The recent cyberattack on JBS, the world’s largest meat-processing company, sends a clear message that agriculture is not immune to cybercrime.

The company paid US$11 million, reportedly to Russian-speaking gang REvil, in the ransomware attack after 13 of its American plants, along with its Brooks, Alta. facility and some in Australia, were forced to temporarily close.

The company processes approximately 23 per cent of the beef in the U.S. and that’s why it paid the ransom quickly.

“The supply chains, logistics and transportation that keep our society moving are especially vulnerable to ransomware, where attacks on choke points can have outsized effects and encourage hasty payments,” cybersecurity expert John Hultquist told Reuters.

In many ways, agriculture and agri-food businesses are ripe for the picking for cybercriminals. Canada’s ag sector is vulnerable because many farms and companies can’t adapt and respond to cyber threats as quickly as those threats are evolving, Cal Corley, the CEO of Community Safety Knowledge Alliance (CSKA) said in a news release.

Earlier this year, the Saskatoon-based non-profit organization was awarded $500,000 from a federal program to assess and promote cybersecurity in Canadian agriculture over the next four years.

“This initiative will help better understand and support the sector in closing critical gaps,” said Corley.

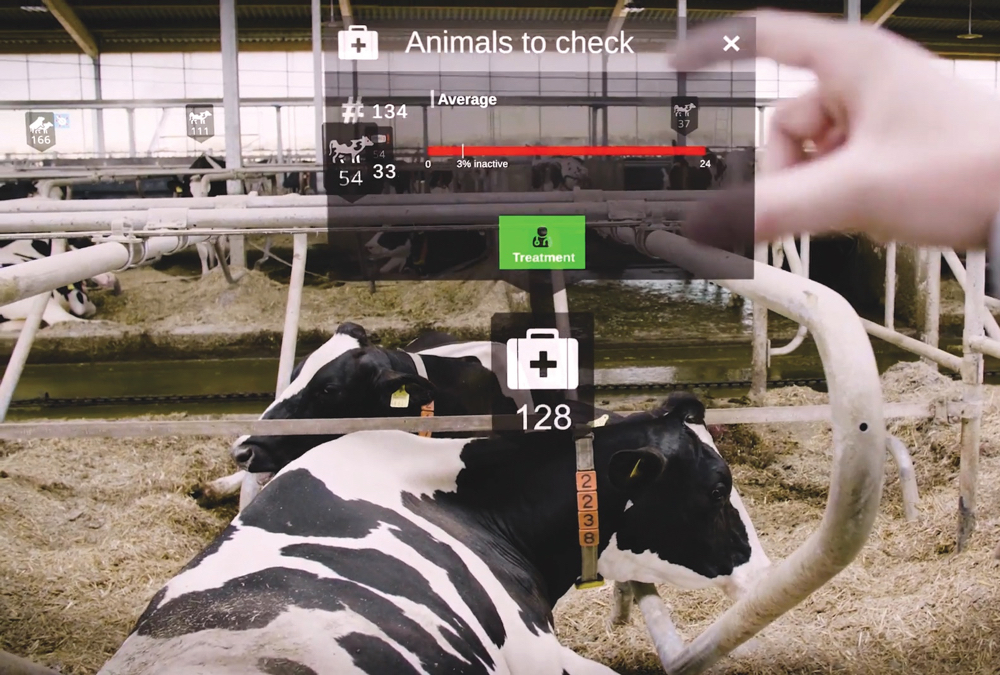

A “rising wave” of digital agriculture — big data, automation, precision and smart farming, blockchain — is revolutionizing how food is produced but also upping cybersecurity risks, CSKA said.

“The impacts of food supply disruptions can extend through the entire agricultural communities to provincial and national economies with potentially cascading costs reaching into billions of dollars and involving collateral damage to social stability,” the organization said.

“If technologies are implemented too quickly without (examining) how the various components fit together within a secure, farm-based cybersystem, the result could be smart farming that isn’t always secure farming,” added Jonas Botschner, lead researcher on the CSKA project.

The organization will be reaching out to farmers and is inviting them to “start thinking about what they want us to know and what they feel they need to know,” he said.

How to protect yourself

There are some simple strategies farmers can employ, said cybersecurity expert Ritesh Kotak.

Small businesses such as farming operations usually can’t afford or access the same type of expertise that big companies can, so being aware that “anything connected to the internet is potentially vulnerable to an attack” is an important first step, said Kotak.

He said he often finds that small-business owners use the same device for corporate and personal purposes, and some even use their personal email address for business transactions.

“Because of that, they are not able to address any issues as they are occurring, and (they are) making themselves more vulnerable.”

Most security breaches are accomplished in low-tech ways, and email is most often the door that cybercriminals enter through, he said.

“I always tell small businesses and individuals the most dangerous thing that you’re going to do today is open email,” he said.

It’s critical for farmers and their staff to be on the lookout for phishing emails. Among Kotak’s tips are:

- Don’t just look at the name of the sender but hover the mouse over the name. For example, an email from John Smith that should be [email protected] may appear as [email protected].

- Look for spelling or grammatical errors and take note if the wording or tone seems unusual. Both are red flags.

- Think twice (or three times) before clicking on a link or an attachment, especially if this is not something the sender normally does.

A low-cost option as an added layer of protection is to have a cloud-based email system, such as Microsoft 365, added Kotak. If a suspicious email is identified, it is quarantined and is unlikely to cause harm.

Understanding what he calls “cyber hygiene” is also key.

The first thing to look at is infrastructure. What software and hardware systems are used? Free software, such as video conferencing apps or file sharing apps, often fill an immediate need (as was seen in the beginning of the pandemic), but these can make a system vulnerable.

Secondly, farmers need to know if their vendors have cybersecurity checks in place.

“Vendors also have a responsibility in this to make sure that their systems are protected,” said Kotak, adding they should be asked how data is stored, who has access to it, and whether it is encrypted and stored in a cloud-based system.

Finally, he advises farmers to ensure they adequately back up their files. This can be as simple as having an external hard drive that should be used daily. Alternatively, people can use a cloud-based program such as Microsoft 365 and ensure files are saved in OneDrive.

Kristy Nudds is a reporter with Farmtario. Her article appeared in the June 14, 2021 issue.