Iain Aitken was about two-thirds of the way done calving in the last week of April, but he’d already seen twice the calf losses he’d expect in a full season.

About half of those, he estimated, were direct losses from the weather — the unfortunate legacy of a string of Colorado lows that dropped well over 30 centimetres, and in some places over half a metre, of snow across agricultural Manitoba just as most large commercial cattle operations started calving. The other half, likely to keep hitting over the coming days and weeks, came from the aftermath — the continued cold, mud, and the health issues that come with them.

Read Also

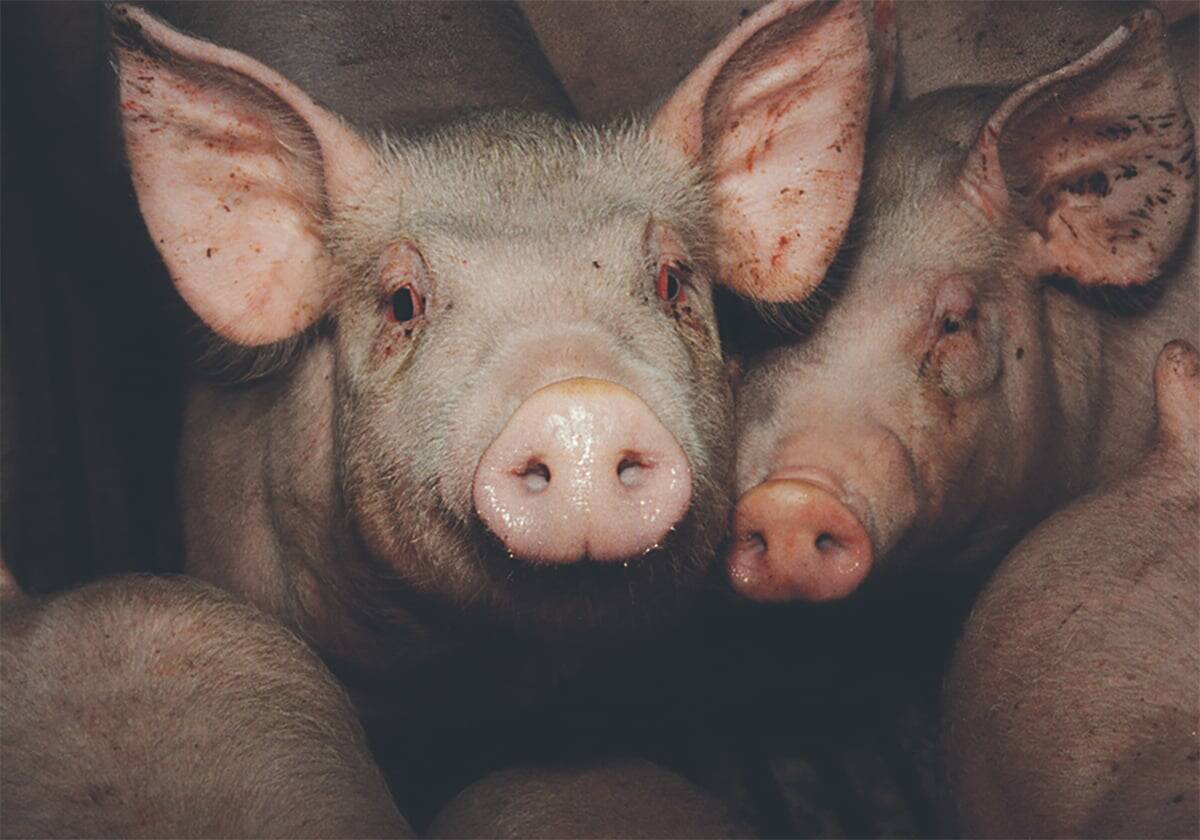

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

A University of Saskatchewan team, through years of research, has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and what hog farmers can do to control it.

“It was kind of unfortunate timing for us because we were just going to start to calve when these storms started,” he said.

“Normally it’s kind of late enough in the year that we expect storms, occasionally, but not a storm that comes and lasts as long (as this),” he added. “It basically lasted a week and it was so cold, we never got rid of any of the snow and then it followed it up with a second storm, which just sort of compounded the issues.”

Why it matters: Manitoba’s second dose of winter hit just as calving started for many large cattle operations, which often do not have the facilities to calve indoors.

The greater losses have also come with an exponential increase in work.

In a typical year, the herd Aitken manages near Belmont would be calving on pasture, with grass banked up from the previous year. This year, however, has been far from typical.

This year, Aitken’s normal calving grounds are buried, he noted, leaving cows to calve inside corrals. Instead of dry ground, he is instead dealing with mud and snow.

“The cows are not getting as much exercise and you get more mild presentations and you have calves that don’t want to suckle, just kind of a combination of things,” he said.

Producers are also dealing with the fallout from the 2021 drought. Conditions last year left producers scraping for winter feed. Straw and forage prices are at a premium. Poor forage and herd requirements led to a glut in auction marts across the province through summer and fall of last year. Producers had already been forced to cull deep coming into fall 2021, including cases of prime breeding stock headed to market.

The 2022 calf crop was expected to be smaller, according to the Manitoba Beef Producers (MBP), while spring has so far provided little respite.

“Losses now will hurt a great deal, as impacts of drought are still being felt,” Carson Callum, MBP general manager, said. “Folks are still dealing with impacts of the drought from a feed availability and herd reduction perspective.”

The spring so far has been, “the final insult after the year we’ve had,” Aitken said.

“The bright side is guys always tend to think that if there’s less calves, then they’ll make more money in the marketplace and hopefully make it up, but that doesn’t always pan out,” he added.

Powerless

Elsewhere in the province, producers in the thick of calving season were left without power for days. As of April 26, Manitoba Hydro was reporting 350 outages (over 200 of which were centred around Dauphin and the surrounding area), following the weekend’s storm. Those challenges were compounded April 25-27, with overnight lows as cold as -16.7 C.

“The fact that there’s snow, yes it helps, because the animals can eat snow, but when it got cold the other night, waterers were freezing because there was no heat to them,” Mary Paziuk, a producer near Dauphin and director with MBP, said. “It definitely changes how you have to work with things… whether or not it increases their losses, it definitely increases their workload.”

The impacts have been variable, she said. Some producers in her area started calving earlier, and thus had older calves when the storms hit. Others, however, were dealing with newborns, and were seeing about twice their normal losses.

Dr. Kevin Steinbachs, co-owner of the Dauphin-Ste. Rose Veterinary Clinic, also noted the continued issues with power, including potential problems with the ability to warm up calves.

He, personally, has not heard of many losses, he said, but noted that many of the producers who would be reporting those issues were still calving, and too busy to talk.

“We have quite a few guys who are just calving big numbers right now, so they might have had 100 calves in the last four days or something like that,” he said. “When it’s mucky and snowy and stuff, they’re not designed for that. That’s the reason they’re calving this time of year, because they don’t have facilities.”

He is, however, concerned about the possibility of health issues like scours and pneumonia further hitting at the calf crop.

“That’ll all just kind of stack on top of everything, because animals are stressed and in tight confines,” he said, noting that many, like Aitken, have been unable to access their normal calving pastures. “Environment’s usually the biggest thing for causing disease and the environment’s not very nice at all right now.”

As of April 26, MBP had got reports of around 1,000 losses, and expected that count to grow.

That number came only days after the organization first put the call out for producers to share loss numbers, in the hopes of gauging the scale of the damage.

“It’s just been one hit after another here,” Callum said. “The timing was very poor for those who calve in the, quote-unquote, springtime — although it doesn’t feel like it right now — when they calve on grass or calve on pasture, these types of storms really have bad impacts.”

He acknowledged, however, that the secondary impacts from having a Colorado low per week for several weeks in a row had yet to be fully felt.

The group expects to take loss information forward to the provincial government, “to see what sort of funding streams or program streams could be developed as a result of this disaster.”