Herbicides have been the No. 1 weapon against weeds since the 1940s.

They’ve been effective but the last few decades have shown that genetics are a more powerful force than chemistry.

Weeds are gaining genetic resistance to herbicides faster than new chemistries can be developed.

Read Also

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

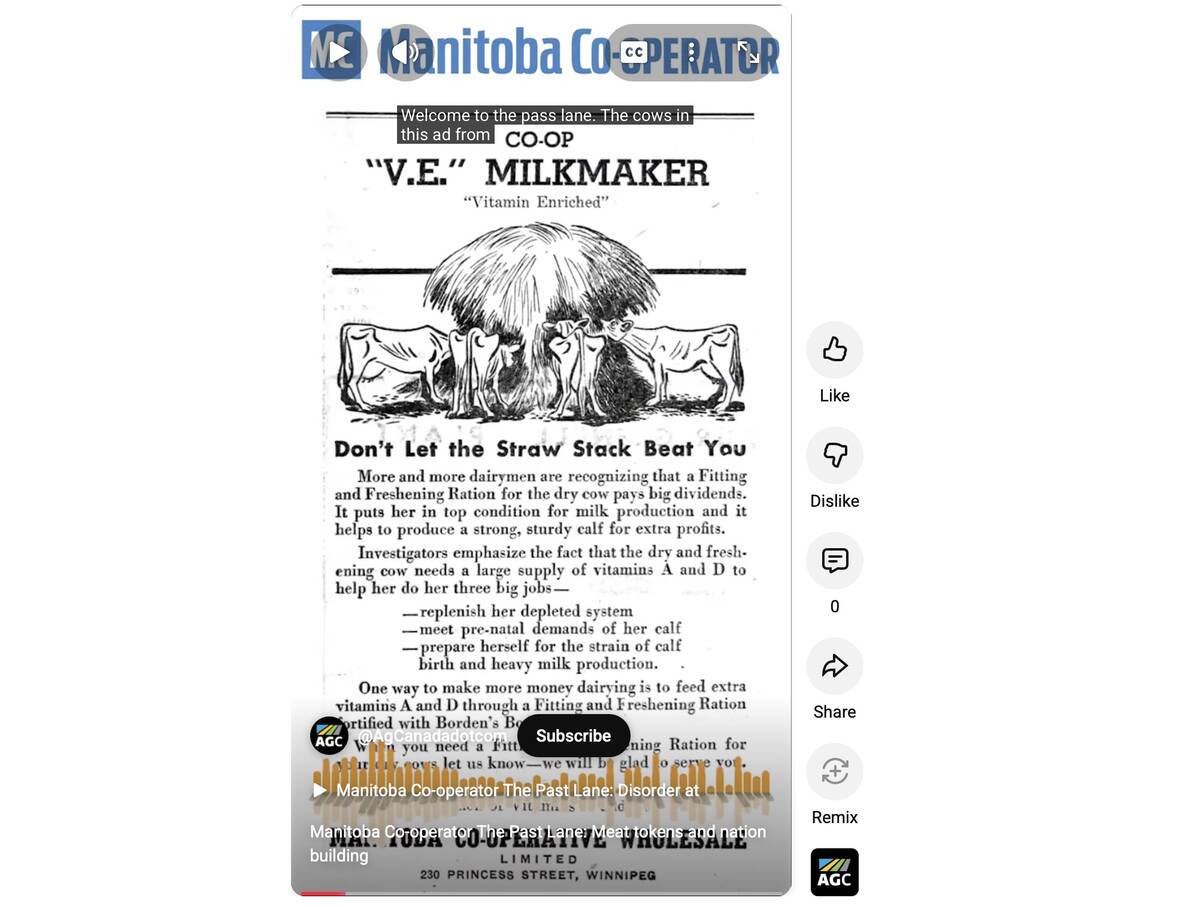

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

“In addition to all of these new cases we’re seeing, the ones that we already had are becoming more common, they’re taking up more area, they’re becoming more frequent.” says Agriculture and Agrifood Canada weed scientist Breanne Tidemann. “So we really need to be looking at non herbicide management tactics.”

The overall strategy is to stop using a single approach, like herbicides, and start integrating several different tactics such as cultural, mechanical and high tech to manage weeds.

A multi-pronged approach hits weeds from several different directions and puts them on the genetic back foot, she told this winter’s Manitoba Agronomists’ Conference.

“They’ll develop resistance to any strategy that you put out because it is a selection pressure and weeds are fickle,” Tidemann says.

“So what I’m saying is let’s not focus on the chemical part of the weed management program and forget about everything else. Let’s actually use all those other techniques together to manage our weeds.”

On the cultural front, Tidemann’s predecessor, Neil Harker, looked at wild oat populations in barley plots. He examined three tactics: doubling the plot density, using a taller and more competitive strain of barley, and running four years of barley in the plot instead of rotating to other crops. Each tactic reduced wild oat populations on its own but the greatest reductions occurred in combination.

“If you did all three, it reduced the wild oat biomass by 19-fold.” Tidemann says.

Harker also found that once wild oats were on the ropes, they could be knocked out by changing the rotation to a winter cereal.

A single knockout punch from herbicides will work in the short term but weeds will learn how to dodge the haymaker, so growers still need to know the footwork and the combinations.

That doesn’t mean farmers should forsake herbicides. It means they must play a more complex game based on weed behaviour.

Tidemann served up other ways to deal with weeds. The holy grail is to keep seeds out of the soil where they can lie dormant until an opportunity presents itself.

“One of my soap boxes or passions is harvest weed seed control,” Tidemann says. “It’s a new paradigm of weed control that’s been developed and refined in Australia.”

Australia’s weed control game changed when ryegrass became glyphosate resistant. The answer was to target the weed’s seed head and destroy it before it hit the ground. Inventors developed the Harrington Seed Destructor, a hammer mill towed behind the combine that pulverizes weed seeds.

The new generation of seed mills are much smaller and installed directly onto the chaff spreader. They are effective but not cheap. The company website lists them from AU$84,000.

“There is also narrow windrow burning,” Tidemann says. “That’s all the straw and the chaff dropped together in a line. (Australian farmers) would do this on every pass and then go out and burn each of these.”

Other methods of harvest weed seed control include baling the chaff and removing it from the field or collecting it in a wagon towed behind the combine and either burning it or using it as animal fodder.

There are other simple technologies. The Weedclipper from Bourgault Tillage Tools is a 50-foot boom towed behind a tractor. It looks almost like a sprayer but instead of nozzles it has small mower blades that clip the tops off the weeds.

“It’s essentially a mower that they’ve just set up so that you can raise it above your crop height.” Tidemann said. “That prevents those weed seeds from being produced and gets them out of the field before they’re going into the seed bank.”

In parts of Ontario, farmers are electrocuting weeds by using electrodes mounted on the front of tractor. It works well in soybeans and lentils, where the crop stays relatively short and producers might see weeds early on.

“Electrical weeding seems to be really good on tall broadleafs but it seems to be less effective on grasses,” Tidemann says. “You can hit that main stem but you’re not getting the tillers of the grasses or the branches of the grasses.”

Some are using lasers, an economical method for high-value horticulture crops.

“This one is really interesting because it lasers the weed meristem so it’s got a fairly high rate of not having those weeds grow back after it’s been lasered,” Tidemann says.

“I do have significant concerns about using this in no-till conditions when you’re firing a high-powered laser when there is really dry crop residue around. I have fears of a big fire.”

Then there is the burgeoning field of farm robotics and prototypes that use artificial intelligence with different search algorithms for different crops. They’re mostly used in greenhouses or in horticulture but field tests are going on in Ontario with Quebec’s Nexus Robotics La Chevre, The Goat.

“This one is fully autonomous, and they are continuing to do field testing, primarily in horticulture crops in Ontario, in the next couple of years,” Tidemann says. “I love how it’s little ‘fingers’ go out and pull the weed.”

All these technologies, including herbicides, are aimed at weed control. Each is effective but not by itself.

Weed control is a genetic game and pest plants have been playing it well enough to survive for much longer than humanity has been farming. There are no single knockout punches. Farmers have to develop the combinations that are hard for weeds to defend.