“Never forget this – it’s a pennies business,” Keystone Processors president Kelly Penner said last week following

the new beef-packing company’s official opening in the former Schneider’s pork plant on Marion St. in Winnipeg.

It’s also a business in which new players need to watch their backs.

As one industry participant put it recently, the recent mergers

between large players in the sector haven’t taken place because they were making lots of money as stand-alone operations. The big packers are bleeding due to overcapacity and their inability to source cattle against stronger U. S. prices, as well as ongoing labour shortages.

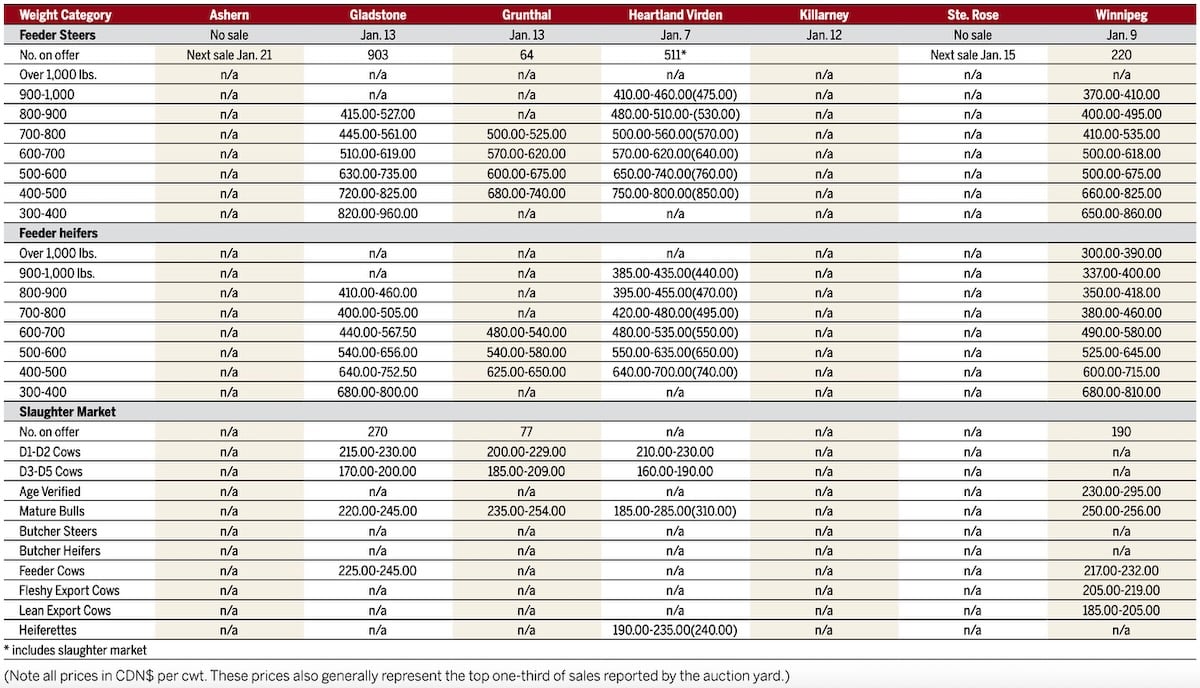

Read Also

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 15

They understandably don’t want to see more competition, even competition that is aiming to fill the niches outside of the commodity realm.

One never expects new entrants to a mature business to be welcomed with open arms – at least not from the existing players. After all, new entities tend to shake things up with new ideas, different marketing and sometimes new technology, and that makes competitors comfortable with the status quo a little uneasy.

Justifiably so, but new competition can spark a wave of innovation that pushes the whole industry forward, which typically bodes well for the future.

However, when a new entrant comes on to the scene, as Keystone has done, with nothing new or particularly different to offer – and with the benefit of public support – the knives really come out.

It would seem the existing industry was prepared to let Keystone sink or swim – likely sink – when it was entering the Manitoba scene with an export focus. But now that it has delayed that plan and entered into the domestic business on an interim basis, existing players are hopping mad that it has received so much as a penny from the Manitoba Cattle Enhancement Council.

The MCEC collects voluntary checkoff funds from producers who are matched dollar for dollar by the provincial government during its first three years. It holds the mortgage on the Marion St. property, an investment that can be converted to preferred shares. There is also a clause in the deal that allows those shares to be converted to hook space for MCEC supporters in the event of another BSE-type of market disruption.

“As provincial processors who have had no access to the checkoff funding unless it was to upgrade our already running business to federal inspection levels, we find it abhorrent that the provincial government has allowed the MCEC to approve and fund a plan in which a startup company will compete directly in a local market with provincial slaughter and processing facilities,” a letter to the province from the Manitoba Meat Processors Association says.

“We have done the work that was asked of us in administering the checkoff program and collecting the funds for the MCEC and are shocked that they are spending it on starting a provincial plant that may put self-standing local business out of work,” the letter says.

The letter goes on to acknowledge that there is a need for federal processing capacity in Manitoba. But the Manitoba Meat Processors Association remains opposed to cattle checkoff funds being used to support such a risky venture.

So despite the optimism oozing from the participants of this latest attempt to bring export beef-processing capacity back to Manitoba, Keystone has entered the business knowing there are many who would like to see it fail. Some are even speculating whether it will be weeks or months.

It isn’t big enough. It lacks sufficient capital. It can’t or won’t pay the going rate for cattle. The labour costs here are too high relative to the U. S. (where plants have been repeatedly raided and chastised for using illegal immigrants)

They might be right. They might be wrong.

Either way, the question remains – does what we have today in Manitoba work?

Do producers here sleep easy knowing that their market access can be cut off by one sick animal or a politician’s whim? Are they comfortable with the cost of transporting cattle long distances to slaughter? And even if they can live with those costs, will society forever remain tolerant of the practice from an animal welfare perspective?

If the answer to any of the above questions is no, then what is the industry in this province going to do about it?

The failure of Ranchers Choice suggests that working together through a co-operative model isn’t an option.

We can’t blame the existing provincial plants for being a little miffed that the rules for accessing the MCEC funds were changed in Keystone’s case. But that change also sets a precedent that conceivably works in their favour should they choose to expand or upgrade their businesses.

The clear path forward for the sector here in Manitoba is the establishment of at least one plant that has export certification. Where the waters get muddied however, is finding a business model that works.

The option is to try and possibly fail, or not try at all. [email protected]