Each year, Ethiopian farmers lose 1.5 billion metric tons of topsoil, Frew Beriso said, quoting the number from a 2008 study.

As a result, whatever investment of nutrients exceedingly expensive for smallholder farmers — are put into the soil are in vain.

Moisture is the other top issue. This year the spring rains are delayed, Beriso told the Co-operator, speaking from his home in Addis Ababa. He heads the Canadian Foodgrains Bank’s agroecology program in the country.

Read Also

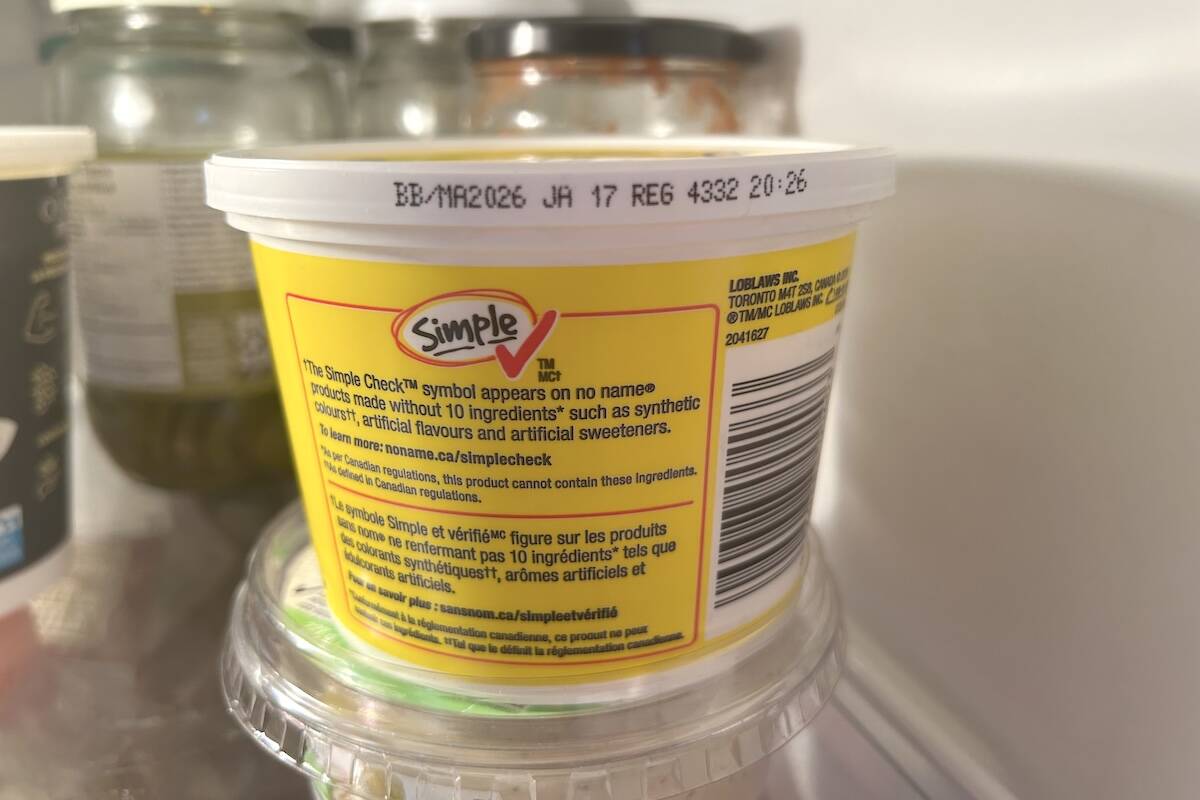

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

The country has two growing seasons, he said — an early, short one where they grow early-maturing crops, and a long season beginning in May when farmers plant major crops like maize and sorghum.

Delayed rains mean the slow-maturing staples may run out of time.

For the last five to 10 years, the seasons have been erratic, Beriso said. He attributed this to climate change.

Between moisture and soil fertility concerns, said Beriso, conservation agriculture is the only hope for a productive farming future in Ethiopia.

“Whether we like it or not, this is the only means.”

Beriso and the Foodgrains Bank have worked for years in East Africa, partnering with local experts and groups to teach the three conservation agriculture pillars: covered soil, reduced tillage and crop rotation.

This January they began a new conservation agriculture program in Ethiopia, building off knowledge gathered from previous work. This time, they have a new, and perhaps unlikely, ally: Norway.

Scaling up feed security

From 2015 to 2020, the Canadian Foodgrains Bank and member groups World Renew, Tearfund Canada and Mennonite Central Committee Canada worked to improve food security through agricultural training in Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania.

The program was called Scaling Up Conservation Agriculture — or SUCA — and was co-funded by the Canadian government.

More than 60,000 farmers trained in conservation agriculture, according to a Canadian Foodgrains Bank report — about 30,000 farmers in Ethiopia, said Theresa Rempel Mulaire, the Foodgrains Bank’s conservation agriculture program manager.

Ethiopian farms are small, family plots — anywhere from one to five acres, she said. Many are run by couples farming together or by women whose husbands are working elsewhere.

The farmers reported 30 per cent increases in soil health after adopting the new farming practices. Crucially, 98 per cent were able to grow enough to feed their families or to make enough money to buy food, said Rempel Mulaire.

Many of these families used to have up to an eight-month food deficit, she said, and many relied on Ethiopia’s public safety net program.

“That’s just how life was in their community,” Rempel Mulaire said of one woman she visited. “That had been part of her life for always.”

This woman’s farmland was poor, and she struggled to raise enough food and to pay school fees for her kids. Her husband had to leave home to find day labour in surrounding towns.

The woman took conservation agriculture training, experimented, and got results, said Rempel Mulaire. Two years later her farm grew enough food for the family and was profitable enough that her husband was able to come home.

The family “graduated” from the public assistance program — in fact, the whole village, which had also embraced conservation agriculture, graduated from the program.

“They were so excited about that,” Rempel Mulaire said.

Experiences like this made the SUCA program take off, said Rempel Mulaire. It contextualized conservation agriculture for other farmers and showed them what it could do.

The Ethiopian government took notice. In 2018, it began to train its extension workers about conservation agriculture principles, Beriso said.

Despite government support, “the mindset is not an overnight issue,” Beriso said.

Not all 70,000, or so, extension workers have been trained. Ethiopian farmers have been farming in the old way — tilling the land to powder — for 1,000 years, he said. Some resist new methods.

The time is ripe for conservation agriculture, Beriso said.

The cost of fertilizer has spiked.

“It’s unaffordable at this time by smallholder farmers,” Beriso said.

Rain is less predictable. Irrigation of the small farms is often impossible. Either water isn’t readily available, or irrigation is cost prohibitive for families farming to feed themselves.

Conservation agriculture techniques can combat these hardships, Beriso said. For instance, keeping the ground cover can preserve crucial moisture so seeds can germinate.

Norway

During the SUCA program, members of the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), a directorate under the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, took notice of the work Foodgrains Bank partners were doing in East Africa.

The Norwegian government was very interested in promoting conservation agriculture, Rempel Mulaire said. It saw the traction Foodgrains Bank partners had gained in Ethiopia and, essentially decided it was more efficient to partner with the Canadian Foodgrains Bank than to create its own program.

Norway is providing $4.25 million through NGO The Development Fund (Utviklingsfondet) for a three-year program to promote conservation agriculture in Ethiopia, according to a March 17 Foodgrains Bank news release.

Work on the program began in January, Beriso said. Program staff are simultaneously developing new programming and training farmers on conservation agriculture practices.

The goal is to reach another 15,000 farmers, but there are millions of farmers in Ethiopia, Rempel Mulaire said. Many struggle with food insecurity.

Conservation agriculture can help farmers escape from poverty, Beriso said.

“What I envision in the coming few years is many more farmers, maybe in the millions, to adopt conservation agriculture and also to improve their food security,” he said.