Minimal snow cover, frigid temperatures in mid-January and above-average temperatures after that may have set the stage for winterkill in winter crops.

The risk is high enough to cause concern among crop specialists.

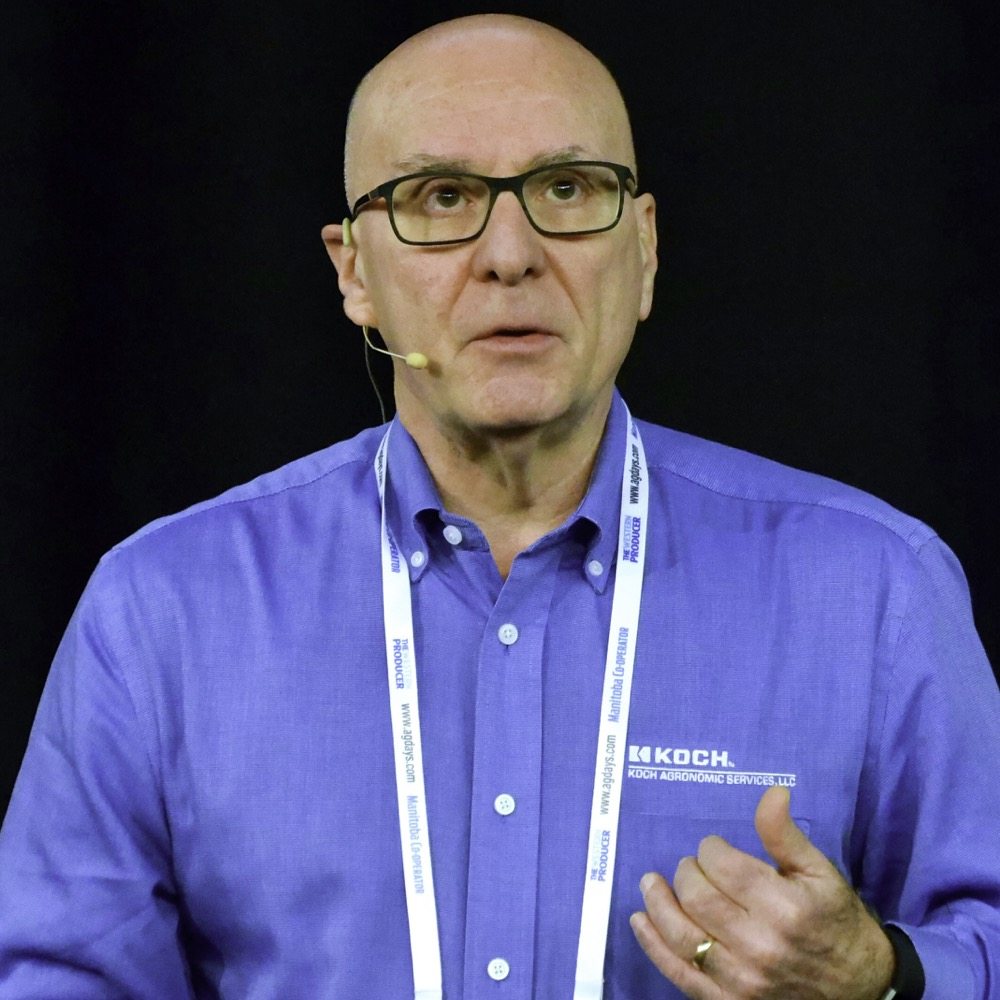

“The eastern Prairies are in a little bit better shape than (Saskatchewan and Alberta) but there’s huge swaths that in my mind are critically low in terms of snow cover and those types of conditions that enhance winter survival,” said Brian Beres with the AAFC Lethbridge Research and Development Centre.

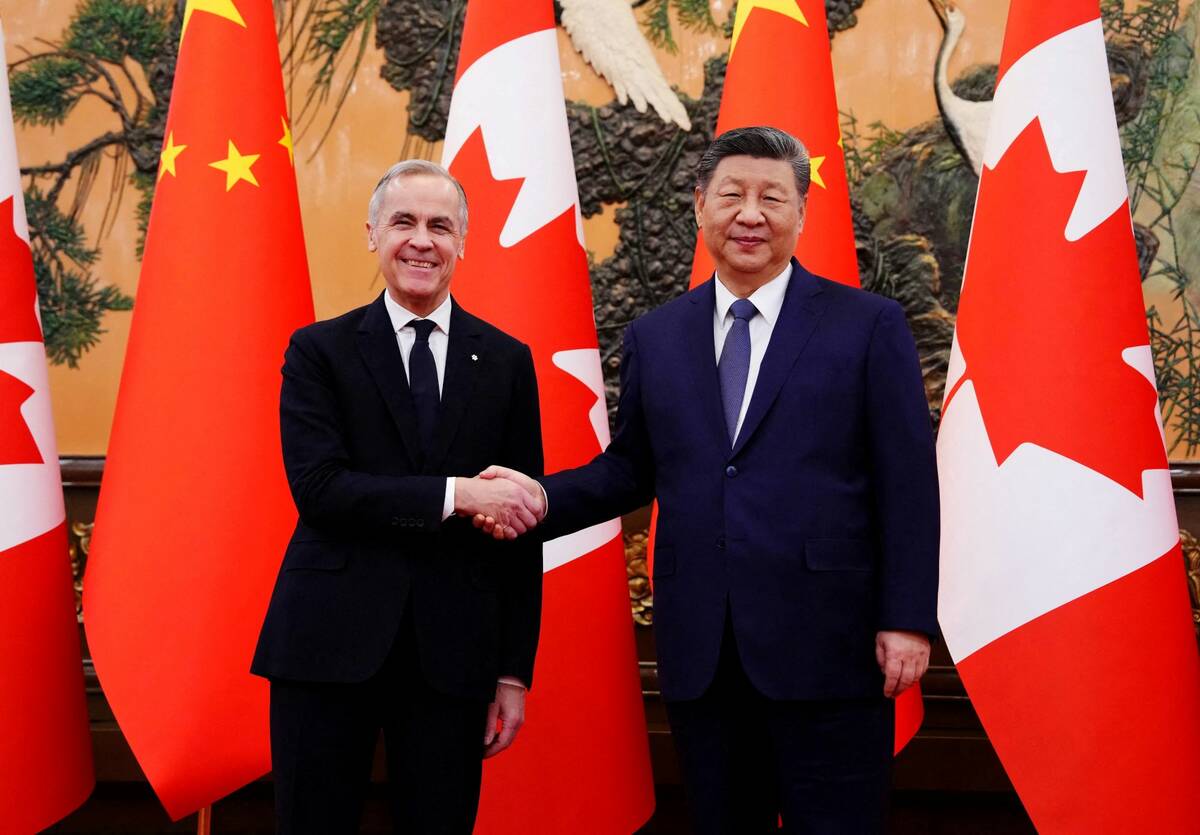

Read Also

Market impacts of canola headlines need digesting

January 2026 has been quite the month for Canadian canola trade, how will it all ripple out in the market?

Further complicating matters is the mid-January deep freeze that saw some Prairie regions experience wind chill lows of -55 C.

“Hopefully that cold spell wasn’t so long to the point where it caused (winterkill) and hopefully the conditions before that — with those abnormally high temperatures — didn’t trigger some sort of dehardening process within the plants. But if I was a farmer, I would be out taking a look,” he said.

Anne Kirk, cereal crop specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, expressed similar concerns for her province.

“The warm temperatures have been melting what snow cover there is and many fields in central Manitoba have very little remaining snow,” she wrote in an email. “If there is a lack of snow cover and temperatures drop, then I would be concerned for the winter cereal crops.”

An up-and-down winter combined with little snow cover could set the stage for winterkill problems in fall-seeded crops.

Obviously there’s no remedy for winterkill: a dead plant is a dead plant. However, a small amount of winterkill in winter wheat will not necessarily make the remaining crop unsaleable, said Beres.

“The nice part about winter wheat is you’ve got a lot of end-use market flexibility. And because it’s winter wheat, you can make a lot of decisions in that spring window and still get some cash generated from that parcel of land.”

A number of conditions contribute to winterkill, including heavier clay soils, late planting, loose soil at planting, inconsistent snow cover, drainage issues and severe freeze-thaw cycles.

The warm weather-pooling-freezing cycle throughout the Prairies this winter looms large in the minds of Beres and Kirk.

“A … concern with this warmer weather is water pooling and freezing in low areas of the field,” wrote Kirk. “Winter cereal crops are respirating even when dormant, and standing water or ice cover restricts gas exchange in the crop.

“Because the plants are dormant, they are more likely to survive prolonged periods of stress, but prolonged standing water or ice cover is detrimental for winter crops.”

The tendency of water to pool in low spots highlights the importance of scouting those areas in spring, said Beres.

“If you see those low spots of winterkill in your field, that’s probably a good indication that there was some of that going on in your field and the low spots obviously are going to melt and have some pooling before anywhere else.”

Winterkill potential can be reduced through use of winter-hardy varieties, said Beres, but those aren’t entirely immune.

“If you get 10 days of warm temperatures and then get hit with an abnormal cold spell like we did, now the plant’s potentially dehardened.”

Dehardening occurs when plants lose their acquired cold tolerance in response to warm temperatures.

Spring scouting can help producers measure the effects of winterkill and the overall health of a winter crop. However, initial assessments can be deceptive in the case of winter wheat because a good crop can be grown in spite of winterkill.

“Often you’ll go and monitor your fields and think you’ve got a bigger problem than you do. And then you wait a little longer and all of a sudden, the winter wheat — being the resilient crop that it is — starts to turn it around,” said Beres.

“Get a good idea of what your stand density is, because even if you’re in that range of 10 to 15 plants per square foot, you’re going to produce an acceptable crop just because of winter wheats’ tillering capacity and whatnot. I know guys that have left crops with lower plant stands than that and did OK, so the sky isn’t falling yet and it wouldn’t be until you confirm that you’re maybe at less than seven to eight plants per square foot.”

Some tactics can be employed in spring to minimize the impact of winterkill, said Beres. One of them is overseeding.

“If you’ve got a field that’s got big pockets that have been wiped out, you can go in and overseed with spring wheat in some of those situations and then hope that the two sync together.”

Don’t overdo it if there are only small pockets of winterkill, he added.

“Some guys overseed the whole (field) and then they’re in a feed wheat situation because it’s not like you’re going to be selling it off as anything other than that.”

Kirk also recommended spring plant counts in various parts of the field.

“Weed management, early application of nitrogen to encourage tillering and increasing disease scouting are important for the remaining winter crop,” she wrote. “If the crop is patchy, prior weed control is especially important as there would be patches of the field providing very little weed competition.”

Depending on severity of the damage, producers may choose to reseed the field with a spring crop, she wrote.

“In some cases farmers may just replant, with a spring crop, patches of the field or may kill the remaining winter wheat crop and replant the entire field.”

The Winter Crop Survival Model takes crown depth (one inch) soil temperatures under winter cereals from sensors throughout Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“This model compares the cold tolerance of winter cereal varieties to daily average soil temperatures at crown depth,” Kirk wrote. “These graphs identify winterkill days based on their model and give an early indication if there is a concern for winter injury or winterkill.”