The invention of agriculture may have allowed for many human advances, but strong bones may not be one of them, say researchers at the University of Cambridge.

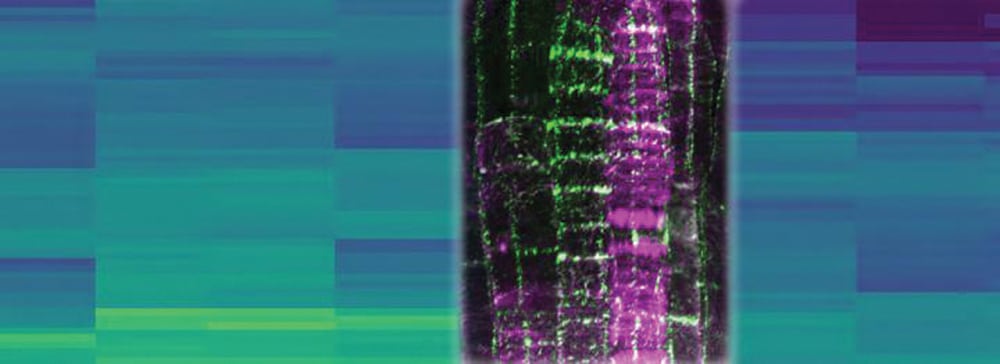

Writing in the journal PNAS, they say that human skeletons have become much lighter and more fragile since the invention of agriculture. Hunter-gatherers from around 7,000 years ago had bones comparable in strength to modern orangutans, but farmers from the same area over 6,000 years later had significantly lighter and weaker bones that would have been more susceptible to breaking.

After ruling out diet differences and changes in body size as possible causes, the researchers concluded that reductions in physical activity are the root cause of degradation in human bone strength across millennia.

Read Also

Meeting of the minds supercharges Canada’s fight to protect antimicrobial drugs

Antibiotic and other antimicrobial resistance could hamstring important medications. One Canadian initiative brings together researchers from across sectors to tackle the problem.

The findings have implications for current health research, as they support the idea that exercise rather than diet is the key to preventing heightened fracture risk and osteoporosis in later life.

“There’s seven million years of hominid evolution geared towards action and physical activity for survival, but it’s only in the last say 50 to 100 years that we’ve been so sedentary — dangerously so,” said co-author Dr. Colin Shaw in a University of Cambridge release.

“Sitting in a car or in front of a desk is not what we have evolved to do.

“The fact is, we’re human, we can be as strong as an orangutan — we’re just not, because we are not challenging our bones with enough loading, predisposing us to have weaker bones so that, as we age, situations arise where bones are breaking when, previously, they would not have,” Shaw said.