Canada’s broiler chicken industry has reached a new quota allocation agreement, avoiding a potential showdown with a federal regulator that could have thrown the system into chaos.

The Farm Products Council of Canada had threatened not to approve Chicken Farmers of Canada’s allocation requests unless it came up with an agreement reflecting provinces’ comparative advantages for growing chicken, officials said.

If the council had rejected CFC’s allocations, the industry could have lost a main pillar of supply management: the ability to match supply with market demand.

Lacking that ability could have produced a production free-for-all among provinces, returning the industry to the interprovincial chicken wars of the 1960s and 1970s which led to the creation of supply management in the first place.

Pushed

The council’s threat helped push CFC past the dickering of recent years towards the new allocation agreement, said Jake Wiebe, Manitoba Chicken Producers chairman.

“We certainly felt we were on the edge of the precipice,” said Wiebe.

“The fact that we were standing on the edge of the precipice had us saying, how much is supply management worth to us?”

Wiebe said Laurent Pellerin, who chairs the Farm Products Council of Canada, had given CFC deadlines for reaching a new agreement, although he kept extending them.

“But he said if there isn’t a comparative advantage (component), Farm Products Canada will not approve our allocations.”

Dave Janzen, Chicken Farmers of Canada chairman, said he was feeling heat from Pellerin to reach a deal or risk imploding the system.

“He was putting a lot of pressure on me and using it as a motivator for me to keep working with the provinces,” said Janzen, who farms at Abbotsford, B.C.

Read Also

Cabbage seed pod weevil the surprise top canola pest in Manitoba for 2025

Get set to scout this summer. After a few years of low profile in Manitoba, cabbage seed pod weevil populations, among a few other pests, boomed here in 2025.

“There was tremendous risk on us not coming to any agreement.”

CFC announced last week all 10 provincial chicken-marketing boards had signed a memorandum of understanding which partially bases allocations for each of the eight-week rolling production periods on factors reflecting provinces’ comparative advantage.

The result is something called “differential growth” in which some provinces get proportionately more chicken than others, depending on economic conditions.

New formula

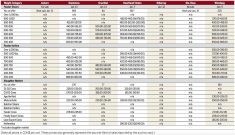

A complicated formula bases 45 per cent of future chicken market growth on “pro rata” (historical market share) and 55 per cent on comparative advantages, including population growth, cost of living, farm input prices and other factors.

The main benefactors are Alberta and Ontario, two of Canada’s major chicken producers. At the same time, some provinces, including Manitoba, will give up part of their projected future growth so Alberta and Ontario can have more.

Wiebe said, in his own case, that’ll cost him 80 birds per cycle, based on future estimated growth. Wiebe and his family currently grow 60,000 kg of chicken per cycle on their farm near New Bothwell.

But Wiebe said the loss is worthwhile in order to preserve the system. Manitoba was one of the leaders in proposing the new allocation formula.

“We’ve really rallied with (other smaller) provinces and said, sure, some of this isn’t exactly what we’d like. We’d like to be growing faster. But the reality is, we’re also the ones who’ll be hurt the most if supply management goes.”

Alberta withdrew from CFC last year over repeated failure to achieve differential growth, despite its rapidly growing population. Now it will return to the fold.

The agreement announced Nov. 20 still has a way to go before it is formalized. Federal Agriculture Minister Gerry Ritz and all 10 provincial regulatory boards must sign off on it and the Farm Products Council has to review it. Once approved, it becomes an amendment to the federal-provincial chicken agreement. CFC hopes everything will be settled by mid-2015.

Other issues

Meanwhile, CFC is proceeding as if the agreement were already finalized, Janzen said.

Provinces have been arguing over differential growth for six years. Now that the issue is finally settled, the chicken industry can turn its attention to other pressing matters, said Janzen.

The main one is a trade dispute with the United States over spent fowl imports. Canada alleges U.S. processors fraudulently label fresh chicken as spent fowl, which is not subject to import controls. It is then resold in Canada as fresh.

CFC says over 100 million kg of the product enters Canada annually this way, bypassing tariffs designed to limit imports and protect supply management. This displaces over 10 per cent of Canadian chicken production and affects CFC’s ability to allocate.