Glacier FarmMedia – There’s a microscopic war raging in your soil, and these bacteria will do whatever it takes to protect and expand their territory.

“It’s like a little arms race that goes on naturally in the environment,” said Reynold Bergen, science director for the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC).

“They’re using antibiotic resistance to defend themselves against each other. Antibiotics are like the swords they use, and antibiotic resistance is the shield,” he said.

“If bacteria are using this to fight each other, we can use them to fight bacterial infections.”

Bergen’s point is twofold: The first is that most antibiotics used in both human and animal medicine are derived from the weapons these bacteria developed to fight each other.

The second is that antimicrobial resistance is also a natural part of this process — which is why there’s a global effort to keep antimicrobial drugs from being overused and becoming ineffective.

Read Also

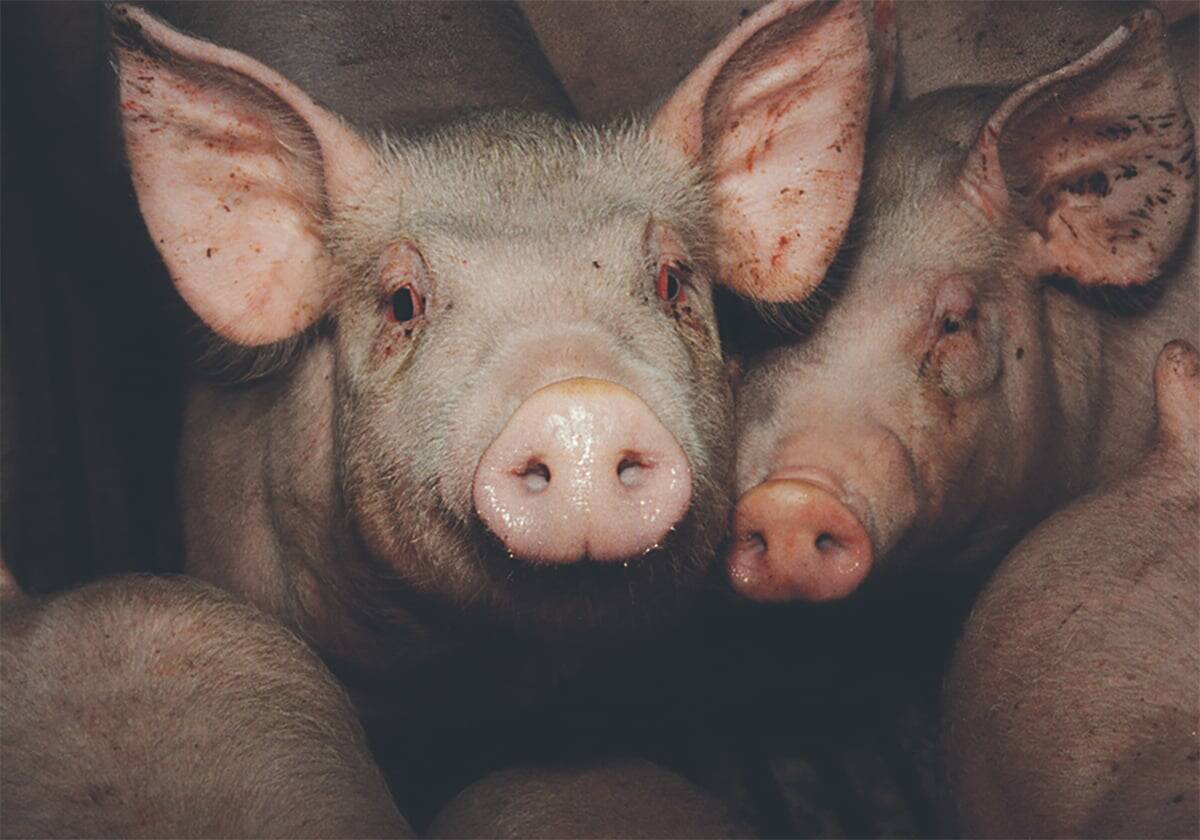

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

A University of Saskatchewan team, through years of research, has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and what hog farmers can do to control it.

“Antibiotic resistance is a big deal,” Bergen said. “Cattle get sick. People get sick too. And when people or animals get sick, we need antibiotics that will effectively treat those illnesses so they get better. And the more you use an antibiotic, the more resistance will develop to it. So we need to be really careful how we use these things.”

The Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance has been monitoring antibiotic use and resistance in all livestock. But its on-farm component has largely been limited to pigs and broiler chickens, as those were the animals considered at highest risk for antibiotic resistance.

But in 2019, a three-year pilot project kicked off to look at antibiotic use and resistance in cattle feedlots, and the preliminary results suggest that antibiotic use in livestock isn’t likely to pose a risk to human health.

“What they saw was, yup, there’s antibiotic resistance in cattle, and yup, there’s antibiotic resistance in people, but the profiles are quite different,” Bergen said.

“The kind of antibiotic resistance you see in cattle is pretty strongly related to the kinds of antibiotics that are used in cattle, and the kind of antibiotic resistance you see in people reflect the kind of antibiotics that are used in human medicine. And they’re quite different.”

Watching for problems

That said, it doesn’t mean resistance to antimicrobials isn’t a concern, he added, pointing to findings from ongoing surveillance of animals at packing plants.

“When we look at samples from sick animals, we see way more antibiotic resistance and multi-drug resistance,” he said. “That’s probably because there are some real go-to drugs for bovine respiratory disease, and when you get resistance to one of those products, you’re pretty likely to get resistance to the others as well.”

“There’s getting to be some challenges, in some cases, getting effective treatment,” he added.

That’s important to feedlot veterinarians like Dr. Joyce Van Donkersgoed.

“If I’ve got resistance to those bugs that can cause pneumonia in cattle — the biggest disease we treat most commonly in the feedlot — I want to know if I have cattle coming in that are already resistant to antibiotics before we even get them into the yard,” said Van Donkersgoed, who is co-ordinating the surveillance program in Canada.

“If that poor treatment response is due to antimicrobial resistance, as veterinarians, we have to look at and maybe adjust our treatment protocols accordingly,” Van Donkersgoed said.

Last month, the surveillance program received $630,000 in funding from Results Driven Agriculture Research (Alberta’s ag research funding agency) to collect data on antimicrobial use and resistance in feedlots across the country (primarily in Alberta). The three years of funding, which will begin next year, will help researchers build on the work that began in feedlot cattle in 2019.

“The whole point of it is to measure trends over time and what’s changing, so the funding will be used to continue collection of antimicrobial use data from feedlots across Canada,” Van Donkersgoed said, adding that, “As an industry, we need to know where we’re at with antimicrobial use and resistance.”

That’s becoming increasingly important as consumers — and hence retailers — focus more on use of antibiotics on livestock.

“When they get concerned that industry isn’t minding its own store, that’s when they start to meddle and impose their own programs,” Bergen said.

“Those sorts of things are a knee-jerk reaction that might sound good until you start to think about it. If animals get sick and you’re not allowed to treat them, that’s not good for animal welfare or for the industry as a whole.”

Too precious to lose

Stewardship is critical because the drug pipeline is pretty much empty.

“It’s unlikely we’re going to get new antimicrobials for use in livestock production, so as an industry, we need to be able to preserve the antimicrobials that we have and make sure that they continue to be efficacious,” Van Donkersgoed said.

Bergen agrees.

“We can”t assume we’re going to get any more tools to deal with animal health issues,” he said.

“If you’re not going to be able to necessarily treat disease as confidently as you used to be able to, then you better focus a bunch more on prevention.”

The first step is vaccination.

“The biggest infectious disease concern when cattle get to the feedlot is bovine respiratory disease, and we’ve got some pretty effective vaccines for those. When they’re stored right and they’re given right and they’re boostered correctly, they work,” he said.

It’s important for calves to get those vaccinations prior to going to the feedlot, to ensure they have immunity before they’re exposed to the disease, he added.

But bovine respiratory disease isn’t just a feedlot issue.

“It’s the No. 1 reason calves get treated on the farm, too,” Bergen said. “So having your vaccination program up to snuff on the farm is going to save you a bunch of hassles as well.”

Proper nutrition, is the next consideration, and just as important as the immune system draws energy to respond to either a vaccine or a disease threat, he added, nothing that testing will be particularly important in a dry year like this one.

And finally, producers should consider stress.

“Stress affects cattle the same way it affects us,” Bergen said. “It suppresses the immune system and the immune response, so it will suppress the effectiveness of vaccinations or the ability of the animal to fight off disease.”

Count the cost

Dealing with the potential fallout from antimicrobial resistance is going to be “way more expensive” than preventing it, so producers and feedlot operators need to do their part, Bergen said.

“If you’re not paying attention and using antibiotics appropriately — or if you’re overusing them — you’re going to get more antibiotic resistance and your drugs aren’t going to work as well,” he warned.

– Jennifer Blair is a reporter with the Alberta Farmer Express. Her article appeared in the Aug. 9, 2021 issue.