Midway through 2021, the Manitoba cattle industry faced its toughest stress test in decades as drought extended throughout the Prairies and threatened the livelihood of cattle producers.

“It was very difficult to deal with all the facets of a drought. It really stressed individual producers. It stressed our resources to be able to deal with them. It stressed the industry organizations and the capacity to advocate for all of the issues and listen,” said Tyler Fulton, who was elected as president of Manitoba Beef Producers in February, replacing Dianne Riding.

Read Also

Wheat prices likely headed for sideways trade

U.S. brush with a severe winter storm put only brief upward pressure on wheat futures markets into last week of January.

“I started raising cattle right around (the BSE crisis)… It was a major challenge, but within a short period of time, you started to see a pathway that we could get back to some sort of market level,” he said. “The nature of a natural disaster is such that you can’t point to when things will normalize.”

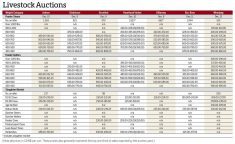

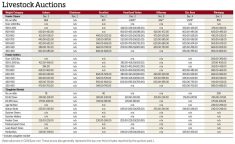

The lingering drought forced producers to sell parts of, if not their entire, herds, causing cattle auction sites to end their summer break in August. Feed grain production in the Prairies was also sharply cut, prompting feedlots to purchase more imports from the United States and governments to encourage alternative uses for sun-baked crops.

Also in August, it was announced that $155 million would be earmarked — $62 million from the province, $93 million from the federal government — toward programs under the AgriRecovery framework. However, rains in late summer and early fall improved pasture conditions in certain areas, causing a slowdown in sales. As of Oct. 22, the province reported only 118 AgriRecovery applications, totalling $1.67 million.

“We still don’t really know (how much the damage cost). We know that marketings of bred cows that came from a lot of the ranches and farms that were affected are still ongoing because the feed in order to secure their places on the farm over the winter (was not there), or the feed was so pricey,” Fulton said. “Unfortunately, we know the herd is going to take a hit this year because of the conditions.”

Effects from the 2021 drought only served to compound already existing effects from COVID-19. The year began with backlogs forming at the Cargill meat-processing plant in Guelph after a two-week shutdown in December 2020. More meat-processing plants in Canada and the U.S. also suffered COVID-related labour shortages and shutdowns during the year.

The potential for strike action at the Cargill plant in High River, Alta., which processes one-third of Canada’s beef and was the site of a large COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, lingered for most of the year before employees approved a new contract in December 2021.

Locally, a fire destroyed the facility for Pipestone Livestock Sales, 35 km south of Virden, forcing cattle sellers to look elsewhere.

‘Not much profit’

Brian Perillat, manager and senior analyst at Calgary-based market information firm Canfax, said calf prices took a hit going into the fall run, dropping to some of the lowest levels seen over the past decade. While consumers were paying record-high prices for beef at the grocery store and cattle prices in Western Canada were the strongest in North America, there was little for profit.

“(Prices were) a bit disappointing overall, just given how strong demand was on the beef side and how strong beef prices have been,” he said, adding that feed cattle prices remained strong throughout the year, but still below beef prices.

“As we ended the year, fed cattle prices have strengthened quite a bit. Realistically, we have some of the strongest prices since 2014. But there’s not really much profit,” he said. “The bottom line is producers are not positive (in profit margins) or just barely positive.”

Calf prices averaged close to those in 2020 before the fall run, he noted, elevated due to high feed costs (up to $400 per tonne) with a 550-lb. steer calf raking in $2.25/lb. According to Perillat, Canada also became a net importer of feeder cattle during the year, with 250,000 head coming north from the U.S., resulting in the largest domestic slaughter in 15 years.

“As we got into the second half (of 2021) with the drought and high feed costs, we moved to a fairly big discount. We saw demand fall back a little bit,” he said, but shrinking herds and high demand may result in higher prices in 2022.

“We’ve got record beef production in Canada and the U.S. combined. To see wholesale beef prices hit these kinds of record-high prices was phenomenal on the demand side… The value of our exports are up 40 per cent, to well over $4 billion of exports. The demand picture is a highlight, but cattle producers may not be excited because they didn’t see (as) much of the price increase as the rest of the supply chain.”

Fulton said the highlight for him in 2021 was seeing examples of producers helping each other out, whether it was providing water for neighbouring herds or hay growers in the Maritimes donating surplus crops.

With soil moisture already lower than normal at many places across Manitoba, the potential for another drought remains strong for 2022. While Fulton says the industry has become “downtrodden,” it will remain steadfast in the face of what’s to come next.

“Cattle producers are a resilient bunch. We really figure out ways to get by, to make it work. It’s not sustainable in the long run, but I think we’ll be OK in the long run,” he said. “In general, I’m optimistic about the industry’s potential… but we’re all hoping for more moisture and more rain this coming year.”