Industry criticism of the Canada Grain Act (CGA) tends to portray the legislation as outdated and a bar to improved efficiency, which is grain company code for increased deregulation and privatization of Canada’s grain inspection system.

While the CGA has proven an unreliable defence against reduced regulation, and private inspection has grown apace, accusations that the Act is a fossil are both true and untrue: untrue in that it remains the key defender of producers and grain quality as set out in its mandate; but undeniably true as the Act is indeed old, with the CGA and its predecessors trailing back to pre-1900.

But old doesn’t mean irrelevant or necessarily ineffective. In truth, the CGA is an enduring legacy of the Progressive Era, a popular reform movement that swept North America from the 1880s to early 1920s, seeking improvements in everything from women’s rights, education and public services to workplace standards and banning child labour.

Read Also

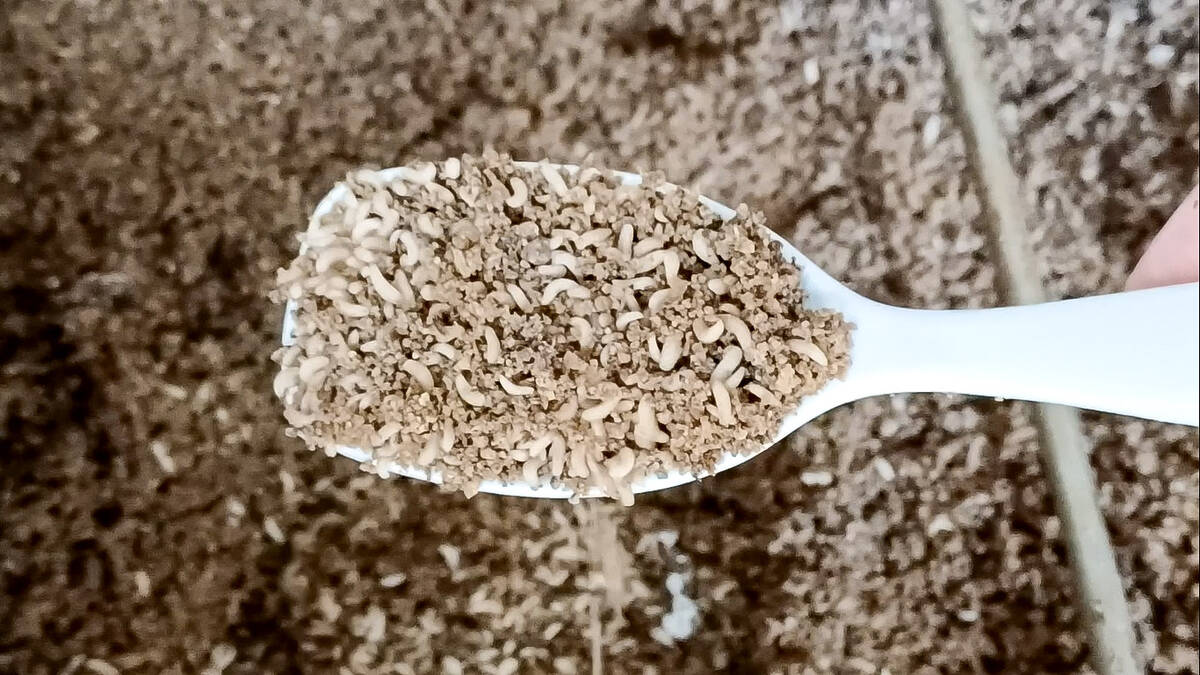

Bug farming has a scaling problem

Why hasn’t bug farming scaled despite huge investment and subsidies? A look at the technical, cost and market realities behind its struggle.

A key focus of Progressive Era reformers was the fight against monopoly, beginning with railroads and the oil industry, but also agriculture, where farmers’ efforts to curb excessive market power – more precisely, oligopoly (few sellers/many buyers) and oligopsony (few buyers/many sellers) – led directly to producer car and other loading rights, creation of the great prairie grain co-operatives, pursuit of a permanent single-desk wheat board and, in 1912, establishment of the Canada Grain Act.

These were huge achievements. Producer car loading acted as a curb on excessive elevation charges, while farmer-owned co-ops controlled more than 50 per cent of handlings and 70 per cent of exports.

Critics notwithstanding, the Canadian Wheat Board minimized, even eliminated, excess basis spreads, negotiated directly with railroads on service and tariffs, and returned all benefits from blending to producers. Meanwhile, the CGA provided a comprehensive system of producer safeguards from country points to terminal elevators.

Today many Progressive Era ideals are enshrined in law. Women enjoy the vote, children attend school instead of work, public utilities replaced rapacious private ones, labour unions are legal. But the age-old problem of unequal market power is with us still – in agriculture in particular. Worse, earlier achievements like farmer-owned grain handling and collective rights associated with the wheat board no longer exist.

Instead, a handful of giant private firms dominate every sector of Canadian farming, from beef and hog slaughter (where two companies, including Cargill, the biggest privately-owned company in the world, kill 90 per cent of fat cattle) through finance to mainline farm equipment. This is equally true of grain where a handful of price-setters dominate chemicals and fertilizer, GMO seed, rail transport and grain handling, again led by Cargill.

Nor has the CGA emerged unscathed. Oversight, once system wide, has been reduced to a short list: licencing, elevator scale certification, producer protection bonding, administration of a dwindling number of producer cars, and the act’s little-used Subject to Inspectors Grade and Dockage binding arbitration provision.

Earlier assistant commissioner oversight, primary and inward inspection, terminal weighing and “weighover” audits, all undertaken in the producer interest, are gone.

Only by chance was proposed legislation diluting the CGA mandate, from regulation in the interest of “producer” – to “industry” – , three times overtaken by election calls in the Harper years.

In 2022, the Canada Grain Act is all that’s left of farmers’ heroic historic efforts to build and codify grain producers’ rights in Canadian law. What remains of the CGA is not only important, it’s the only statutory protection farmers have outside the courts.

But just like the Progressive Era, reforms are urgently needed to expand Canadian Grain Commission (CGC) scrutiny of grades, weights, dockage and instruments at primary elevators, and restore the itinerant assistant commissioner role in the country.

Fortunately, most can be achieved without legislative change. Farmers are fortunate also that for the first time in years, CGC commissioners all come from the producer or farm organization side. Moreover, the ancient practice of patronage appointments (by all governments) has ended, with most recent appointments made following an open request for submissions and solely on merit.

If critics of the CGA really want to break new ground, they should consider utilizing the act to enforce equitable, uniform standards in farmer grain contracts. Now that would be a real Progressive Era-worthy achievement! And one completely in accord with producers’ age-old efforts to combat excessive industry market power through the Canada Grain Act.

Bruce Dodds is a long-time farm organizer who has worked with the Agricultural Producers Association of Saskatchewan and the Hudson Bay Route Association, among others.