Wayne and Trena Zacharias have bet the farm on haskap berries.

The couple has already sunk nearly a quarter-million dollars (excluding land value) into their switch from grain farmers to proprietors of a 20-acre berry orchard near West St. Paul. It’s cost them almost two years, buckets of sweat and the anxiety of getting young plants through their first full season amid a raging drought.

Now, the plants at Haskap Berry Orchard are finally starting to bear fruit.

Read Also

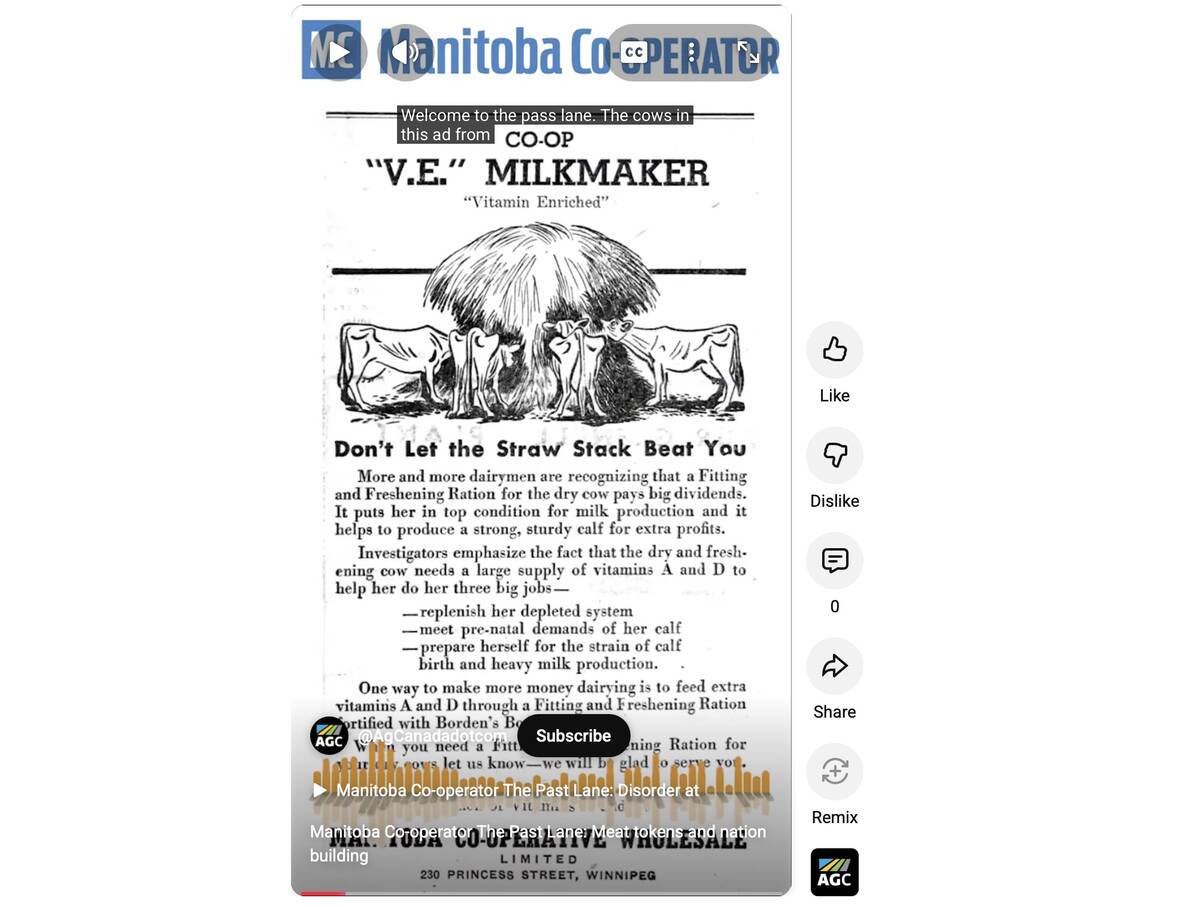

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

Why it matters: The 20-acre orchard is still getting its feet wet, but promises to be the biggest haskap-producing operation in Manitoba once plants mature.

The haskap berry took its name from the Ainu people of northern Japan and has long been popular in that country and in Russia. Its high antioxidant rating has gotten it pegged as a “superfood.”

Otherwise known as “sweet berry honeysuckle” or “honeyberry,” the plant species is native to Canada — along with most of the Northern Hemisphere — although native cultivars would not be on most people’s short list for wild picking. Berries from those plants are only a little larger than a grain of rice, and aren’t very tasty.

Until recently, no one cultivated the plant for its berries in Canada. That started to shift after research in the early 2000s at the University of Saskatchewan, spearheaded by the institution’s fruit program head, Bob Bors. He gathered seed from Japanese, Russian and Polish varieties in hopes of creating a bigger and more palatable hybrid. The end result was a sweet, large, almost cylindrical berry with a taste often described as a cross between blueberry and raspberry.

By the early 2010s, haskaps had begun to gain a foothold. According to an overview of the domestic fruit sector, released by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in 2021, about 1,720 acres of haskap berries were in play as of 2020, a slow climb from 2018 (1,380 acres), the first year the overview included data for the crop.

But despite growing conditions favourable to the species, Manitoba has been late to the party. According to Philip Ronald, who runs Riverbend Orchards near Portage la Prairie, Man., Alberta and Saskatchewan boast hundreds of acres of haskap berries. In Manitoba, outside of Ronald’s own eight acres and the Zacharias’ operation, there are only a handful of growers. Of those, most are small and many have less than an acre.

Switching it up

Before embarking on the path to berry production, Wayne Zacharias knew a lot about grain. The third-generation farmer had set down roots near Plum Coulee in south central Manitoba, having previously been hired for custom seeding work in the area. He eventually leased land in the region and, for the next several years, worked that parcel along with his father.

Then, tragedy struck.

“My father passed away field spraying by the power lines over there,” he said, pointing to a line of hydro towers about 500 metres away.

Zacharias was hit hard by his father’s death. The loss made him consider leaving the industry, although he ultimately decided to stick with the farm after meeting his wife. But misfortune wasn’t done with the couple. In 2019, their harvest was devastated by an early Thanksgiving-weekend blizzard. That storm dropped heavy snow across the province and was the first in a string of poorly timed precipitation events. Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation later estimated that just over 417,000 of the province’s acres did not get harvested that fall.

“We had a disastrous year in 2019 and we ended up harvesting only 70 or 80 per cent of the crop here,” Wayne Zacharias said.

The disappointing harvest was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and the couple decided to abandon grain farming and look for alternatives.

Their next step came from a houseguest. The friend, who was working toward a doctorate in urban and economic development, had just finished a research report on a saskatoon orchard. She suggested they explore a future in that crop.

While researching orchards and saskatoons online, Trena Zacharias came across an article on haskap berries.

“I had never heard of them, so I started researching and reading about them,” she said.

She discovered that the University of Saskatchewan had scheduled an information session for potential growers.

“So, I got in the car, drove down to Saskatoon, attended ‘Haskap Days’ and learned all about the haskap berry,” she said. “I taste-tested about 20 different varieties there. I picked my top five and that’s what we have here now.”

The next step was to find a parcel of land to establish an orchard. The couple visited several sites before choosing their current location.

“We knew about this parcel of land here because I farmed right around it for a number of years and it hadn’t been cropped for 20-some years. It was just hay and slough,” Wayne Zacharias said.

It wasn’t the most productive land, but it’s actually ideal for haskap. The land had been dormant and untouched by pesticides, herbicides or chemical fertilizers, making it perfect for the organic certification the farm hopes to secure.

The summer of 2020 was spent draining and preparing the future orchard. That fall, 20,000 seedlings went into the ground.

The celebration was short-lived.

The winter of 2020 was noted for its lack of snowfall, leading into what would become one of the province’s worst droughts since the 1980s.

In some cases, haskap growers might expect fields to produce half a pound per plant in the first year. The Zacharias farm was not so lucky. Dry, hot conditions in 2021 put a strain on plants. Much of the province saw little to no rain in June and July and the season was a bust.

“Last year was a total loss,” Trena Zacharias said. “We were watering every day, all day. We were doing everything we could to just keep them alive.”

After all they’d been through, the plants’ lack of progress was disappointing.

Brighter times

Fortunately, the haskap is hardy. The plants in the orchard appear to be bouncing back and, while this year’s crop wasn’t large enough to generate revenue, they expect to get to the half-a-pound-per-plant level by next year. By the time bushes reach full potential (around three to five years), those production numbers should jump to seven to 10 pounds of fruit per plant.

By next year, the farm should start more typical operations. The couple has plans to set up U-pick services at the orchard to help recoup the investment. As production grows, the couple plans to buy a harvester.

In addition to supplying food manufacturers and U-pick customers, they can also grow and sell plants to the public. The University of Saskatchewan has awarded Haskap Prairie Orchards one of 17 propagating licences in Canada.

“We are extremely fortunate that the university saw our commitment to their haskap varieties and awarded us this privilege,” Trena Zacharias said.

They are also trying to spread the word. The tricky part about marketing any new food product is ensuring production doesn’t outpace demand.

“We’re getting in touch with a lot of people that are showing a lot of interest locally here in Winnipeg,” Wayne Zacharias said.

Those discussions include talks with an ice cream maker interested in making haskap ice cream. The farm is also considering whether haskap juice is an option, while co-ops, and their push for locally grown produce, are another potential market.

“We’re hoping they will have an interest, and I think they probably will,” he added.