Ergot is increasingly creeping into cereals in Western Canada, as well as into cattle feed.

If grain has been contaminated by the fungus, it will be refused for human consumption and sent to the livestock industry.

Darby Meyer, a graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan, has been continuing research into the use of ergot-affected grain for feedlot cattle.

Read Also

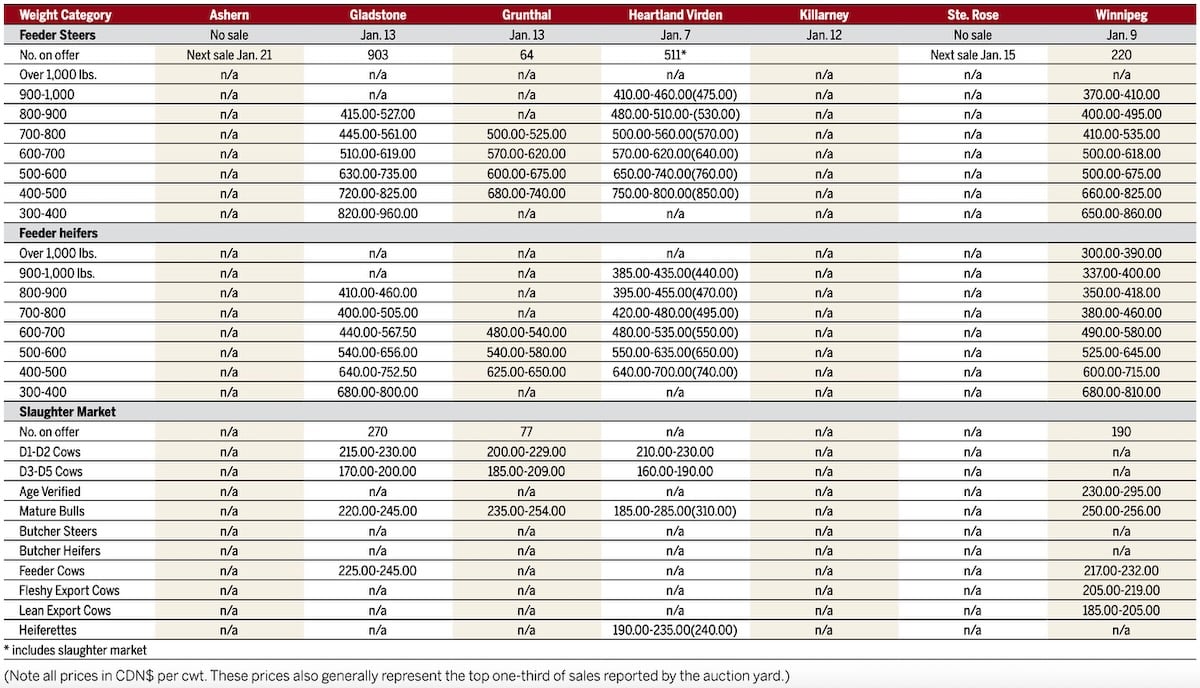

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 20

“The first study we finished up in March of 2025,” she told a recent field day at the University of Saskatchewan’s Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence.

“It was looking at the impact of feeding ergot alkaloids at two parts per million, with and without the binder, to finishing feedlot cattle in the winter.”

WHY IT MATTERS: Mycotoxins can be a hidden threat cutting into cattle operations through their herd’s feed ration.

The binder is a mycotoxin deactivator from the Austrian company DSM, which is mixed with the grain to reduce the toxicity of the fungus Claviceps purpurea, wich causes ergot.

Mycotoxins are a secondary metabolite, meaning they help the fungus to continue to function. By deactivating them, the ergot can be more easily consumed and reduce effects on the animal consuming the affected grain.

The effects are important to address because they can cause serious harm. Common symptoms of ingesting ergot include vasoconstriction and the tightening of blood vessels, gangrene resulting in the loss of ears, tails and hoofs, and impaired ability to thermoregulate.

For the studies, cattle are monitored daily to ensure their health and well-being. As well, heat stress mitigation options have been added, such as extra water troughs and shade access.

The first study was not just on the impact of feeding ergot, but also on winter finishing instead of summer. That study comprised 180 steers in 12 pens with three feeding treatments: a control, ergot and ergot-binder mix.

It was a 126 day finishing period, and every three weeks steers were weighed and had lameness scores, hair coat scores and hair shedding scores recorded. On the first, middle and last day of the finishing period, blood samples, rectal temperatures, flight speeds and infrared thermal images were also recorded.

When processed, carcass quality parameters and yields were collected, and livers scored for abscesses.

“The results we saw from that study showed that the mycotoxin binder was effective for the first half of the study,” Meyer said.

“So the steers that were fed the ergot and the binder had similar average daily gains to the control animals, and then the animals that were fed just ergot had lower average daily gains than those animals.”

During the second half of the finishing period, the results flipped. Those fed ergot and binder had similar average daily gain to the ergot-only animals, and the control had higher average daily gain.

“What we did see was about a five per cent reduction in dry matter intake and also average daily gains,” she said about the last 63 days of the study.

“But the gain-to-feed ratio for all the treatments were very similar.”

Interestingly, a previous student’s study on the topic of ergot consumption saw a 10 per cent decrease in average daily gain and dry matter intake. That study had included 60 individually housed cattle in a feedlot, which were all fed the same ergot blend.

Meyer’s research has continued into the summer with a second round of animals for a summer finishing study.

Currently, there are 360 steers sorted into 24 pens at the centre for the trial, which started this January. The steers underwent a 21-day transition phase to slowly adjust from a high silage to a high grain diet.

The trial has expanded with six treatments: a control, control with binder, continuously fed ergot, continuously fed ergot-binder mix, intermittently fed ergot and intermittently fed ergot binder.

Each ergot diet is being fed at two parts per million.

“We thought it was important to have the intermittent treatments,” she said.

“Because in an actual feedlot setting, not necessarily every load of grain that the feedlot gets is going to be contaminated with ergot. So we thought it was important to be able to evaluate feeding it intermittently and compare it with our continuously fed control groups.”

For this study, there is the additional inclusion of feed intake measurements using the GrowSafe electronic feed bunk system. It takes measurements of feed by weight when filled and measures animal feed intake by how much feed disappears when the steer enters the bunk.

Individual intake is noted by a GrowSafe radio frequency identification tag in each animal’s ear.

At the end of April, the steers were re-randomized and began the finishing period.

With the randomization, a bit of each feed treatment was in each pen, and Meyers said that part of the study will be analyzing the various combinations. She expects there will be varying average daily gains due to the combinations and the effects of the treatments during the backgrounding stage.

It’s now near the halfway point of finishing, and the same tests as the winter finishing study will soon be underway.

Results are still to come, and they will be compared to the winter study to see if there are any additional differences.