A project on two Saskatchewan First Nations seeks to restore community members’ relationships with the land, water and sky, and to reimagine their relationships with neighbouring farmers.

A big objective of the Bridge to Land Water Sky Living Lab is to see lease agreements with farmers as not just financial transactions, but “promises to each other and the land,” Melissa Arcand said during a University of Manitoba webinar March 8.

Why it matters: An Indigenous-led Living Lab hopes to recover their communities’ connection with the landscape and agriculture and ultimately see gains in food sovereignty and economic prosperity.

Read Also

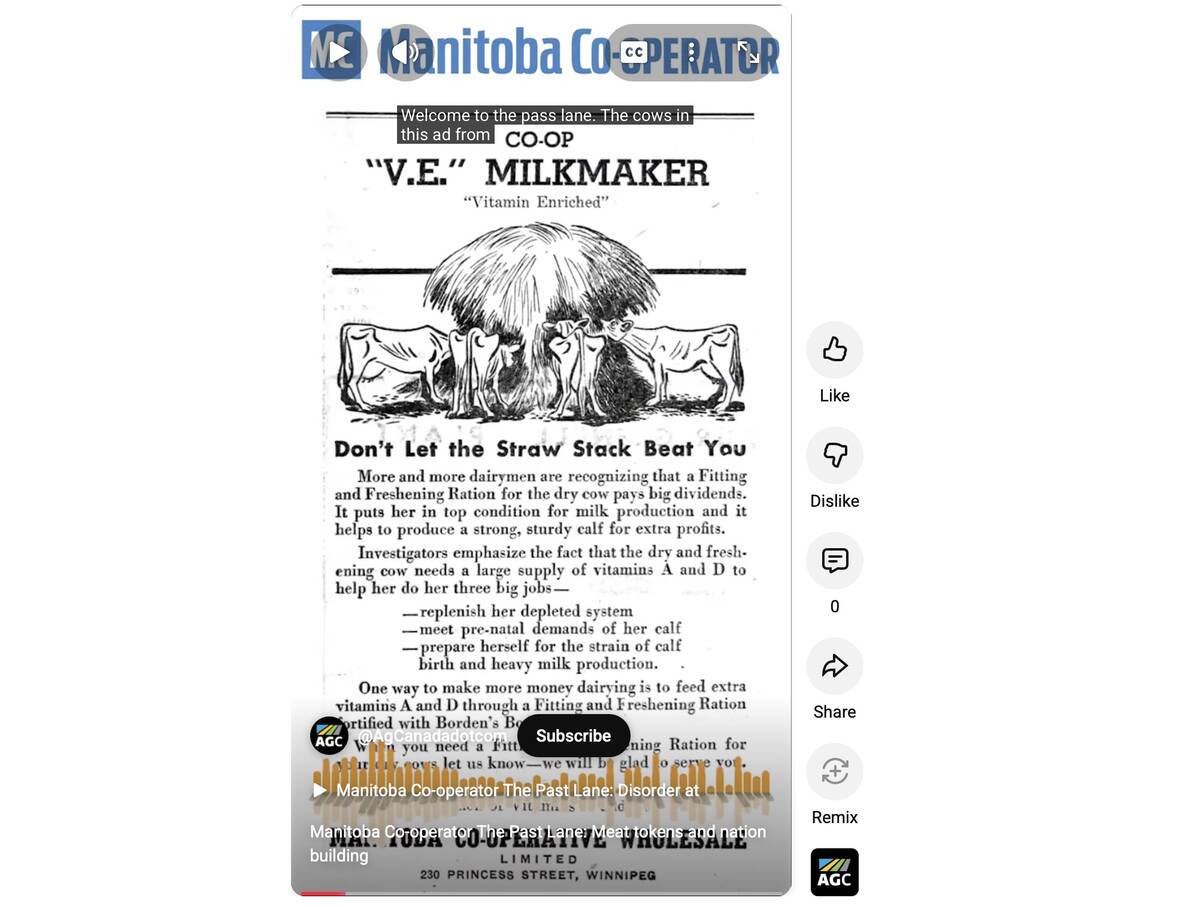

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

Arcand is member of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation near Prince Albert, Sask., and an associate professor in soil science at the University of Saskatchewan.

Muskeg Lake has partnered with the neighbouring community of Mistawasis Nêhiyawak and other organizations to lead a five-year program, funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

The Living Labs Initiative is a federally supported group of projects in various provinces, all mandated to connect farmers, industry, researchers, and other partners to develop and test innovations and address agro-environmental concerns.

In this case, the Living Labs program tests and monitors beneficial management practices and technology on-farm and elsewhere on the land. It is the first Indigenous-led Living Lab, according to an article posted on the Mistawasis Nêhiyawak website.

Launched in fall 2022, the project will work toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions and strengthening climate resilience. However, its goals also extends to increasing food security, boosting the regional economy and restoring relationships with the land, Arcand said.

The communities have long histories of farming. Anthony Johnston, a special advisor with Mistawasis Nêhiyawak, pointed to both his grandfathers, who he says were both successful farmers. They had intimate relationships with the land, he said, and knew what would and wouldn’t work.

However, farming declined among First Nations members for several reasons. Farmers faced restrictions under the Indian Act, including when and how they could sell produce. In the 1910s, both First Nations involved with the project lost most of their Class 1 agricultural land, and some Class 2 land to government expropriation. Mistawasis Nêhiyawak lost 18,000 acres and Muskeg Lake lost over 8,000 acres, Arcand and Johnston said.

Much of the remaining land is marginal and at more risk of soil degradation and carbon loss, Arcand added. A lot are fallow.

Though some residents farm, the majority of their remaining agricultural land is leased to non-First Nations farmers—generally in three-year terms, according to Arcand. These short terms have disincentivized some best management practices, she said. And while BMPs can be built into lease agreements, these have proven hard to monitor or enforce.

Community members became increasingly concerned about the land and water and the health of the people and animals living on it over time.

Bridge to Land Water Sky plans to tackle these concerns through six “big activities,” Arcand said.

These are:

- Engagement and relationship-building with farmers, youth and stakeholders

- Taking inventory of and mapping agricultural lands on the reserves

- Using “bundles of BMPs” to enhance crop land

- Restoring marginal lands “to regenerate grasslands and grazing land and forest”

- The collection of biophysical and socioeconomic data

- Training, demonstration and education

The project wants to support biodiversity and water conservation, and to create employment and learning opportunities for people on and off reserve.

The two leaseholders farming on the First Nations are among the largest farmers on the Prairies, Johnston said. One of those farms began with a quarter of Mistawasis Nêhiyawak land.

“That could’ve been us,” Johnston said.

“Our Bridge to Land Water Sky is our expression of hope to join the larger economy, including the agricultural economy,” he said.

The question becomes, what do community residents want? Do they want to be big producers? Or do they want a return to mixed family farms blended with hunting and harvesting of wild foods? The communities have space, for example, to experiment with alternative crops that could support one or two families on smaller plots of land.

Mistawasis Nêhiyawak also plans to return buffalo to their acres, Johnston said. Some young community members will be working to steward a bison herd in the Prince Albert National Park through the Buffalo Trace program. That program may yet work with the Bridge to Land Water Sky Program. The young people will gain the skills and knowledge for when the community is ready for their own herd, Johnson said.

“The bridge is about relationships between people,” he said. “The bridge is also about relationships, a return to great relationships with land, water and sky. So, our bridge is a bridge of hope.”