Fetotomy — a veterinarian’s fancy word for cutting up a dead calf within the cow during the birthing process — still has a valuable place in a competent veterinarian’s bag of tricks.

The whole object with a fetotomy is to minimize trauma or damage to the cow. The calf at this point is a lost cause because it has already died. The only times veterinarians do a fetotomy on a live calf include a schistosomas reflexus (inside-out calf) or any other fetal monsters such as a two-headed calf or a hydrocephalus calf (water on the brain). All of these examples are non-viable calves and had they been born alive by C-section would have died shortly thereafter, or been put to sleep humanely.

Read Also

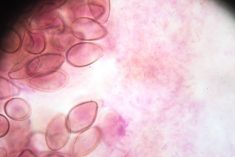

Smart deworming for sheep starts with individual fecal egg counts

Fecal egg count tests are one step to managing dewormer resistance and managing sheep parasites on Canadian sheep farms to maintain flock health.

Fetotomies involve a simple principle. With a specialized instrument (a fetotome) and obstetrical wire the calf is systematically cut into smaller pieces to facilitate delivery out the vagina. The fetotome is generally a two-tubed instrument which protects the wire from damaging the cow. It can be anchored, so to speak, to the calf using an obstetrical chain. This allows an assistant to perform the cut while the veterinarian makes sure of positioning. Our goal as a veterinarian is to minimize the number of cuts, but to do the right ones to expedite delivery. If the health of the cow is maintained, she can often be bred back and go on to further productive years.

The most common usage is for the traditional “hiplocked” calf. As long as the producer has not pulled too hard and the veterinarian can get there quick enough the calf can be split right down the middle of the pelvis. The two halves can then be pulled out by hand, and if the veterinarian is worried about a downer, will probably administer anti-inflammatories.

Another common usage is for a full breech calf with both legs very rigid and manipulation would only lacerate the uterus. Here one must be very confident the calf truly is dead and that can be difficult. The finger in the rectum for sphincter tone is one way, but if a cow has been straining a lot, one can be fooled. The only other way is to reach down and feel the umbilical vessels for signs of a pulse. If there isn’t one, the procedure is the veterinarian will cut off both hind legs and then pull on the stump with a krey hook (we must make absolutely sure there is no pulse). The krey hook is another specialized instrument which looks like an ice pick and as you pull on the chain attached to it, it tightens down into the bone. It generally is best to have it bite into boney tissue like the spine.

Dead, head-first presentations, where the head is a long way outside the vulval lips, is another perfect candidate for a fetotomy. Veterinarians or farmers alike must have to work extremely hard to force the swollen head back inside the now-swollen vagina. Even if you do, by the time both front legs are brought up there may not be enough room. By doing one cut and removing the head and as much of the neck as possible you gain valuable room and most times get the rest of the calf out. A perfect cut here almost dishes out the area between the shoulders making that area smaller as well so a light pull generally extricates the calf.

I have many times told equine veterinarians, “Who better to handle foalings than bovine veterinarians?” Mares seldom have problems foaling, but if they do, it generally is a wreck and if not found and attended to quickly, a dead foal is often the result. I have heard of mares having to be totally anesthetized in order for straining to stop and a head-first presentation pushed back. What better opportunity than to do a fetotomy to minimize damage to the mare. Foals’ extremely long legs make head-first presentation much more difficult in this species. This is where expertise from one specialty (bovine obstetrics) in veterinary medicine can definitely help another (equine).

With emphysematous (dead and blown up with air because they are decomposing) fetuses, if you get the fetus out the back end even with multiple cuts you most often will save the life of the cow or heifer. Doing a C-section is not only very costly and difficult, it is extremely risky. Any contamination from the uterus of its infected contents into the cow’s abdomen will spell almost certain death to the cow.

This is where the skill and experience of the veterinarian really are put to work. With a combination of lots of lubricant to facilitate movement and manipulation combined with the right cuts the calf can often be delivered. If the cuts can expose either the abdomen or thorax, this will allow a lot of the internal gas to escape making delivery easier. When a calf dies, it swells up and dries out the uterus so we are also dealing with an extreme amount of friction when delivering these calves.

Even though it is something a farmer rarely sees, the performance of a fetotomy can be a valuable tool to return the cow to working form. Care must be taken to not damage the cow so her future reproductive function can hopefully be maintained. Generally speaking, with emphysematous fetuses, rebreeding rarely occurs. We rarely perform fetotomies because of today’s easy-calving breeds. But malpresentations, hiplocks, and fetal monsters still happen and we as veterinarians must be able to properly rectify the situation for our clients.