A small-scale study of hog barn workers in North Carolina found nearly half carry livestock-associated bacteria in their noses, and that this potentially harmful bacteria remained with them up to four days after exposure.

Researchers with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health tested 22 workers over a period of two weeks during the summer of 2012 and found 19 carried at least one type of Staphylococcus aureus at some point during the study period, while 16 of them (73 per cent) carried the livestock-associated strain. In contrast, only about one-third of the general population carry a strain of Staphylococcus aureus associated with humans.

Read Also

Beef sector seeks higher AgriStability cap

Facing unpredictable market conditions and rising expenses, Manitoba cattle producers would like to see an increased AgriStability cap.

Much of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria the workers carried were antibiotic resistant.

Researchers said they were surprised by the persistence of the bacteria, which heightens the possibility of workers spreading it to others.

“Before this study, we didn’t know much about the persistence of livestock-associated strains among workers in the United States whose primary full-time jobs involve working inside large industrial hog-confinement facilities,” said study author Christopher D. Heaney, PhD, MS, an assistant professor in the departments of environmental health sciences and epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in a release. “Now we need to better understand not only how persistence of this drug-resistant bacteria may impact the health of the workers themselves, but whether there are broader public health implications.”

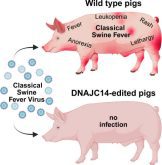

European limits

The researches noted that in Europe, the children of livestock workers have been diagnosed with a livestock-associated strain of MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) that doesn’t match the more widely found community- or hospital-associated strains.

Staph are common bacteria that can live in human bodies without consequence. When they do cause infection, most aren’t life threatening and appear as mild infections on the skin, like sores or boils. But staph can also cause more serious skin infections or infect surgical wounds, the bloodstream, the lungs or the urinary tract. Strains of staph like MRSA, which are resistant to some antibiotics, can be the most damaging because they can be very hard to treat.

MRSA is particularly dangerous in hospitals where the bacteria are hard to get rid of and the people there are the most vulnerable.

How does it spread?

Heaney and the team are doing more research to see whether hog workers with persistent drug-resistant bacteria are spreading it to their family members and communities.

“We’re trying to figure out if this is mainly a workplace hazard associated with hog farming or if it is a threat to public health at large,” he says. “To do that we need to learn more not just about how long workers carry bacteria in their noses, but how it relates to the risk of infection and other health outcomes in workers, their families, and communities.”