said Brocklebank. Although government mandates lean in the environmental direction, producers’ profit motives frequently cross over through methodology.

“If we can improve pounds-per-day gains and animal health, that increases the number of animals that make it to processing. Ultimately, through that we’re reducing our environmental footprint because that’s measured based on how much less land, water and feed we’re using.

“That’s where I find our goals are very intertwined because a lot of these things are contributing to other outcomes.”

Forage and grassland productivity is another frequent focus for BCRC and its research partners, and such efforts have to account for the diversity of such a large country and its growing conditions.

For a simple example, some areas in the west may need new forage varieties that are drought-resistant, while in the east, flooding may be a bigger concern.

But increased productivity can’t come from varieties alone, said Brocklebank. Management practices also play a key role. That means communicating more management practices to producers across the country. Even in that context, there’s a lot of variability.

“A lot of it’s looking at rotational grazing strategies but then again, what applies in northern versus southern Alberta can be very different, likewise, east to west across Canada.

“So we have forage programs focused on each area of the country specifically and, while results are shared across the country, there is definitely some speciality or specificity.”

As for the future of BCRC, Brocklebank says it will continue to be an intermediary between farmers and government to help farmers.

“We’re being able to trigger governments’ investment needs, but we’ve also launched into extension and supporting Verified Beef Production costs. For me, those programs reach into ensuring research gets into practice.

“It’s fine to fund research, but if it’s not going anywhere, I guess what’s the point? So we really feel like that connection of value.”