Bernie Peet is president of Pork Chain Consulting Ltd. of Lacombe, Alberta, and editor of Western Hog Journal. His columns will run every second week in the Manitoba Co-operator. about two to four and embryo survival by about 10 to 20 per cent, Kemp says.

First-litter sows are especially vulnerable, due to their restricted feed intake capacity, he notes. The so-called “second- litter syndrome,” where litter size is reduced in parity two, typically results in lower litter sizes in subsequent parities and culling one parity earlier compared to sows showing increased litter size in parity two.

Read Also

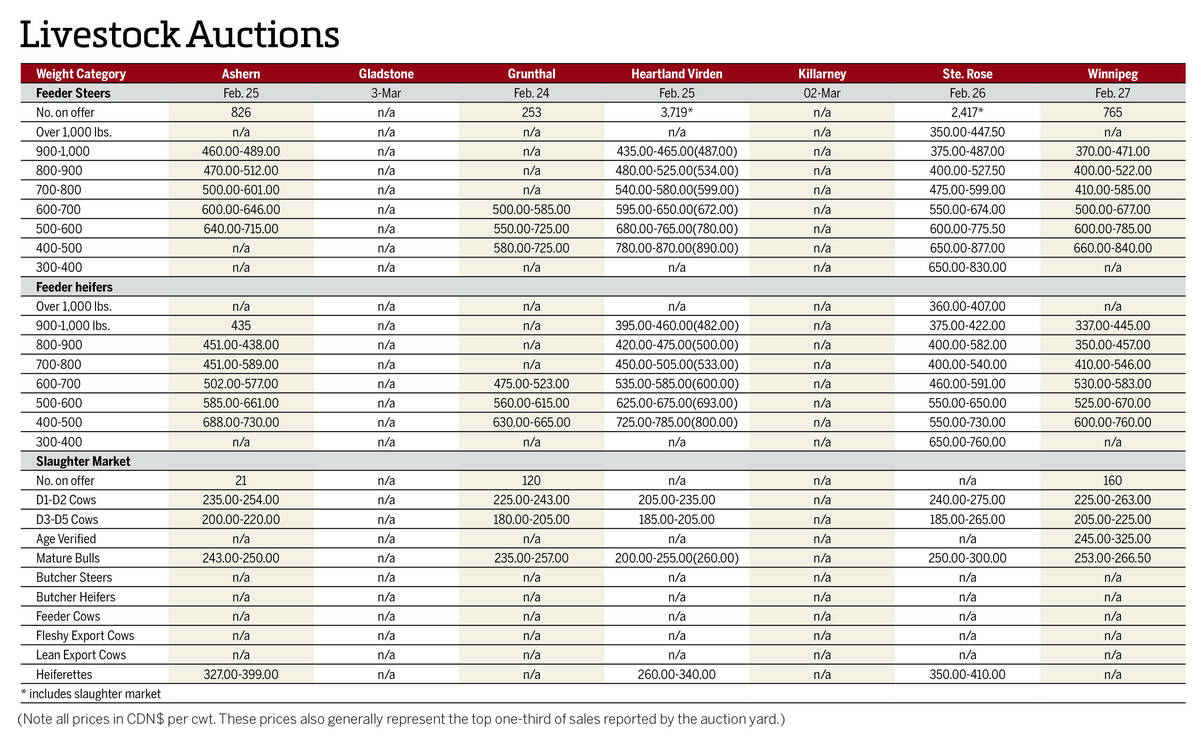

Manitoba cattle prices, March 4

Chart of weekly Manitoba cattle prices.

OPTIMIZING POST-WEANING PERFORMANCE

Gilt development and age/ weight at first mating have a large effect on lifetime productivity, Kemp said. “Although mating gilts at a young age or a relatively low body weight may not have negative consequences for first-litter size, second-litter size may still be compromised since young sows have the desire to grow and feed intake capacity is limited during first lactation,” he points out.

“Experimental data from our research group indicate that sows with a low body weight after first lactation – less than 150 kg– have a reduced secondlitter size.” He notes that current advice is to inseminate gilts at 240 to 260 days, although he questions whether this is always economically justified.

Kemp stresses that, especially for gilts, excessive feed intake during gestation decreases voluntary feed intake during lactation. “Gilts should be fed according to their requirements for maintenance, reproduction and growth but not be overfed,” he advises.

A number of factors that influence lactation feed intake need to be considered because maximizing feed intake will result in improved subsequent reproductive performance. Of these, room temperature is one of the most critical, Kemp suggests. “In the temperature range of 25-27 C, voluntary

feed intake decreases by 214 g per C,” he explains. “Skin wetting, drip cooling and snout coolers will increase lactation feed intake of sows at high ambient temperatures.”

Intake can be increased by feeding sows more than twice a day and feeding ad lib has been shown to increase feed intake by 10 per cent. However, he cautions producers using ad lib feeding to remove feed from the trough once daily to prevent deterioration and mould development.

Lactating sows have a very high water requirement and there is a close relationship between water intake and growth and mortality in piglets, Kemp said. “It is advised to supply water ad libitum during lactation and to regularly check the water output of nipple drinkers, which should be two to four litres per minute.”

Another approach to relieve the sow from the burden of lactation is through reduction of the suckling stimulus. “Management techniques like removing the whole litter for part of the day or split weaning, where part of the litter is removed a few days before

weaning, can be successful but a drawback of the use of these techniques can be the occurrence of oestrus prior to weaning,” Kemp said.

POST-WEANING MANAGEMENT

Al though lactat ion feed intake has the biggest impact on subsequent reproductive performance, there are a number of management techniques that can be used after weaning to “repair” the damage caused by inadequate intake, he said. “Ad lib feeding after weaning has been shown to increase the percentage of sows in oestrus within seven days after weaning to 62 per cent as compared to 52 per cent for restricted feeding,” he said.

“The use of PG600 directly after weaning results in an improvement of the weaning to oest rus interval in many studies but sometimes it results in lower pregnancy rate or lower litter sizes,” Kemp continues. “This may be related to differences in follicle development at time of PG600 injection.”

Ovulation rate and embryo survival may be improved by allowing the first parity sow to recover for a longer period after lactation, Kemp suggests. “One way to do this is to treat sows with altrenogest (Matrix or Regumate TM) for three to seven days after weaning to artificially extend the weaning- to-oestrus interval,” he says. “In research trials, this resulted in an increase in pregnancy rate of 5.6 to 15.7 per cent and an increase in subsequent litter size of about 0.2 -0.8 piglets.”

After weaning, sows need to restore body reserves that were lost during lactation, however often feed levels are too low in practice, Kemp said. “Recently, we studied the effects of feeding 2.5 or 3.25 kg per day from day three to 32 of pregnancy on litter size and farrowing rate,” he explains. “The high feeding level increased total born and live born piglets by 2.1 and 1.8 piglets, respectively. Piglet weights were similar at both feeding levels.” However, he notes, farrowing rate was lower for the sows fed at the higher level.

———

“Althoughmatinggiltsatayoungageorarelativelylowbodyweightmaynothavenegativeconsequencesforfirst-littersize,second-littersizemaystillbecompromised.”

– DR. BAS KEMP