October 19, 2014 was a warm and sunny day and West Flemish farmer Luc Persyn needed to do a little plowing. Little did he know that would almost kill him. When Persyn first heard the thump beneath his tractor he assumed he’d simply hit a rock, but then the cab slowly began to fill with deadly phosgene gas.

It’s been 100 years since the first bombs – artillery shells, chemical weapons and hand grenades – dropped in battlefields across the Western Front. The most heavily hit region is undoubtedly West Flanders where Persyn lives.

Read Also

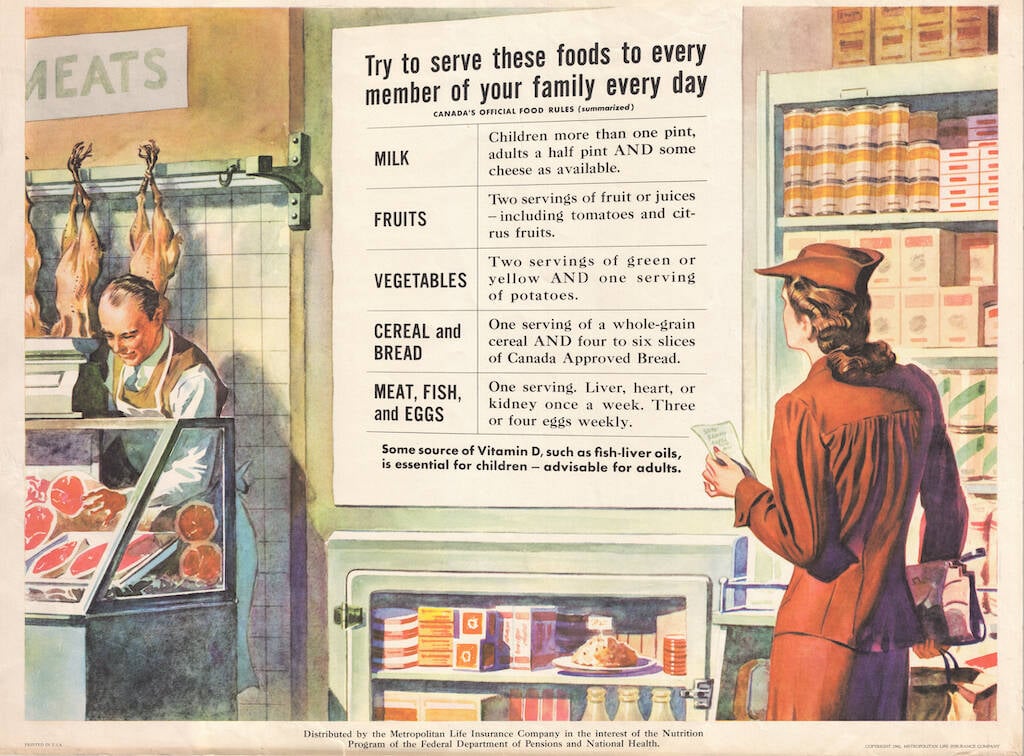

Canada’s ‘Harvest for Victory’ in the Second World War

Propaganda posters celebrating farming show the legacy of Canadian agriculture during the Second World War.

Of the 1.4 billion bombs fired, it’s estimated that some 400 million to 500 million shells did not actually detonate. Of those, experts believe 10 to 15 per cent are chemical weapons, shells filled with toxic chemicals. To this day, those gases – some meant to kill, others meant to confuse or maim – remain, awaiting release.

During the First World War, the Germans and the French were the first to use phosgene gas as a chemical weapon. Persyn’s bomb, however, was of British design. A colourless gas, phosgene has an odour similar to musty hay. To detect it, though, concentration levels need to be 0.4 parts per million. And at that level, it can be deadly.

Immediately after the gas was released, Persyn’s eyes and lungs began to burn. He knew he had to move. If he passed out, it could be hours before someone found him.

Persyn didn’t get away unscathed, though. His lungs and eyes burned, and he said he felt ‘funny’ – not dizzy, but funny. “I immediately felt that I had something in my system,” he said.

Persyn knew he needed medical attention – and fast – but he couldn’t reach his wife, so he called his daughter who works as a nurse in Ypres. She came immediately. He remained at the hospital, where he was put on oxygen, for a day and night. Normal blood oxygen levels are between 95 and 100 per cent, says Persyn. “My blood oxygen level was 88… 75 is deadly.”

Persyn knows he is lucky. Phosgene is highly toxic and meant to kill. Others in the region haven’t been so lucky, though. Unexploded munitions around Ypres have killed a total of 358 people since 1918. Another 535 have been injured.

On the way to the hospital, Persyn called the police to inform them of the bomb. A special Belgian military squad, known as DOVO, is tasked with collecting unexploded munitions in Belgium. They can’t, however, be reached directly. Farmers – for it’s mostly farmers who find the shells – must first call the police, who are trained to identify most bombs.

Depending on urgency, the disposal experts will come almost immediately. Their responsibility is collection; they do not actively search for unexploded shells.

Lieutenant D. Gunst, who works with the special tactical unit in Langemark-Poelkapelle, Belgium, says the army simply isn’t organized to do that.

On average, DOVO receives 3,000 calls a year that lead to the removal of some 300 tonnes of munitions. According to First Sergeant Gaetan Algoet, though, last year they received an incredible 4,025 calls. With a staff of just over 300 – most of whom are not explosive ordnance disposal qualified – it’s a big job.

In Belgium, unexploded munitions are found nearly every day, most commonly between March and May during spring planting, and in the fall during harvest, says Gunst. Since 1918, the squad has identified 90,000 bombs. It’s an ongoing issue with no end in sight. “In my lifetime no one will see the end of the problem,” says Gunst.

In the field, identification is limited to the eye. Once collected, the team takes munitions back to the base and sorts them by hand on an ID platform. It’s not possible to know for certain if some bombs contain chemicals. Those in question are sent to one of two on-site X-ray labs for further identification. Some are dismantled by hand; others are exploded in a contained detonation chamber. At the moment, liquid content shells are safely stored.

Why did so many bombs land but not explode? As the war progressed, explains Gunst, the quality of the shells rapidly deteriorated. In some cases, soil contact was needed for detonation. Often, the soil was simply too wet. Instead of exploding on contact, the shells sunk into muck.

The task of finding the bombs that lie beneath the fields is immense. But what can farmers do? Persyn did look into having his fields professionally cleaned, but he says the cost is too high. Instead, he’s decided to do it himself.

Enter Dr. Marc Van Meirvenne, head of the department of soil management at the University of Ghent. At the exact time that Persyn was being treated in the hospital, Van Meirvenne was knocking on his door. The soil specialist has been mapping heavy metal concentrations (copper, zinc and iron) in West Flanders in an attempt to tie them to First World War munitions. Looking at original First World War aerial photos, he’s been able to determine which West Flemish fields were most heavily hit. Persyn’s farm was on that list.

Using electromagnetic and magnetic detection equipment, Van Meirvenne and his team create maps with GPS co-ordinates for the location of munitions. Today, Persyn is using those maps.

Van Meirvenne feels strongly about the burden unexploded munitions puts on farmers. “All of the risk and all costs remain on the landowner,” he says. “This is not correct because they did not put those shells into the soil, so why should they risk their lives or spend huge amounts of money to clean it?”

“Something must be done because to continue living in an area full of unexploded ammunition, I mean… It’s not a situation that improves,” he said.

For now, though, Persyn has little choice but to do it on his own. Last year, he rented a front-end loader and began work in a recently harvested field.

In the first 10 minutes of work, he discovered an unexploded 90-kilogram British bomb. It took four men to carry it out of the field. Later he discovered a bunker, and nearby, some 200 unexploded shells that had been simply buried at the end of the war. On average, he says he finds 30 shells – 10 unexploded, 20 empty – and 30 hand grenades each year. During potato harvest one year, he found 13 in one day.

It’s a risky task, but Persyn says he’s very careful. “You have to know that we are used to this here,” he says in dialect. “If you dig a hole, there’s a chance you’ll find a bomb. This is how we grew up. This is our soil.”