Fusarium head blight continues to be a major challenge for Manitoba farmers, but there’s emerging evidence that they may be able to manage around the worst of it.

At the recent Manitoba Agronomists Conference in Winnipeg, Dr. Anita Brûlé-Babel of the department of plant sciences at the University of Manitoba shared a number of management practices that producers can employ to manage the risk of FHB infection.

FHB management is complex and producers need to use all the tools they have available to them. “Variety resistance is not complete and producers need to pay attention to what is going on environmentally, but with resistance and these other management practices they can significantly reduce their risk of FHB,” said Brûlé-Babel .

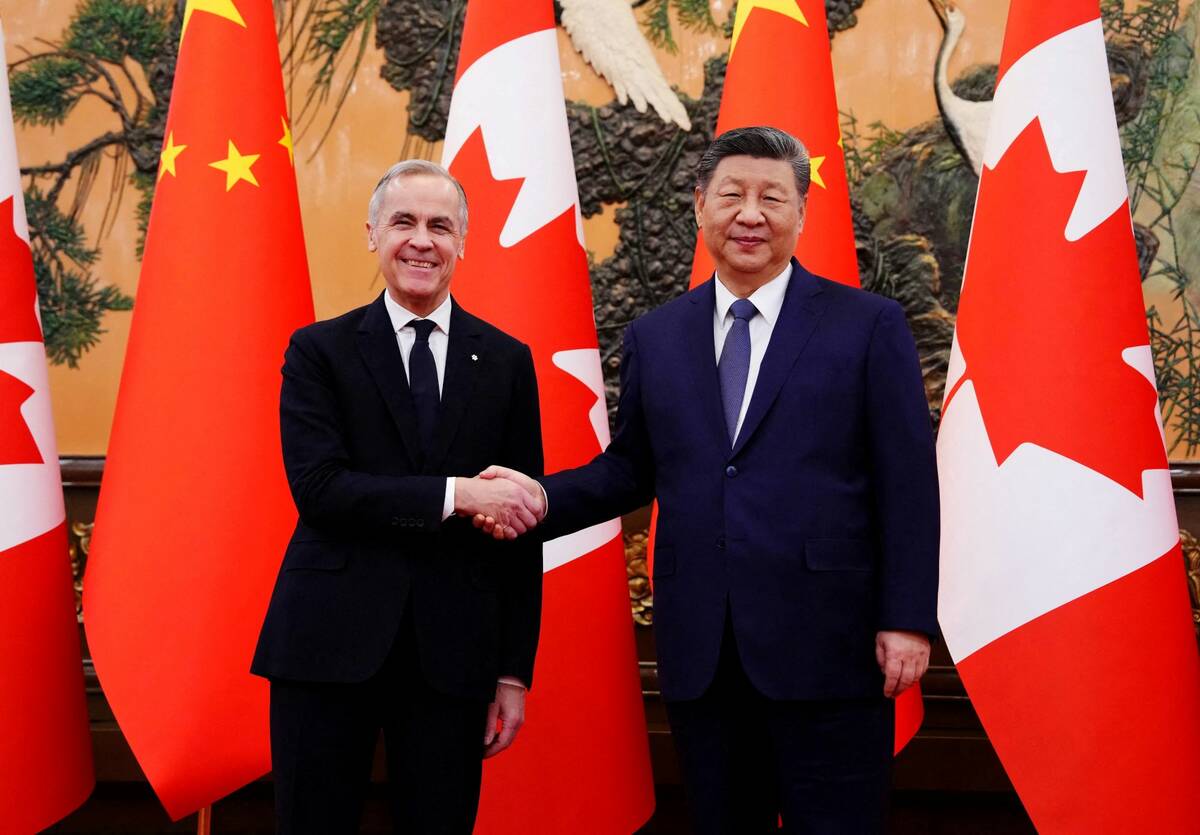

Read Also

Market impacts of canola headlines need digesting

January 2026 has been quite the month for Canadian canola trade, how will it all ripple out in the market?

There are different types of fusarium that can infect wheat crops, but the most common species in Manitoba is Fusarium graminearum. FHB requires the presence of the pathogen, a susceptible host and the right environment to develop.

The pathogen needs warm, moist conditions, so risk is highest following significant precipitation events and when daytime temperatures are around 16 C to 32 C and nighttime temperatures are above 10 C. Wheat is most susceptible at the flowering stage, but infection can occur up to the soft-dough stage, and may not always show symptoms, so if FHB has been prevalent in a particular area, producers in that region may want to test for the presence of DON that could be caused by later infections.

Manitoba producers have seen a number of severe fusarium head blight (FHB) epidemics over the past 15 years, including the summer of 2016, which has negatively affected both yields and end-use quality. Grain infected with FHB can produce deoxynivalenol (DON), a mycotoxin that affects both food and feed safety and reduces grain marketability when growers have significant levels of infection in their crops.

Know the risk

Conditions that increase the risk for FHB can change very quickly, so producers should regularly consult online provincial FHB risk forecast maps.

A traditional way to help reduce FHB infection has been to use practices that promote a uniform stand, with the idea that if there is a high risk of FHB, producers can apply a fungicide and it will be more effective if the crop is all at the same stage of maturity. Conversely, varying planting dates either with the spring wheat crop or mixing winter and spring wheat varieties, so not everything is at the same stage at the same time is another option to spread out the risk.

Resistant varieties

Producers need to know the susceptibility of the wheat variety they are growing. Provincial seed guides list FHB resistance ratings for spring, winter and durum wheat varieties that are moderately resistant, intermediate, moderately susceptible or susceptible. “In high-risk areas producers should choose at least a moderately resistant variety. Even though there may be other factors that are contributing to their decisions such as yield, height and maturity, FHB resistance should be one of the main considerations,” said Brûlé-Babel.

Although FHB resistance ratings are a good first line of defence producers should not assume that using a resistant cultivar is the only management tool needed to control FHB. Other strategies are important to help manage the pathogen, and when combined can help reduce infection by 30 to 50 per cent.

Fungicide timing

Producers can use fungicides to suppress FHB symptoms, but they will not give complete control of the disease. Timing of application during flowering is critical to get the most benefit. Research studies have shown that the best time to spray is after 75 per cent of the heads have emerged from the boot. “If the crop is very uniform it makes the decision about what is the optimum time to spray easier. It’s a very short application window, but we have seen with late infections, and even with applications as late as seven days after the optimum timing, some efficacy with these products,” said Brûlé-Babel. “Research has shown that the best efficacy of fungicides is achieved in combination with resistant varieties.”

How fungicide is applied is another factor in how much it will help to suppress disease. “When spraying for FHB producers are trying to attach the fungicide to a vertical surface — not like weed control where the spray is trying to contact the canopy,” said Brûlé-Babel. “The way that you spray, and the technologies you use to apply the fungicide will also affect the efficacy.”

Healthy seed

FHB-infected seed will affect seedling vigour, plant stands and crop uniformity, so producers should always seek to use as healthy seed as possible to ensure a big, uniform, vigorous stand but using infected seed in itself does not necessarily result in higher levels of FHB disease in the crop.

Crop rotation plays an important role in helping to reduce FHB infection. Fusarium graminearum survives on crop residue of corn, small grain cereals — wheat, barley and oats ‚ and if infected the pathogen will grow on these residues as long as it is there. Avoiding corn/wheat, wheat/wheat and barley/wheat rotations will help disrupt the disease cycle, as will rotating to non-susceptible crops such as oilseeds or pulses. The length of crop rotation will depend on the rate at which crop residues are decomposing — for example corn crop residues take longer to decompose than other cereal residues, and that may affect residue management decisions.

Removing infected crop residue from the field, or using tillage to bury FHB-infected crop residue, will help reduce the level of inoculum, and chopping crop residue into smaller pieces will help it to degrade faster. Brûlé-Babel cautions that under the right conditions FHB spores can travel long distances so good, local management practices will not guarantee there will be no infestation.

Harvest management

The allowable fusarium damaged kernels (FDK) in wheat samples is between 0.25 and four per cent by weight depending on the class and grade. Some producers are using increased combine fan speed or shutter opening at harvest to reduce FDK. Another option is to harvest areas of the field with higher infection levels separately.

Harvested grain should be dry before it goes into storage. “It’s important to note that grain is graded on FDK but it’s sold on DON levels. FDK and DON are not always highly correlated because it may be different fusarium species causing the disease symptoms, or we may have late-season infections that don’t show symptoms of the disease, but still have high levels of DON,” said Brûlé-Babel.