Glacier FarmMedia – It’s not for everyone, but raising grass-fed beef can bring returns that conventional cow-calf producers can only dream about.

“Someone can make a living off 70 head of grass-fed beef easily — or even 50,” said Ben Campbell, who raises both grass-fed and conventional cattle near Black Diamond, Alta.

“Where if you produce 50 calves a year in a cow-calf operation, you wouldn’t have a chance.”

But you would have a more relaxed lifestyle.

“We get phone calls every day of the year except for Christmas Day,” said Campbell. “There are fussy customers and nice customers (but) it’s a whole other totally different skill set and different than beef production and farming.”

His definition of grass-fed beef is that it comes from cattle raised “on some sort of grass diet, not in a feedlot and usually out in the open.”

Tim Hoven prefers to refer to his cattle as grass finished, since the cattle on his certified-organic operation near Eckville never eat grain at any point in their lives. He’s been doing this for 20 years and has a clear goal when it comes to breeding.

“We’ve been working hard to fine-tune our genetics so animals perform well in our microclimate, under my management,” said Hoven, who calves out about 160 head a year. “Any cow that is a bigger-frame cow that gives me a calf that takes longer to finish is going to town.”

Because of that consistent culling, his animals have smaller frames.

“The smaller heifers, some of them can be done in 20 to 21 months. Some of the bigger-framed steers can take up to 36 to 37 months. Our daily gain is rarely over two pounds a day. On a bigger frame, it takes a lot to get them up to that finished weight.”

Read Also

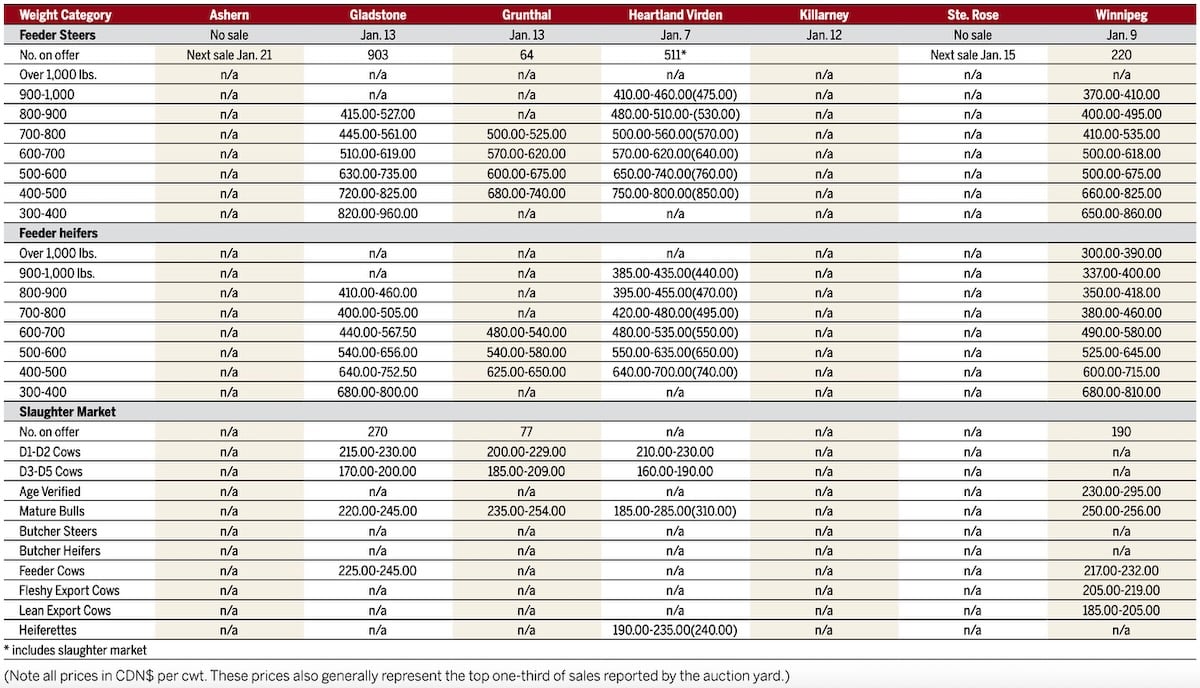

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 15

For Campbell, it’s 24 to 30 months — versus around 18 months for conventional cows finished on grain.

“The main cost is not finishing them. In conventional cattle, finishing them is when they have a high-grain diet, and grain is a lot more expensive than grass,” he said. “The fact that you have to overwinter them for two winters instead of one is the main thing.”

You can shorten that period but you get a different product, he added.

“Some people grass finish beef after only a year and a half, and they only maintain animals for over a winter,” said Campbell. “Depending on how fat you want them, you can get lean grass-finished beef that is overwintered one winter. There’s nothing wrong with them. It’s just lean.”

Lean beef isn’t popular everywhere, but people seem to like it in Ontario and in Vancouver, he added.

Breeds don’t matter a lot — in the grass-fed game, it’s all about size.

“Big animals take a long time to finish and need a lot of energy,” he said. “The smaller-framed animals will finish earlier in life, and they will fatten up a lot earlier.”

The sales side

But while there are a lot of people willing to pay a premium for grass-fed or grass-finished beef, the money doesn’t just magically appear — marketing is the most important component.

“That’s where all the value is in being a grass-fed producer,” said Campbell.

He said there is an option to sell to grocery delivery companies, but those options only offer a small premium above regular commodity beef.

“All the power and all the value is in marketing and selling the beef to consumers and delivering the beef,” he said.

But while direct marketing has high margins, it is labour intensive.

Still, it was what gave Campbell — who began with a small number of cattle and rented land — a chance to build his operation. Because of increased demand at the start of the pandemic, he and wife Steph produced 82 grass-fed cattle in 2020. But that was so much work, they scaled back and increased their commodity beef herd and are currently raising 275 conventional cattle, and 25 grass finished.

Hoven’s sales all come through his website. He owned a butcher shop in Calgary for 15 years, but got out of that so he could focus on direct-to-customer sales. He currently uses a local processor to butcher the meat, and does deliveries in Calgary, Red Deer and Edmonton.

The biggest challenge is that he and his family have to do everything, from calving and taking animals to slaughter to marketing and distribution.

“There are no existing channels for doing this. Everything we do, we have to invent,” he said. “It’s extremely time consuming. But there are benefits to that, because I can control everything and I know how everything is done.”

The second challenge is finding kill space because it’s hard to book small processors right now.

“We’re trying to slowly expand, and we’re always looking for different options to increase that kill space,” he said.

But there’s a solid future for this type of cattle production.

“The customer interest in grass-finished beef is slowly and steadily increasing,” said Hoven. “I don’t know if it will ever be a mass-market item.

“(But) for the people who want it, they are 100 per cent dedicated to eating it. And paying a premium because they know how much more it takes to produce.”

– Alexis Kienlen is a reporter for the Alberta Farmer Express. Her article appeared in the Jan. 10, 2022, issue.