One of the perks of writing a column about agriculture in a major city daily is the feedback one gets from urban folks about farming issues.

The level and intensity of interest is surprising at times. For instance, a column last summer outlining the gist and possible implications of the proposed federal support package for the struggling hog sector resulted in more than a dozen written and telephoned responses, which is relatively high for a business column on a complicated subject.

The thing is, only a couple of those responses had anything to do with the subject of the column. The rest, mostly outrage, were focused on the photo the newspaper chose to accompany it: sows and piglets in farrowing crates.

Read Also

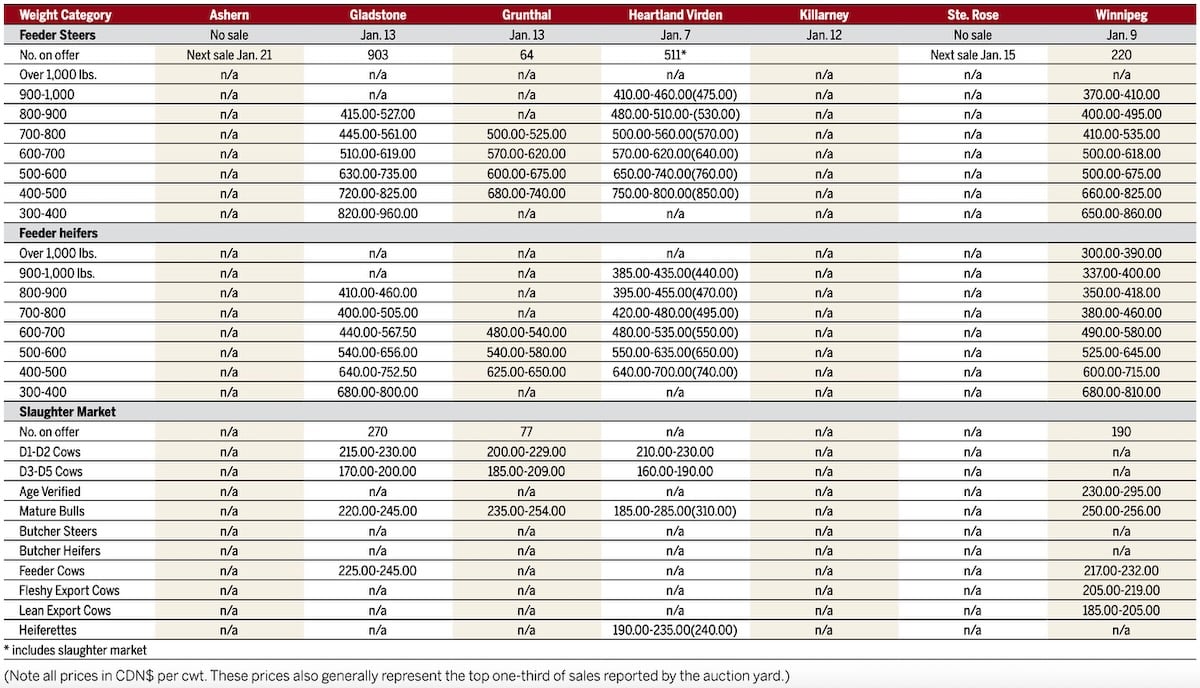

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 15

Trying to explain that these were farrowing crates designed to protect piglets from being crushed and not gestation stalls in which breeding sows spend most of their productive lives, did little to change these individuals’ perception that pigs are not treated very well in modern production systems.

But the fact that several were inquiring as to where they could purchase pork raised using alternative production methods strongly implies these were people who want to continue eating pork – rather than activists trying to end all consumption of meat.

This came to mind last week as nearly 300 people – standing room only – crammed into the lecture theatre at the University of Manitoba for a seminar on the ethics of sow stalls. The interest in this panel discussion on ethics, perceptions and animal welfare of sow stalls hosted by the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics, surprised even the organizers.

It is a very agricultural issue, yet the audience consisted largely of non-farmers. And while you could quibble with the panelists’ representation of the facts in this issue on all sides, there was enough truth in what they were saying to provide a fair reflection of the different perspectives.

The panelists, who included animal welfare advocates, an animal scientist and the province’s chief veterinarian, disagreed on the extent to which sows’ welfare is compromised. For example, the contention that the stalls prevent sows from turning around was countered by scientific studies that show sows don’t have a compelling desire or need to turn around.

Some conclude sow stalls are humane, citing studies which measure tangible things such as a sow’s physical health, her freedom from aggressive herd mates, the ability to tailor her feed to her nutritional needs and her productive performance. The argument goes that as there is no way to prove scientifically that the sow is suffering, it would be wrong to deny producers access to what has proven to be an efficient production aid.

Others disagree, pointing to evidence of behavourial distress, high culling rates due to leg conditions caused by their lack of movement, and their inability to interact as social creatures.

But in the end, all acknowledged the practice of keeping sows in 2×7-foot stalls for most of their lives is on the way out.

In other words, it is not that speakers agreed that sow stalls should be phased out, only that, in all likelihood, they will be phased out. The only “debate” on that point lies within the minds of the people continuing to use them and the people making them.

Granted, most producers are hardly in a financial position right now to make changes to their production setup, even if they wanted to. But whether they are planning to mothball a barn for three years under the transition program or hoping to refinance and continue to operate, they need to keep this in mind.

At last count, seven U. S. states have legislated an end to sow gestation stalls. The European Union will ban gestation crates by 2013. Several major food corporations, as well as processors, have indicated they will move their purchases away from production systems that continue to use them.

If U. S. farmers are required, either by state law or their buyers, to retrofit their barns and change their management practices, is it likely they will tolerate competitive imports from producers who aren’t held to the same standard?

Even if they are required to accept those imports through trade treaties such as NAFTA, the fact that Canadian products are now labelled as such, puts discriminatory advertising within easy reach.

Science may not be able to prove that sows are suffering in gestation stalls, but the emerging science on alternative sow housing systems is pretty consistent. Sows housed in groups require a higher standard of animal husbandry, but there are management options that can result in equivalent productivity and lower culling rates due to leg problems.

Production costs may actually be lower in these systems. Meanwhile, surveys on both sides of the border suggest the customers would be happier. That makes for a pretty strong business case. [email protected]