Compared to last year’s drought-driven berry bust, this summer has been a great turnaround for berry pickers. Across the province, people are filling pails with these tasty, versatile wild delights.

I’ve been a berry picker ever since childhood. These days, picking berries not only fills the larder, but helps to connect me to my family history, as well as the history of this region.

My mom told stories about berry picking when our extended family-built cottages in the Whiteshell in the 1950s. In the first year, they found the mother lode of blueberries that could not be ignored. Hammers were put down and the babe in arms – me – was placed in a netting-draped bassinette among the berry bushes as Mom, Dad and the aunts and uncles filled their baskets.

Read Also

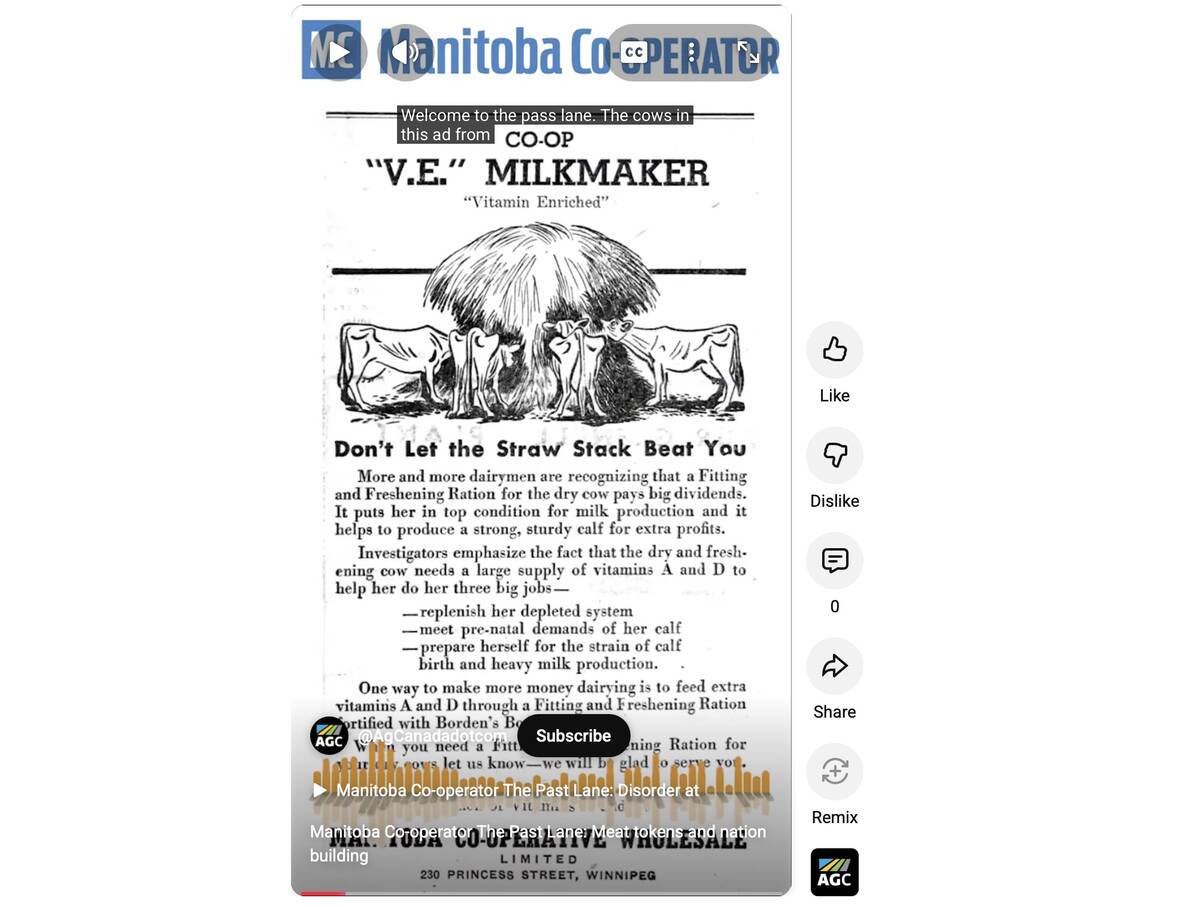

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

As a kid, I was conscripted in the family berry-picking army. I can’t say that I enjoyed it, but that swim in the lake after we got back, sweat-stained and bug-bitten, was a little bit of heaven.

Decades later, those early experiences have become hard-wired, and I am driven to put down a variety of berries for pies, jams and sauces.

The year kicks in with saskatoons, then quickly slides to blueberries. Later in August, chokecherries require attention. Over the years, I have also picked wild strawberries, raspberries, high-bush cranberries and even hawthorns. In northern Manitoba, I have also enjoyed cloudberries, a golden, raspberry-like delicacy, and mossberries, a local name for bog cranberries that have been a staple for northern Indigenous people.

This year the late spring seemed to push everything back by at least a week. Perhaps because the bushes were still recovering from last year’s drought, saskatoon picking in my area was only so-so. However, some extended walks helped to locate a few hot patches that will meet our needs for saskatoon pies and saskatoon/apple crisp.

Last year’s drought was so severe it killed some blueberry patches on drier sites in areas of the Whiteshell where I pick. After a bit of scouting, I found a few sweet spots where the damp spring and summer made for fantastic picking. It took only a few morning sessions to meet our annual needs for pies and other baking.

My wife, Linda, makes some of the best pie crusts I have ever eaten. How she turns five ingredients into a crust that makes a blueberry pie pure ambrosia is nothing short of alchemy in my books.

As I write, in mid-August, I expect that chokecherries will be just about right in two or three weeks’ time, and we will put that into syrup, a wonderful addition to pancakes and waffles.

All of the common berries are critical foods for our black bears. A poor berry year means skinnier bears, reduced winter survival and fewer cubs born the next spring.

I am always amazed by the fact that one of the largest wild critters in these parts get that way mainly by eating ants and berries. Though I have rarely seen bears while picking, I see that they have often beaten me to good spots. They can give a patch a sound beating, but they are on a mission, and niceties don’t enter into it.

Looking at Indigenous history in our area, berry picking was serious business, contributing a key component to annual diets. Pemmican, a concoction of dried berries (saskatoons in these parts), animal fat, and dried, shredded bison meat, was a crucial food to tide folks over meagre times. This “super food” didn’t spoil and was high in protein, energy and a host of vitamins and micronutrients from the berries. In addition to their functional value, berries would have been one of the few sweet foods available.

Pemmican also played a major role in the fur trade. In addition to animal pelts, there was a major trade for pemmican, as it was a staple food for voyageurs, the swarthy canoe-paddlers and pack-haulers who were the transportation engines in the trade. In the days before fossil fuels, land-based fuel and especially pemmican drove the fur trade.

I’m sure that Indigenous kids were conscripted to pick berries just like I was, but they would have had a fundamental need and sense of purpose. However, like me, they would have sneaked a few mouthfuls when Mom wasn’t looking, just because they tasted so darn good.

European settlers would have learned much from Indigenous people about how natural foods could supplement meagre diets, and berries would have been high on the list of opportunities. Later-arriving setters might have had the added opportunity to can berries for the long winter to come.

Back in the 1970s, I spent two summers working on a wildlife research study in the northern Interlake. Many farms were only a few decades from their establishment as homesteads. Families with mixed farms still had chicken coops, a few hogs, large gardens and the means to put down produce as part of the annual food cycle. Berries could be a big deal, I was to learn.

One summer day I met two farm women picking saskatoons. I casually asked how they would use the berries.

“I like to can them so we have berries through the winter,” one lady replied. I then asked how many they were going to put down. “Three hundred jars,” was the answer. Any time I get a little cocky about the berries accumulating in my freezer, I think about them.

Out in the berry patch, as the flies swirl around, the minutes become hours, and my pail slowly fills with nature’s bounty, I can’t claim to having many profound thoughts.

“Gee, that’s a nice bush,” may be about as deep as it gets most often. My berry picking is recreation in the truest sense of the word: it re-creates an activity that had a greater purpose in earlier times. I love eating the results, but the connection to the land and to people over time also helps me to push away from the breakfast table, pick up the pail and make my way to the berry patch.